If money is the measure of wealth, currency is the measure of money. A rupee is a piece of metal in the pocket or ledger data in the bank. But when it moves from one person to another, it becomes valuable. Money must flow. Money is the currency itself. The coin rocks only when it rolls.

Software and data are no different from money. Information has value only when it moves, only when it is communicated. Indeed, Claude Shannon, the father of information theory, titled his historic paper ‘A Mathematical Theory of Communication’. It was this theory of ‘communication’ that flagged off the Information Technology revolution.

Look around you: your phone, your computer, the wireless protocols, the radio signals, the optical fibre, the Internet; they all ceaselessly move bits of information around. As though the spinning of the Earth depended on the shunting around of a gazillion bits in the span of every tick of the clock. Bandwidth does make the world go round.

This is the story of how bandwidth changed the destiny of India, first, through the software industry and then through its offspring, the BPO industry. Modern Indian culture and attitudes towards work and play are a product of how bandwidth evolved in the country and the role NASSCOM played in it.

The modem generation

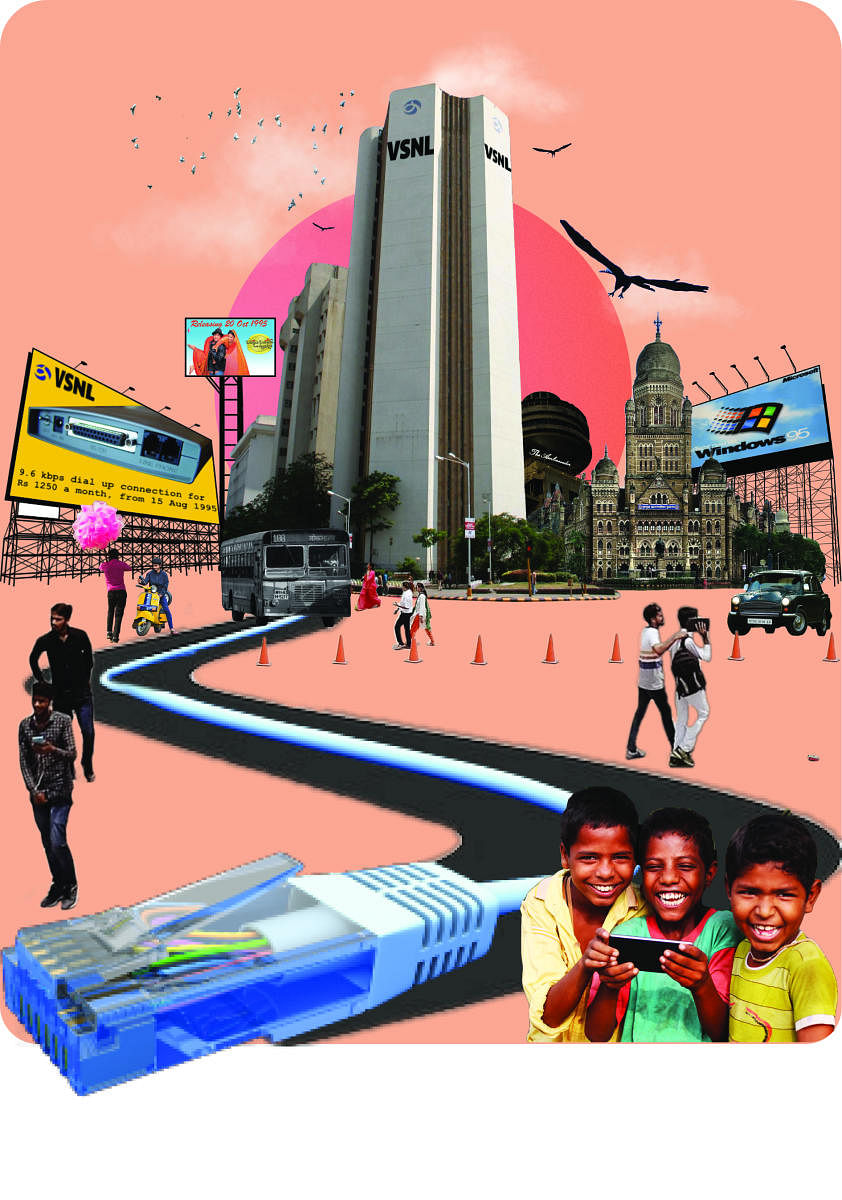

At the time of writing this, India already has over half a billion people plugged into the Internet. Even a minimum wage earner has a smartphone in their pocket. A news report pointed out that data in India is the cheapest. The average cost is $0.20 per GB. That’s over four times cheaper than nearest contender Russia’s $0.90. Malaysia is at $1.1, Pakistan at $1.8, Nigeria at $2.2, Brazil at $3.5, Spain at $3.7, the UK at $6.6, Germany at $6.9, China at $9.8, Canada at $12, the US at $12.3, South Korea at $15, and Switzerland at $20.2. Consequently, sites like YouTube, Facebook and Instagram see significant traffic from India.

Indians today consume data like they breathe in air. But this was not always the case. In the 1980s and 1990s, the IT industry’s annual bandwidth diet must be what a teenager today burns through in a weekend. It will be amusing to explain to this teenager what a 9.8 kbps (kilobytes per second) connection feels like. How it was normal to wait several minutes for a few KBs (kilobytes) of GIF (graphics interchange format) to show up.

The larger experience went beyond sluggish. It was outright clunky. Getting online was a ritual. You hooked a computer to a modem that would, in turn, be hooked to a phone line. The modem would screech and squawk until you got connected, sometimes after fifteen minutes, often an hour. If you got online, you could only hope nobody called your phone because that would lead to disconnection, forcing you to repeat the mind-numbing ritual. Yet, such was the romance, the modem’s torturous sound is today sweet nostalgia to all those who once endured it.

Insurmountable challenges

