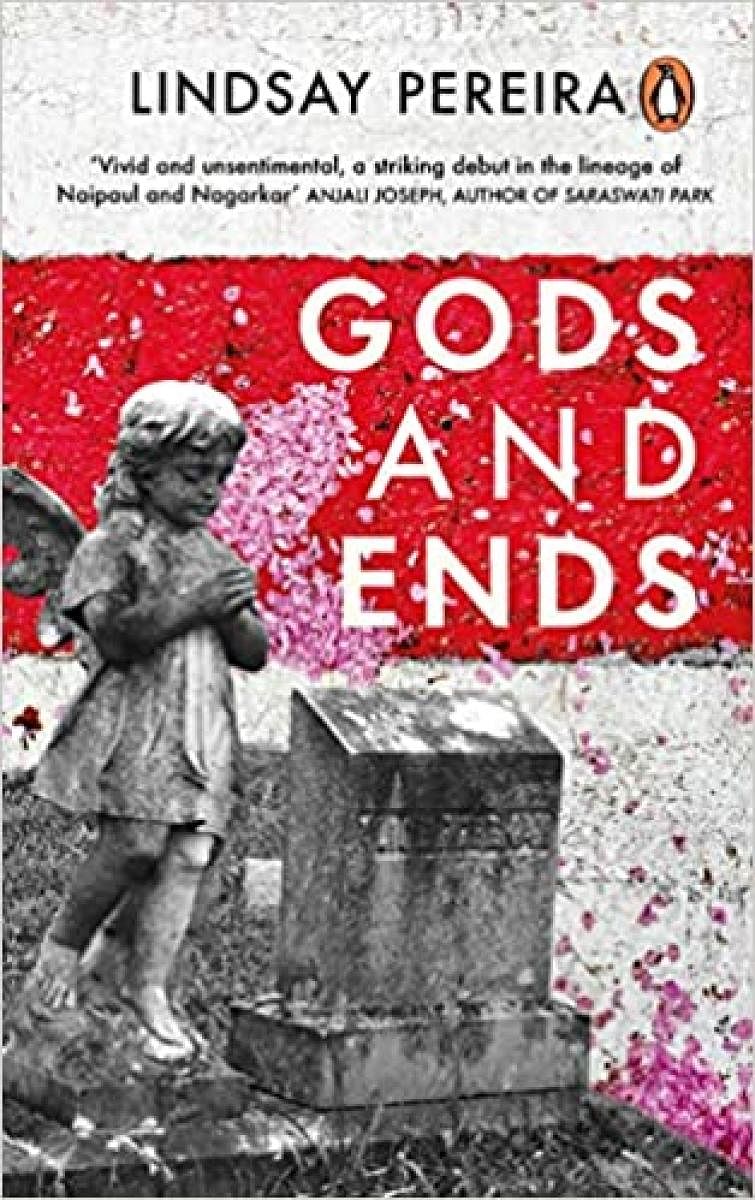

Fiction is sacred: a fact too many book lovers ignore. Especially fiction that is not preachy, partisan or journalistic; does not set out to achieve anything except tell a pristine story burning within its teller. Ergo, each new voice in fiction is to be welcomed. And by glowing in parts, Lindsay Pereira demonstrates he can write with both skill and finesse.

Writing about a building and its inhabitants is not entirely new a ploy. It is clever though, binding a motley crew together by poverty, religious identity and low rent. Obrigado Mansion watches its neighbours go to seed and get sold to builders while itself dwarfed by tall replacement apartments all around, holding out as a minuscule moment of defiance against the tides of time.

Its inhabitants are flotsam tossed into the backwaters by diminishing fates, washing up at Obrigado’s paper-thin walls, filth and overflowing common toilets. And existence here is so vile it is almost cursed. The life stories unfolding here are unremarkable to the point of being wholly uninteresting. The women are washed out. The men resigned. Their children only dream of escape. For most of the inhabitants of Obrigado Mansions, this is a dead end relieved by dreams of elsewhere though they know already, quite like their landlord Francisco Fernandez and the old widow Bella Quadros, they will leave only in a casket. As distractions, booze and violence serve to only distil their sense of despair.

Aching hearts

Each chapter in the book belongs to a character. Their stories crisscross as they weave the rough hessian of the book’s underside. Most often, it is the invisible narrator capturing in broad strokes the few defining features of a longish dreary life. Some characters speak of others more than they speak of themselves. Others still spill all they hold in their aching hearts almost treating the pages as a confessional. It mirrors the confessional Father Lawrence Gonsalves presides over, prescribing Hail Mary and Our Father in Heaven prayers to sundry sinners while unable to counter the sins that rage within him.

In its essence, this book is about neither gods nor ends, but about lusts and human frailty. The women are all deluded to a point. The widow sinks into a thankless existence, but believes in a blessed afterlife as reward for her dutiful pious ways. The widowed daughter-in-law is left alone and ignored. The wife, who is being cheated on, turns her bitterness inward; for, you see, a farcical happy marriage is the better alternative. One of the wives being battered is filled with rage, but not towards her aggressor, preferring instead to rain abuses on her neighbours, while the other finds her way out never to return. Women gossip. They size each other by the cost of the fish they buy. They fade away and rot in terribly lonely thankless lives. Or they turn, in sinister ways.

Unmade promises

The men are mere caricatures of what men must be. Some fade in anger and silence. Some find mistresses while preaching the holy word. Some drink into oblivion. Most turn to some form of violence on the women in their lives. All of them believe in unmade promises and fuel themselves on lust. And they cannot love.

There are moments of celebration: weddings, Christmas, funerals and a party on their terrace once they’d contributed money and food trays for. Heck, even Jude Sequeira being shoved into the well he is drunk-pissing into, could be a celebration for some.

Orlem in Malad, north Mumbai, is defined by Our Lady of Lourdes or simply Orlem Church (1916) and in 2004, was declared the largest parish in the archdiocese of Mumbai.

This story, set on a lane hard by the church, bypasses entirely the sizeable local East Indian community here to focus on Goans with a stray mention of a “mangy” from Mangaluru somewhere. The Christian community is India is layered, colourful and rich in their stories. This could have been an insider’s nuanced bioscope, affording readers a privileged peep into a fascinating world so near and yet so unexplored.

Surprisingly, every dirty filmy stereotype about the Goan Christian community is at play within these pages: short skirts, alcoholism, violence, illiteracy, sexual promiscuity and filth. The choice of using the tired ‘dat bugger’s mad or wot’, kind of pidgin dialect in large passages is not the smartest. But what really curls the toes is the relentless fat-shaming of 12-year-old Philomena. There are graphic descriptions of how her ass looks in a shiny skirt walking up for holy communion at Easter mass. Not once does she appear without someone commenting on how much she eats.

There are places we walk past but never visit like the country liquor bar, Eddie’s. There are people we see but don’t know. This book perhaps, is a first step in learning to focus our gaze.