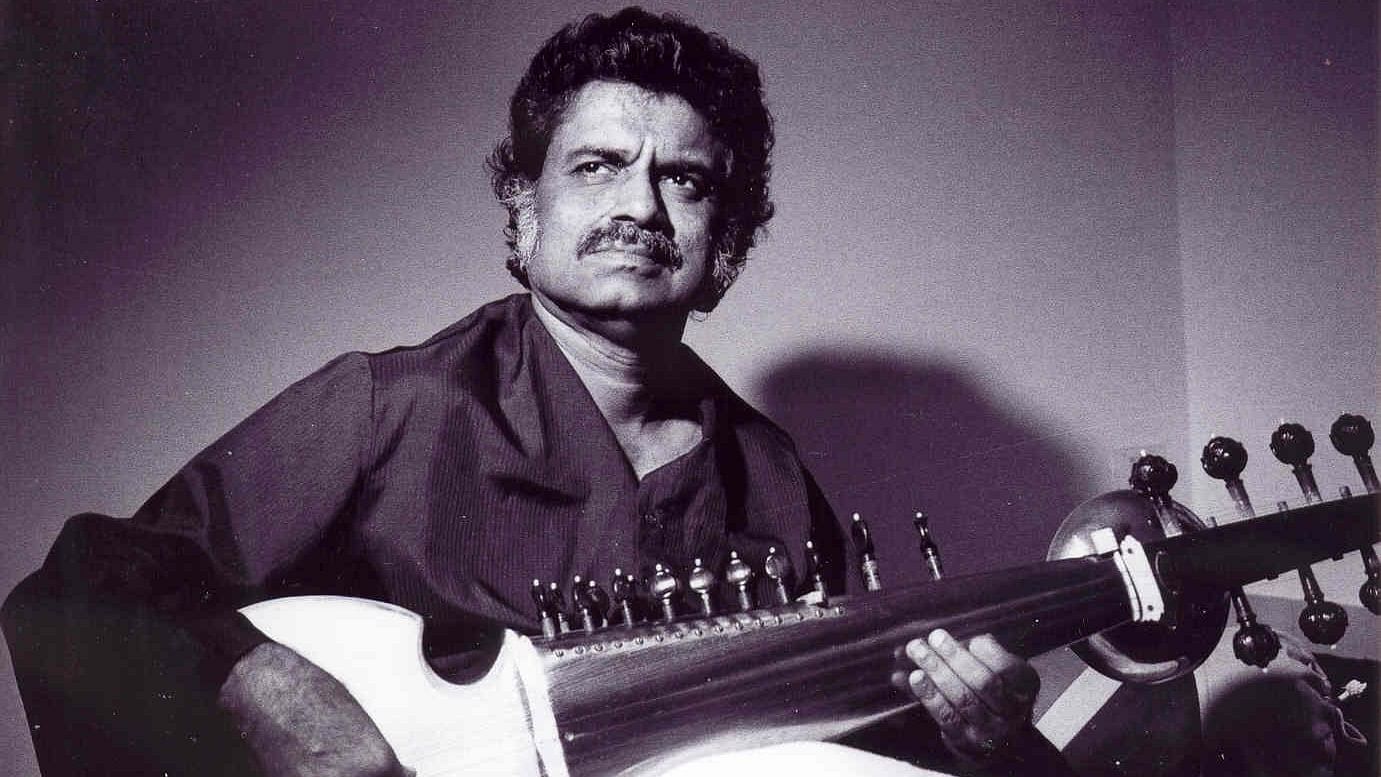

Rajeev Taranath

Six months ago, I got a call and a deep voice said, “Am I speaking to Rumi Harish?” I knew who it was. I dropped the phone in excitement, and then quickly picked it up. The voice said, “I am Rajeev Taranath”. I stammered, “Sir, sir, yes, I know.”

Years ago, he had asked me to perform for the Taranath Foundation. He had said I had his mother’s name Sumati, and he felt good to see me chatting and singing. But this time, he did not utter a word about my dead name, or his mother’s name. He was so sensitive about my transition.