In the 1980s, as a partner at Hinditron, I witnessed genuinely insurmountable challenges in data transfer. Yet, the technology promised to ring in the future. In 1982, for a Computer Society of India (CSI) annual event, we worked with the Department of Telecommunications (DoT) to set up a data link between Mumbai and Pune. The experimental link was used for showcasing remote computing. I wrote the application that would use CSI’s dedicated data link to connect a desktop computer at Pune to a database of CSI members running on a DEC computer stationed 160 kilometres away at the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR) in Bombay. Dr Sadanandan of TIFR was my partner on the project and Dr Narsimhan, a director at TIFR, was my mentor.

On the day of the demonstration, everybody was amazed. It felt like magic, and people were fired up by its potential. If this could be scaled, one could service any client sitting anywhere in the world. But our hopes were deflated when we asked DoT to actually scale it. They had no answer.

We already had international clients. But our engineers could not serve them out of India because the cost of transferring data would destroy our financial model. The other route was to mail them floppies and tapes. That was cumbersome, unreliable and uneconomical. So, we continued to deploy our engineers at client locations across the world. Setting up a nearshore centre, closer to the customer, was only a dream. There were umpteen regulations preventing that.

Needed: A fast data link

Government policies had us dealing with typical third-world problems, fighting fires all the time. The IT industry was not yet Delhi’s favourite, and we were still to be seen as creators of livelihoods and earners of foreign exchange. Nonetheless, we knew all along, that the offshoring industry was not going anywhere without connectivity.

In the late 1980s, we approached Sam Pitroda, the then advisor to Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi. We told him that we needed a fast data link between India and the US. He told us the government couldn’t afford leasing one because the balance of payments crisis had left it with little foreign exchange. We persisted. We asked him if he believed the IT industry’s exports could grow. He said he did. Then we asked him if he preferred body shopping of Indian engineers or their offshore work. He preferred their offshore work. Once again, we turned it around and asked him how we could do any offshore work without the data link. But Sam Pitroda apologised and reiterated that he did not have the money for it. We had failed to convey the confidence we had in our vision.

1995: The year of the internet

A little earlier, in 1986, the public sector enterprise Videsh Sanchar Nigam Limited (VSNL) was set up to improve international communications. It commissioned the first analog link connecting India to the US. This must not be confused with the Internet, which came a decade later. This link could also send data between a location in India and another in the US. Before this, data in India was very much a physical object that travelled as floppies and hard disks.

