The cast of characters are familiar, the events — much of it at least — are all too well-known to anyone who regularly flips through newspapers or popular magazines. Yet, questions remain: Has the modern (book-reading) literate audience actually understood the two most important architects of Hindutva in their many contexts?

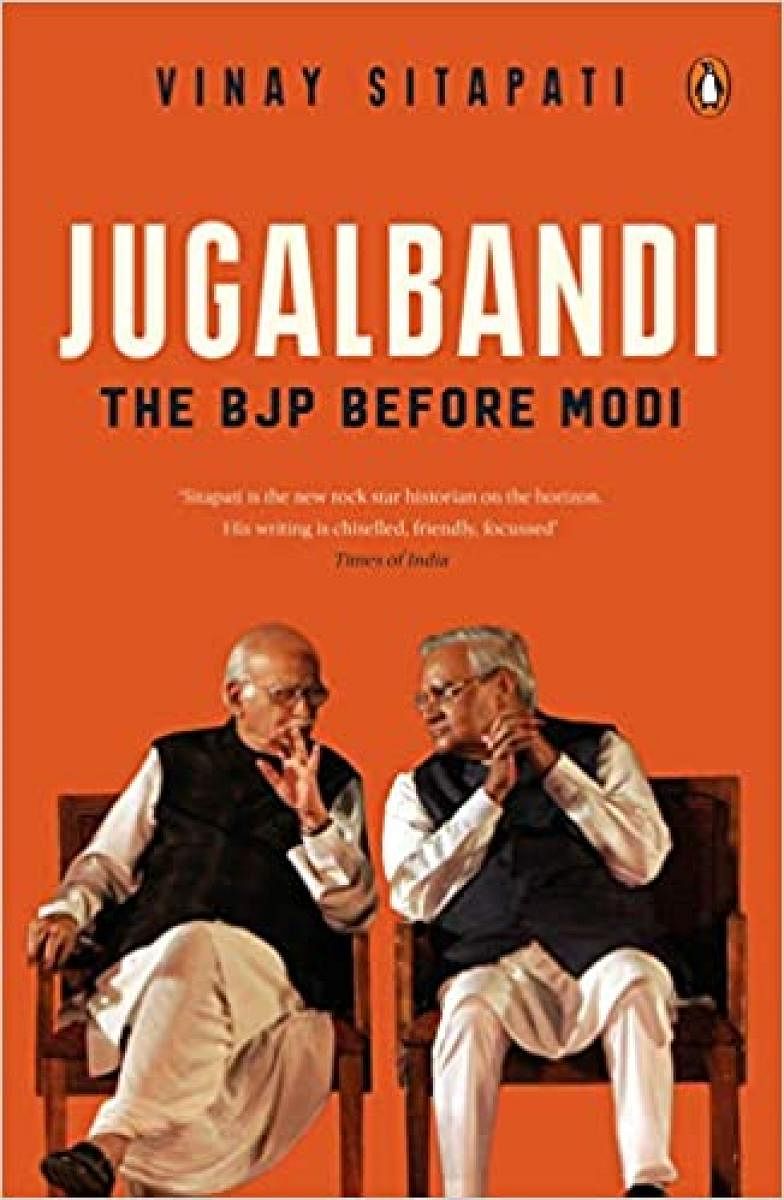

If the millennials have heard about Atal Bihari Vajpayee and Lal Krishna Advani, two endearing figures with roots in a divisive ideology and struggled to reconcile the apparent contradiction of their softer nature with their hardline politics, Vinay Sitapati’s latest book, Jugalbandi: The BJP before Modi, will offer them the elements connecting their personalities with the period their careers flourished.

Sitapati traces the success of the present-day BJP to the blueprint created in the 1920s by men who saw Hindu majority as an ideal (and durable) vote bank that could be pitted against the minorities; the ideology that gave birth to the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). Only, the organisation had to first survive banishment after it was accused of playing a role in Mahatma Gandhi’s assassination in 1948.

While Shyama Prasad Mukherjee and Deendayal Upadhyaya gradually brought the ideology, (in the form of Bharatiya Jana Sangh), back into the mainstream dominated by Nehruvian ideas, it needed Vajpayee and Advani to help it find a niche in the post-Nehruvian political scene. The duo stood up to the task by forging a partnership that lasted for more than half a century.

At its core, Jugalbandi is a Kane and Abel story depicted on a political canvas. Unlike the Jeffrey Archer tale, Vajpayee, son of a poor Brahmin teacher and Advani, a refugee to India from the communally diverse Karachi, were welded together in the Hindutva cauldron.

Their relationship, at the outset, is one of mutual admiration and certain shared hobbies like movie watching.

If Advani was bewitched by Vajpayee’s lyrical Hindi rhetoric, the older man was impressed with the way the English-educated pracharak managed organisational issues. It largely stayed that way, Vajpayee leading the party in Parliament and Advani outside of it.

Ideological moorings

The duo played a delicate political duet; doubling up their strengths and letting the other step in when weakness or inadequacy could ruin the progress of the larger cause. Sitapati finds elements in their ideological moorings to explain their loyalty to each other and how, magically, they managed to avoid an ugly fallout, despite coming close to it on a few occasions.

That’s how Vajpayee took his political marginalisation in silence (his comment that corrections happen in the margins being so telling) even as Advani was busy charming his devotee-voters greeting his modern Rath with flowers and aartis.

And a realistic Advani declaring his older companion prime ministerial candidate when his party expected him to assume leadership, knowing that Vajpayee’s softer image was an asset in coalition building.

Political books stand out as exceptional works when they manage to go beyond the facts and shine a light on the human side. Jugalbandi achieves that specifically in two places; capturing Advani’s pain as he watched the domes of the Babri Masjid collapse and Vajpayee’s frustrations as he draws his pen to sign his resignation letter in the aftermath of the Gujarat riots.

While it may be true that both had pushed the limits when it came to Hindutva, they never would’ve liked to cross the line, especially when they wanted to balance galvanizing their political base with coalition building.

Ironical moments

These are also two ironical moments in the sense that when Hindutva seemed to be succeeding, the two architects were not finding it enjoyable.

It’s also ironical that their political project found its most effective (and successful) laboratory in Gujarat, when the same had marked the lowest point of their time in power.

As in his previous book on P V Narasimha Rao (Half-Lion), Sitapati has this canny skill of blending storytelling with scholarly discipline. Without this rigour, the book would’ve ended up becoming a cheerleader’s tribute or, worse, one that played to the gallery.

But, on the contrary, it offers the right perspective on the life and times of two important leaders and traces the evolution of an ideology that came out of banishment to acceptability and eventual domination in a polarised nation.