As a student of Pandit Ramarao Naik, I had sung in his presence since my childhood days. He was a phenomenon, known for his intensity and deep knowledge of the ragas. This time, he started talking about how he was impressed with ‘Jaunpuri Khayaal’, a book written by Dadapeer Jyman about my life. He congratulated the two of us.I suspected he had not recognised who I was, and mentioned my dead name to tell him who I was. He paused, and said that he did not want to hurt my sentiments by talking about that name. It was like a moment where my taan (fast phrases) went off track and got reined back in. I couldn’t have asked for a better acceptance; many of my own people have not acknowledged my changed being. Not once did he bulldoze me with platitudes, as the elderly often do. He chatted happily about Mysuru, where he lived, music, and a bunch of other things.

One day, he called and said, “Hello Rumi, I want to ask you something, but I don’t want you to misunderstand me.” Immediately, I thought I knew where it was going and cursed all cis men for their curiosity about the anatomy of my manhood. I steeled myself to talk about my gender surgery. What came from him was totally unexpected. He said, “So, you have done gender transition, but have you done voice transition?”

I blabbered an incoherent answer. “Wait, are you on testosterone? Has your singing voice broken?” His questions soothed me. This act of compassion is extremely rare. In his teen years, his voice had broken and he had not been able to sing. He asked me what I was doing. I began explaining everything that I had gone through to sing after my transition. He said, “Listen, come to me, I will help you out. Don’t keep waiting for your voice to get better… If I could start learning the sarod at 51, you can now sing with the voice you have.”

I had approached many musicians seeking help to sing through this transition. They had avoided me because of my identity or were clueless about how to train me in this phase. This had pushed me into despair. But that call brought back my guru Ramarao to me.

Disillusioned by classical music circles and the people in it (with a few exceptions) I had stopped attending concerts; I had even stopped listening to music. I felt guilty--I had followed my heart to be what I was today, but had not asked my voice what it wanted. I could not sing for a year and a half. My voice was broken and sounded like a bark. I was not sure whether I wanted my singing flexibility back or the voice of my previous gender. While I continued to live with a shaky voice, I did everything possible to bring back my singing. I succeeded to an extent and was able to get some stability in my voice.

From February this year till June 11, when Taranath died, I was transported to a different world altogether. When I went to see him in Mysuru, he said, “You have not lost your singing. Why worry, just sing. Everything will fall into its place. Mind you, I will be a tough teacher.” He laughed like a baby, and his eyes said a lot more. He kept singing all the time I was there. He just wouldn’t stop, from raga to raga, thumri to dadra, he sang and made me sing too. That’s when I realised that riyaz (music practice) is not something we do for a few hours. It is a way of life — you are immersed in thoughts of music, and you take off on the wings of your thoughts.

Lalit is a raga with a complicated scale. My first class began with him singing Lalit. I was repeating what he sang, and he stopped me. He said, “Don’t parrot me. That is to learn the notes, and you have already done that. Follow my thoughts, see the journey of my thoughts, allow me to see your thoughts and challenge me. The most beautiful part of music is the movement you create and the density of the notes you construct in the abstract. Yet, you have to see it, see the line of movement, see how you construct a thought.” I sighed, trying to grasp the thought, and he sang more complex ragas related to Lalit. I was trailing. This experience reminded me of Aditi Upadhya (one of my teachers and daughter of the illustrious singer and composer Pandit Dinkar Kaikini). She leads, and helps students construct thoughts in music to make it into a poem or verse.

Finding the keynote

Given my situation in life, I could not go to Mysore as frequently as I wished. I requested him to reduce the frequency of my classes. That did not go down well with him. But within two days, he called me back and insisted that I take more frequent, online classes. He was undeterred and had taken up the challenge of training me. “Keep seeking your sa (the first note). Seek till you are a beggar before the note, till you breathe your last,” was his advice.

When I went to see him, a day before he breathed his last, I stood looking at him in the ICU, knowing that all of us students would soon face a void.

I came out numb. One of his friends, in the waiting room, said: “Rajeev gave me your book and shared the story of how you tried to learn from musicians who turned you down. He said it is a mistake if we don’t teach people from diverse identities. Who are we to stop the river of music? He said if he didn’t teach Rumi, he would be betraying our history of music”. I was overwhelmed.

Taranath is a phenomenon that touched many lives, but for him to take me into his fold, breaking all conservative dogmas, is to practise the politics of love. It does not discriminate, and it gives us the dignity and confidence to live. I won’t say thank you Rajeev. I now have a mission in my life — seeking my sa — and that is a tribute that I will pay for a lifetime.