The pandemic has disrupted the celebrations to mark the birth centenary of Pandit Ravi Shankar (1920-2012), the legend who took Indian classical music to the West and was regarded by George Harrison, guitarist of The Beatles, as the ‘godfather of world music.’

This is perhaps a good time to reread Ravi Shankar’s autobiography, Raga Mala, to look back at the truly magnificent strides he took. The hardbound edition is beautifully produced; it is a book to treasure. Published in 1997, it has additional notes by Oliver Craske, a grateful foreword by Harrison, and beautiful pictures. A new book by Craske — Indian Sun, The Life and Music of Ravi Shankar — was launched earlier this year.

Raga Mala chronicles not just the life and times of “one of the greatest musicians that ever lived” (Anoushka’s words), but also the dramatic advent of Indian classical music in the UK and the USA.

Educating the ‘whites’

Before Ravi Shankar initiated foreign diplomats in Delhi to Hindustani music, they were unresponsive, some even comparing it to the meowing of a cat. It took someone with his charisma to draw them in, with lucid explanations in English. The tipping point came in 1966 when Harrison came down to Mumbai and started learning Indian music from him. By then, The Beatles were a worldwide phenomenon. Ravi Shankar became a cult figure, and was co-opted by the hippie movement and the Vietnam War protests. He was soon in huge demand for concerts across the world.

Thanks to his efforts, Harrison says, “The world is now permeated with the acceptance of Indian music.” A huge body of Ravi Shankar’s path-breaking work was recorded and released, first on vinyl and later on cassette and CD. His East Meets West recording with violinist Yehudi Menuhin is essential listening for anyone interested in classical music. He played with American folk and rock musicians, and made music for films. When he created music, mixing Indian instruments with early synthesiser sounds, it came out in the playfully titled album West Eats Meat. Composer Philip Glass says his own approach to music changed after he worked with Ravi Shankar, and what he created came to be known as minimalism.

Raga Mala showcases Ravi Shankar as a mix of two cultures; he was Indian enough to be outraged that rock musicians like Jimi Hendrix could stomp on their instruments and set them on fire, and at the same time, Western enough to speak openly about his private life. He refers to his two marriages and many ‘torrid’ affairs, his emotional dilemmas, a suicide attempt, his faith in babas and yogis, his love of cognac and wine, and his brief encounter with drugs and subsequent campaign against substance intoxication — all without much ado. Indian classical musicians are notorious for guarding their saintly reputations; Ravi Shankar speaks with rare candour.

Who’s the greatest?

A question is often asked about who the greatest sitarist of our times was: Ravi Shankar or Ustad Vilayat Khan? It is a question that will perhaps be debated forever, but one that dates back to 1952, in Delhi, when an acrimonious battle took place between them.

Vilayat Khan made a surprise appearance and seemingly challenged Ravi Shankar to a duel. It didn’t end well, with Vilayat Khan clinching it by gliding a small oil container across the frets to create an audacious flourish. Baba Allauddin Khan, Ravi Shankar’s guru, was furious. Namita Devidayal, in her book The Sixth String of Vilayat Khan, says the two sitarists later met over tea and samosas and decided never to play together again.

In the early 2000s, I got an opportunity to meet Vilayat Khan for an interview at the Windsor Manor, and I asked him why he had famously declined the Padma Vibhushan, calling it an ‘insult.’ By all accounts, he was upset Ravi Shankar had bagged all the big titles before him. Vilayat Khan didn’t mention his illustrious rival, and instead spoke despairingly of a decline in governmental interest in the arts. “Why should I receive an award from the hands of someone who knows nothing about my music?” he said, sitting cross-legged on the carpet in his suite.

He went on to speak about Mysuru with fondness, and said he would have been happy to receive any award from Jayachamarajendra Wadiyar, the maharaja with a taste for Indian and European music, or the Nizam of Hyderabad. The generosity of the Mysuru court, he said, had helped classical music flourish, and he described Veena Venkatagiriyappa from that city as his hero. Clearly, he was uncomfortable with what democracy had done to music patronage. Ravi Shankar, on the other hand, did not hesitate to walk through the shiny new swivelling doors he chanced upon, even when he had no idea what the other side might hold.

Unlike Ravi Shankar, Vilayat Khan wasn’t one for collaborations, even of the sort that involved the greatest exponents of two classical disciplines. “You can play Raga Chandni Kedar. Or you can play the Moonlight Sonata. You can’t do both at the same time,” he said during the interview.

Last concert in Bengaluru

In February 2012, Ravi Shankar performed at the Palace Grounds in Bengaluru, just a week or so after a German film orchestra had, with little inspiration, played the film background scores (not just songs) of A R Rahman. Ravi Shankar’s hands flew over the frets with the dexterity that had dazzled the world, but his touch had become faint, and many of his expressions sounded muted. His daughter Anoushka took off from where he left, and produced the intricate patterns and sparkling sonics that he had in his head. A classical maestro in his declining years had more excitement on offer than a full-fledged, accomplished film orchestra!

The most amused comparison of the two sitar maestros comes from Osho, a showman among gurus if ever there was one. He said of Ravi Shankar: “He has everything one can imagine; the personality of a singer, the mastery of his instrument, and the gift of innovation, which is rare in classical musicians…. Innovators are a little mad, that’s why they are capable of innovation.” Osho believed Ravi Shankar had a magical touch, and Vilayat Khan was as great because he wouldn’t allow anything to be polluted, or made ‘pop’.

