In her dream, Karuppayee was a young girl once again, rummaging through her old trunk for something, though she didn’t know for what. All of a sudden, she found herself standing in the middle of the groundnut field. It was a moonlit night and there was a figure in white standing in front of her. When she saw its face, she opened her mouth to scream, but no sound came out. She woke up with a start.

It was the crack of dawn and the rooster had started crowing. Though Karuppayee no longer carried out the household chores, the decades-old habit of rising early was tough to break out of. Her daughter-in-law Lakshmi was putting out feed for the cows, while her son Thangavelu was rinsing out the pails he would use for milking. He would soon cycle to the town to deliver the milk and spend the rest of the day working in the field. Her granddaughter would join the morning hustle and bustle by drawing water from the well and helping her mother light the wood fire in the kitchen, before leaving for school.

When Karuppayee saw her granddaughter loitering aimlessly outside the house, she called out to her. “Thilaga, come here. Don’t you have to go to school today?”

“Aiyyo, paati! You are so dumb. Today is Sunday!” she replied.

Karuppayee nodded sagely, “That’s true, paati doesn’t know anything. After all, I didn’t go to school and learn anything, did I?”

Thilaga giggled and skipped away to play hopscotch by herself.

When Karuppayee had been a child of six, she had asked her mother, “Amma, why did you give me such a silly name?”

Her mother, who had been grinding idli batter on the stone mortar, had said that when she was born, her skin had been dark as the night and the white of her eyes had stood out in stark contrast, along with the pinkness of her tongue when she opened her mouth to cry in the wretched way that only newborns do. She had been named ‘Karuppayee’, ‘the black one’.

Her mother continued, “It was only after slathering you in turmeric and gram-flour paste for years that your complexion lightened to an extent.” That it was not light enough was left unsaid.

Breakfast was the previous day’s rice and rasam. Thilaga was perched near her, eating her share of the food. Karuppayee said, “Have I told you about the meen kozhambu my mother used to make? She would make it in a rich curry of tamarind and chilli powder. It was so fragrant you could smell it all the way from the field, and so tasty you would keep licking your fingers till the last drop was gone.”

Thilaga responded with a sly smile, “Paati, you are trying to say my amma has not been making meen kozhambu and giving you, aren’t you?”

“No, no, I didn’t mean that,” Karuppayee said hastily, turning around to check if Lakshmi was listening to the conversation.

Thilaga said, “Don’t worry, paati, when anna comes from Madras on leave, amma will make lip-smacking meen kozhambu and chicken curry.”

That set Karuppayee off on one of her pet peeves. “Why did Kannan have to go to Madras? He could have helped his father by working in the fields here, or if that was not good enough for him, we have such a big town nearby. He could have found a job there.”

Thilaga could not stop giggling. She said, “Aiyyo paati… Madras is 10 times the size of Mettur. Do you know the shop he works in has thousands of sarees in the colours of the rainbow, spread across many floors? Have you ever seen such a shop?”

“How will I, child? I have lived in Poraiyur all my life. I have gone to the town two or three times in all these years. The cars and buses, the noise and the crowds! Appappa! So scary!”

Thilaga tapped her lightly on the head like she was a small child and said, “You are such a fool, paati.”

Karuppayee had been 10 when she went with her mother and aunt to see the Murugan kovil thiruvizha during Thaipusam. The pookavadi, huge pots decorated with flowers, balanced on the heads of the devotees, and the thol kavadi, adorned with peacock feathers, had her watching them wide-eyed and slack-jawed. Her favourite was the street-theatre troupe that would put up plays based on stories from mythologies in colloquial Tamil, combining drama and comedy.

That night, the play was the story of demon brothers Vatapi and Ilvala. Vatapi had been granted the boon of transformation, while Ilvala knew the mritasanjivani mantra that could bring the dead back to life. The demons used these powers to loot and kill Brahmins. Once, they invited sage Agastya for a feast. Vatapi turned himself into a goat and was killed and cooked by Ilvala, and served to Agastya. After the sage partook the meal, Ilvala chanted the mantra and shouted out to his brother, asking him to tear Agastya’s belly and come out. But the sage, who knew what the brothers were up to, used his divine powers to digest the demon in his stomach. The scared Ilvala shouting, “Vatapi, vellille vaada,” had the entire audience in splits.

