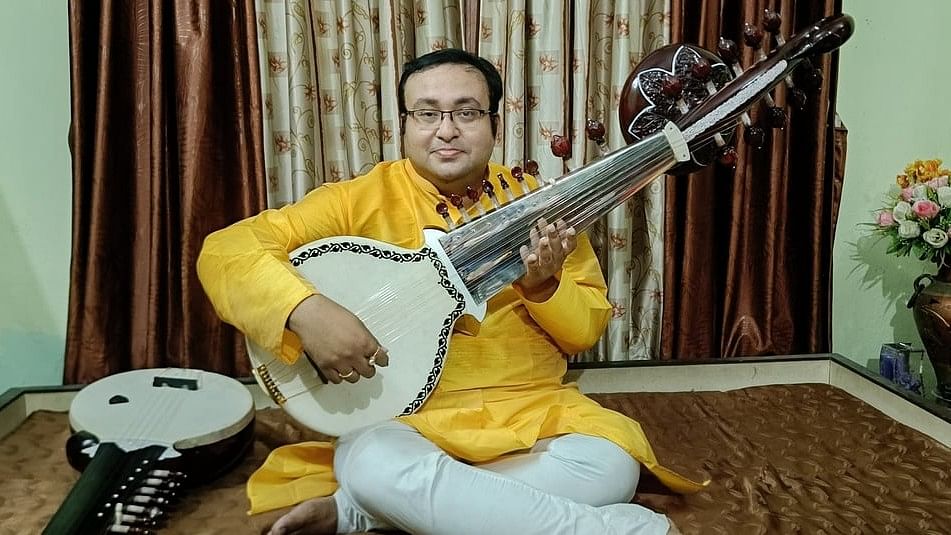

Joydeep Mukherjee with the sur rabab.

I have been playing the sarod for 37 years and I am still a student, learning something new every day. My journey with other stringed instruments is 12 years old.

One day, in 2013 or thereabouts, I was grappling with the traditional instrument sursingar, trying to play an alaap in raga Darbari Kanada. The sursingar is known for its enormous size, and handling it is not easy as it has a string orientation different from other instruments. Noticing me struggling, my guruji Pranab Kumar Naha asked me to try a variant of the sursingar. It is relatively smaller and hence easier to play, but it called for some modification to suit my playing. That was the first time the idea of reviving and modernising an instrument occurred to me. And that is how my journey of reviving ancient musical instruments began.

Most recently I have attempted to revive the age-old Tanseni rabab and sur-rabab. The Tanseni rabab was modified in the 18th century to make the sursingar, and the sur-rabab inspired the creation of the sarod in the 19th century.

I belong to the Shahjehanpur–Bengal gharana of Hindustani music. In our parampara (tradition), we have four types of sursingars. I began training in 1987, when I was just four, under the late Pandit Naha,

a senior disciple of the legendary Pandit Radhika Mohan Maitreya. I continued under him for 37 years, until his passing earlier this year. I also received training in rhythm from the tabla virtuoso Debasish Sarkar. I cannot tell the story of the revival of the Tanseni rabab and the sur-rabab, without first recounting how I brought the sursingar back from the brink.

Long history

In the 16th century, Mian Tansen developed a special rabab, modifying the Afghani rabab. The rabab he created was longer and bigger than the Afghani rabab. It was named Dhrupad rabab or Seni rabab. After Tansen’s death, it became widely known as the Tanseni rabab.

Largely played in north India, the Tanseni rabab had a large hook at the back of its head, making it easier for a musician to sling it over the shoulder and play it even while walking. Nomadic musicians used it widely. However, the Tanseni rabab had a drawback. During the monsoon months, due to the moisture, the tension of the hide at the top of the sound box would give way, and this affected the quality of the sound. Tansen spent his life trying to rectify it, but couldn’t.

In the late 18th century, Jaffar Khan, a descendant of Tansen, was performing on the Seni rabab at the royal court of Benaras in the presence of the Maharaja of Kashi. It was the end of June. The monsoon had just set in. The hide-covered sound box had absorbed the moisture in the air, and so had the strings, made from catgut. This resulted in a dull sound. Unable to perform well before the king, Khan asked for a few months to return and perform again in his presence. Khan got in touch with an instrument maker in Calcutta (now Kolkata) and developed a new instrument based on this Tanseni rabab. He added a metal plate to the surface, which became the fingerboard. He introduced metal strings in place of gut strings, replaced the small wooden resonator with a large gourd resonator similar to the one in the veena, and replaced the goat skin with wood. The replacements gave the sound a sharp clarity, which made it possible to execute long glissandos. This instrument came to be known as the sursingar in the Royal Court of Benaras.

Filling the gap

The sursingar has seen many modifications since Jaffar Khan’s time, and over the centuries.

My experiments involved modifications to the size and shape of the instruments. I tweaked the materials too. There was limited access to certain materials back in the 18th century when the instrument was first

made. Now there is an abundance of options, and I need to select them carefully for the ‘best’ sound.

The reason I attempted to revive the

sursingar was because I felt the sarod has some limitations; for example, it does not sustain notes for more than two or three seconds. As a musician regularly performing, I wanted to find a way to address this limitation. I looked at the instruments of my own gharana. The guitar and sitar are constantly renovated and updated. I thought why not try this with other Indian instruments.

I am a first generation professional musician. Formal education came first: I completed my engineering and MBA and emerged one of the toppers. I had a corporate job as a marketing consultant for about 11 years. I used to head a team and was required to delegate work to my teammates. While waiting for them to finish their tasks, I did my music practice. This I did by keeping a spare sarod in the security guards’ room at my office. Whenever I had a few minutes to spare, I would pick it up and practise. This was how I managed to hold down a full-time job and still focus on my music.