The pioneering 9.8 kbps line was not the revolution you may have imagined. In fact, it was useless. The speed on this analog link was impractically slow, even for those days. Besides, the line was faulty and kept disconnecting every few minutes. Each time we lost connection, we had to restart the transfer from scratch. Transferring even a few MBs (megabytes) would require several attempts, leaving us exasperated. To keep our sanity, we innovated. If we had to send a 10 MB file, we broke it into three smaller files. Now, if the transfer failed, we didn’t have to resend the entire 10 MB.

The Internet has existed in India since 1987 in the shape of ERNET. ERNET was initiated in 1986 by the Department of Electronics (DoE), with funding support from the Government of India and the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), involving eight premier institutions as participating agencies — NCST (National Centre for Software Technology) Bombay, IISc (Indian Institute of Science) Bangalore, five IITs (Indian Institutes of Technology) at Delhi, Bombay, Kanpur, Kharagpur and Madras, and the DoE, New Delhi.

Internet, as we know it, was launched by VSNL in India in 1995. Further, the ISP policy came into effect in 1998 and it allowed private players to offer Internet services in India.

Hope floats

Nevertheless, the data link inspired hope, and in the early 1980s, we at Hinditron pitched for an offshoring project to a new client in the US — Amcor. The only Indian Amcor’s CEO knew was his doctor, and he thus regarded Indians highly. But we soon lost the contract as poor connectivity bedevilled us. Amcor was not an isolated case. Our conversion rate for offshoring projects was incredibly low. And the ones we converted, we struggled to retain. Data links were not just bad; they were expensive. Today, project managers do not think about data transfer costs, but in those days, we would keep aside 7–10 per cent of our revenues for it. A 64 kbps link used to cost ₹20,00,000 per year in the 1990s. With such a high upfront cost, many were deterred from starting a software services business.

If there was ever a need for an industry association, this was the time. The signals couldn’t have been stronger or clearer.

In 1991, VSNL got a new chairperson, B K Syngal. We met Syngal at his Fort office in Mumbai. Right away, we asked him for 64 kbps lines. We were asked why we needed those higher speeds when we were not using the 9.8 kbps lines for 90 per cent of the time. The irony was that we couldn’t. It just did not meet our requirements. We tried explaining that if a customer needed something important, the data had to be at his desk in an hour. If it took fifteen tries and seven hours to do that, it wouldn’t work for us. It was ridiculous to engage our top engineers, who would then simply wait for data transfers.

Syngal challenged us to lease fifteen 64 kbps links. He was afraid our industry couldn’t absorb those. His concern couldn’t have been more misplaced, as industry leader TCS coolly said it would take all fifteen links. Syngal was astonished. He enthusiastically assured us that VSNL would work with global telecom providers and start giving us links in six months. He warned they would be expensive, and he would try to provide them to us at a slightly lower rate than the prevailing global prices.

We were elated. The data transfer that took days could now be done in hours. At the time, the speed was state of the art. It felt like the future had suddenly arrived. The amount of work we could service with this speed was massive. We could now pitch to Fortune 500 companies and expand our market tenfold overnight.

On the edge

Before 1991, connectivity was limited to two small analog cables with limited capacity. Satellite links through the new earth stations too were not what we ordered: a single-hop transmission, where the signal is bounced off a satellite only once, was required. But the ones we got used multiple hops, and that dropped data and caused latency, especially at higher volumes and speeds.

Would India’s potential as an offshoring destination collapse just because of poor infrastructure? After Sam Pitroda, Syngal struggled to respond, too. Despair set in as contracts were lost due to a lack of basic delivery systems. The IT industry was at the edge of a precipice. We needed a physical route to the West. There was one, an undersea cable laid by a consortium of countries. It was called the SEA-ME-WE (SE Asia, Middle East, Western Europe cable). India was not even thinking about data when it was commissioned in 1985. The opportunity had been missed. But fortune knocked a second time.

Another undersea cable was being sunk to the ocean floor.

Excerpted with permission from ‘The Maverick Effect’ by Harish Mehta, published by HarperBusiness

The author is the founding member and the first elected chairman of NASSCOM, a not-for-profit organisation representing India’s IT industry and considered among the world’s most exemplary associations. As a prominent angel investor, he also spends time mentoring young entrepreneurs.