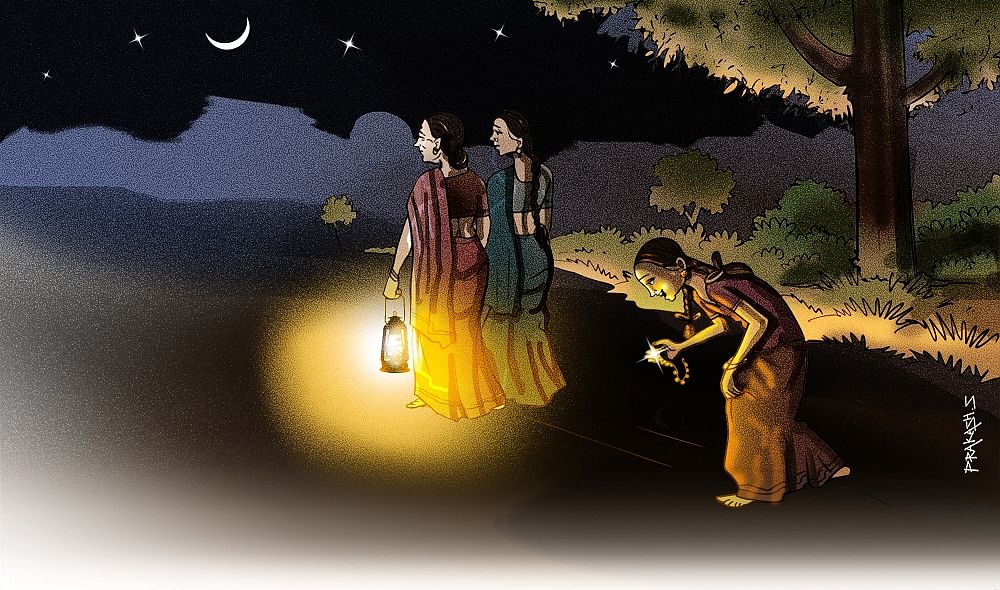

On the way back, Karuppayee closely followed her mother and aunt, keeping close to the light of the lanterns that swung in their hands, illuminating the path in golden pockets. They were nearing the tamarind tree and Karuppayee knew all about the resident ghost who kept a watch for lonely travellers from its leafy branches. Her eyes caught a metallic gleam on one side of the path, and she stooped to pick up a beautiful silver anklet.

In the days that followed, Karuppayee would finish her chores in a hurry so she could examine the anklet once again. She had her own anklets, thin strings of beaten silver, like most girls in the village. The anklet she found, studded as it was with red and green sparkling stones, was nothing like the anklets she had ever seen.

Every time she walked along the path to the temple in the months after, she would look out for its twin. It never struck her that the anklet must have fallen off a child’s foot, and it was highly unlikely that the other anklet had fallen off as well. To her, it was half a treasure found, with the other half waiting just for her. Every night, she would take the anklet out from its hideout in the bottom of the trunk and watch it sparkle in the moonlight. When she tied it around her ankle or dangled it on a wrist, she would be transformed into a princess, with a palace and with people ‘oohing’ and ‘aahing’ over how impressive she was. All she had to do now was somehow find the other anklet, and she could claim her destiny.

The next day, Thangavelu had to go to the wholesaler to sell the first crop of groundnuts. Lakshmi had cut her foot on a sharp stone near the well while washing the vessels at night. She had limped up to Karupayee and asked, “Amma, can you deliver the milk tomorrow morning?”

Karuppayee had said, “Of course, I can. I have done it for so many decades. Besides, I am not that old yet.”

As she trudged through the fields, she knew she would be exhausted by the end of the day, but she was looking forward to the change in her routine.

By the time she reached the engineer’s house, the sun was high in the sky. As the lady of the house took the milk from her, she said, “Wait for five minutes, there’s a phone call for you.”

Karuppayee had heard all about the telephone from Thilaga, but had never seen one before. At the shrill cry from the ominous-looking instrument, the lady picked up the receiver and handed it over to Karuppayee, showing her how to hold it.

She could hear her grandson’s voice from it, “Paati, why didn’t appa come to deliver the milk today? Can you hear me?” On hearing his voice, Karuppayee was flustered and spontaneously looked around to see if Kannan was standing nearby. All she could bring herself to say was his name, “Kanna, Kanna!” and her voice started quavering. Kannan was saying something about a parcel that would come in the post. After handing the phone back, she wiped her eyes with a corner of her saree. The children of the house were standing around and giggling at the silly old lady. The lady of the house said, “What is this paalkari amma? It is 1990 and you can’t even talk on a phone. Which century are you living in?”

When she got married to her cousin, to whom she had been betrothed since birth, her mother had wanted to sell the anklet and use the money for the wedding expenses. After all, what use was a single anklet? She had shed tears and refused to eat, and her mother had given in and left the anklet alone. Later, when she needed money for Thangavelu’s marriage, she had considered selling it along with her late husband’s watch. But she could not bring herself to do it and the watch was kept away safely for the yet-to-be-born grandson. The anklet went back into the trunk. Karuppayee had washed vessels in a few households for several months to raise money for the marriage.

Postman aiyya was sitting on the coir cot outside the house, sipping the buttermilk that Lakshmi had given him. He had come a long way to deliver the parcel to their house, riding his cycle for a few kilometres through the fields. So refreshments were expected.

The parcel had been opened by an enthusiastic Thilaga and now she was prancing about wearing the new earrings and glass bangles sent by her brother. Even Lakshmi’s tired face had broken into an uncharacteristic grin, as she admired her gift, a yellow saree with big red and orange flowers. Unlike the coarse cotton that the women were used to, the material was soft to the touch and shimmery in the sunlight as if it had a life of its own.

Though Karuppayee was taking in the scene around her, her attention kept reverting to the little box lying open in her hand. It held a single anklet with red and green stones, the exact duplicate of the one lying in her trunk. This one had the whiteness of new silver, unlike the old one that had oxidised into grey-black with age. Of course, that didn’t matter. Once the silversmith polished it, it would be shiny-new again. Karuppayee was in shock though. She knew she had told the story of the anklet to her grandchildren hundreds of times. It had been a favourite of Kannan’s. When he was five or six, he would lie down with her and pester her for the story of the anklet. As he became older, he preferred listening to ghost stories, and as the months and years went by, he had stopped asking for stories.

That evening, Karuppayee called out to her son and handed over the box with both anklets, old and new. “When you go to town next, get the old one polished so that Thilaga can start wearing them.” Thangavelu looked questioningly at her for a moment, and then silently took the box from her.

Karuppayee continued sitting on the coir cot, looking out at the fields. She did not need the anklets anymore. She had the story with her forever, to tell Thilaga, to tell anyone who would listen. But then, who was telling the story? And whose story was it anyway? The words fluttered and flew in the wind. The palm leaves were swaying in the gentle evening breeze. The air was rent with cries of birds returning to their nest. The sky was painted in pink and orange. The sun would set soon. It was time to sleep.

Also read:

Meeting Old Age (The First Prize-winning story by Smitha Murthy)

An Appetite For Drama (The Second Prize-winning story by Pritika Rao)