It took me about seven years to create the modern version of the sursingar. During the time, I also revived the Mohan veena created by my guru’s guru during 1943-48. This Mohan veena is a bridge between the sursingar and the sarod. It has the longer sustenance and resonance of the sursingar, the high speed playing capability of the sarod, and the tonal quality of the veena. It looks like a sarod as its fingerboard is a steel plate but the sound box resembles the minimised version of a sursingar. Thakur Jaidev Singh, the then chief producer of Akashvani, named this instrument Mohan veena in honour of Pandit Radhika Mohan Maitreya. This instrument was praised by several stalwarts, including Bharat Ratna Pandit Ravi Shankar, who wrote about it in his autobiography. I played this revived Mohan veena along with the sursingar at the G20 summit in New Delhi last year in the presence of ministers and world leaders.

One of the challenges of designing the sursingar was ensuring that its sound should match up to the surbahar and sitar and even the Rudra veena. The sitar produces a sweet sound, the surbahar is known for its deep tone, and the sound of the new version of the sursingar had to be on par. I came up with three to four iterations before settling on the best.

I followed the same procedure while reviving the sur-rabab and the Tanseni rabab. First, I had to understand the physical structure of these instruments and the sound they produced. My previous experiences gave me some insight. There are pictures of Tanseni rabab in old books. I also visited some museums to get a closer look. Then, I sketched possible new designs.

My engineering degree came in handy. I looked at what wood, strings and materials to use. I had to compare them with what was used earlier, and find replacements for materials now banned or hard to find. I have a collection of eight sarods and each is made from different wood. I carefully analysed what kind of sound each wood produces. I settled on 100-year-old mahogany wood for the rababs. Older wood produces a sweeter sound, and the wood I chose was well seasoned and lightweight. This is also the reason older musical instruments are highly valued.

Instrument maker

Finally I sat with the craftsman, Shambhu, and prepared a blueprint. I met him sometime around 2014. I was desperately looking for an instrument maker and had checked out the work of craftsmen from across the country. None of them had seemed to fit the bill. One day, Shambhu showed up at my house. He said he had heard I was working on reviving rare instruments and he wanted to work with me. He lives in a remote village of West Bengal. He was originally a sitar and tanpura maker. I then visited his house and saw his work. He is a master craftsman. However, he needed my help with the final touches.

After the designs were given to Shambhu, some months were spent on testing. The cutting and shaping had to be perfected, and we tested sample sounds with dummy instruments. I sought archival recordings of these instruments from the Sangeet Natak Akademi and Prasar Bharati.

I kept certain things in mind. First, we are living in the 21st century, in the age of AI, electronic gadgets, superfine instruments and cutting edge sound equipment. It was important that the instrument was modern. I kept in mind what present-day audiences like. While conceptualising the modifications, I tried to understand why people would listen to Tanseni rabab, the sur rabab or the sursingar alongside the sarod.

It was important not to deviate from tradition — I had to modernise the instruments while keeping tradition alive.

Today, Shambhu makes 18 types of string instruments. He even exports sursingars to France and the US under my supervision. I don’t regret quitting my high-paying job and venturing full time into music and the

preservation of our cultural heritage.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi appreciated my work on ‘Mann Ki Baat’ in February, 2023. My work also got recognition from Padma Bhushan Pandit Arvind Parikh, the senior most classical musician of our country, who invited me to play at his south Mumbai residence. He is known to only invite senior renowned artistes to his baithaks. The Ustad Bismillah Khan Yuva award from Sangeet Natak Akademi in Instrumental Music was also a big accolade in my life.

Viewers and subscribers on my YouTube channel have grown in a big way in the last three years. I am getting invited to play on various stages across the country.

I have no patents over the designs of the revived instruments, and I don’t plan to apply for any. Music should not be kept confined for personal profit. I am not the original inventor — I believe more people should start playing it. Only then I will feel that my work is a success. I have heard that some artistes are also getting sursingars crafted in Gujarat, Miraj and even Bengal, and practising the instrument indoors and on local stages. This resurgence was necessary. I wish them all the best. ‘Talim’ is important. One day I got a call from a foreigner. He had bought a sursingar similar to mine, but had no idea how to tune it, and needed my help. I told him he should have called me before ordering it. Fretless string instruments, like the sursingar and rabab, are not easy to play. Sursingar is especially not an instrument for a beginner. It is advisable to begin with the rabab or sarod and then move on to the sursingar.

Other revivals

I am not alone in making these contributions to ancient Indian instruments. My own gharana’s Somjit Dasgupta has been preserving 52 traditional instruments of Pandit Radhika Mohan Maitreya for the last 44 years. I got a chance to look at a 1911 sur-rabab from his collection. He is compiling all records, documents, letters and videos of the masters of our gharana.

Subhasis Sabyasachi, a percussionist in Delhi, is working on the revival of age-old traditional percussion instruments like the shruti, awaz, and dunduvi, as also the 500-year-old mridang and brojatarang. Jyoti Chowdhuri of Maihar, Madhya Pradesh, is playing the nal-tarang of Baba Allauddin Khan. He had developed it from the barrel of the rejected guns of the Maharaja of Maihar during the late 19th century.

A few years ago, Tharun Sekar revived the yazh — an ancient Tamil instrument. Though I personally haven’t met Sekar, I hope to meet him some day and do some work together.