Ravi Shankar’s birth centenary reminds the world how he created warmth and friendship between cultures and civilisations that wouldn’t otherwise have been able to comprehend each other.

'Ravi Shankar spells magic everywhere'

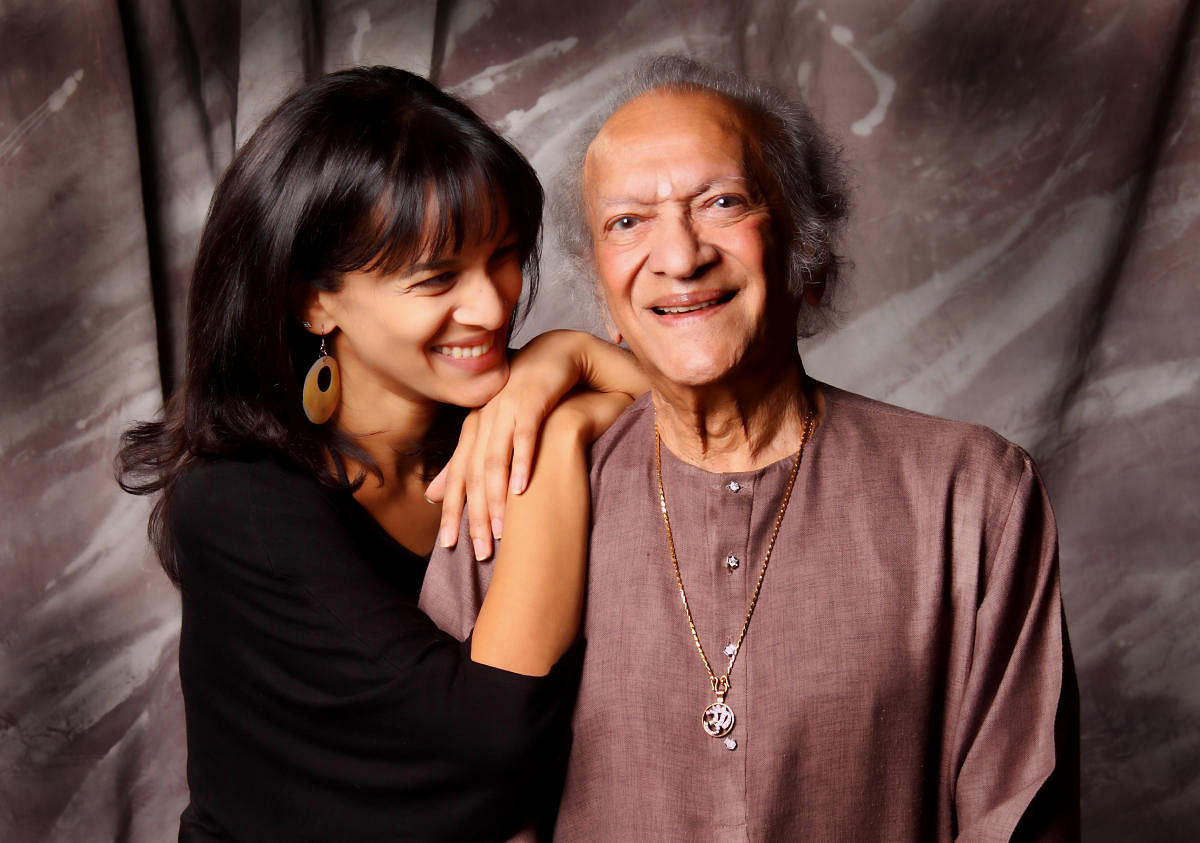

Sukanya Shankar, wife of Ravi Shankar, visited the Indian Music Experience museum in Bengaluru, just before the pandemic broke out. She has contributed memorabilia to it, including the maestro's instruments, clothes and awards, as well as his lifetime achievement Grammy. "It gives a beautiful glimpse into the life and music of Ravi Shankar," she told DHoS in an email interview. "I was so excited and amazed at the display, so people who haven't seen any of it will find it such a treat."

How did meeting and marrying Ravi Shankar change your perception of music?

I could play the tanpura, but when I first heard him I didn’t understand much of the Hindustani music that he was playing, though I was impressed. I was close to his sister-in-law Lakshmi Shankar. Her daughter Viji was my friend. When I was in London, she asked if I could play tanpura for him at the Royal Albert Hall and, of course, I was so excited. I will never forget the image of him walking down the stairs, this absolutely gorgeous creature called Ravi Shankar! I was just 17 then. Later on, as I learnt more about him, I understood that he put India on the map for many people. He has changed many lives for the better. He has made a platform for several musicians to go and perform now. Today, anybody can become famous with social media and self-promotion, but he was a household name even then, without any of this.

How has the pandemic changed your plans for his birth centenary?

Even though I am not tech-savvy, I really liked the idea of paying a digital tribute to him. I was overwhelmed by all the messages and videos. Disciples and musicians from across the world sent music in his name. Anoushka arranged and performed one of Guruji's pieces with a few disciples, and it was beautiful. Norah (Jones) sang one of his compositions, which was beautiful and heart-wrenching.

Do you plan to write about your life with the maestro?

No plans as of now, but you never know.

'He passed on the torch to me in Bengaluru'

What are your fondest memories of learning from and travelling with your father? What do you remember of the 2012 concert in Bengaluru, which turned out to be one of his last?

There’s a lot, as far as what I’ve taken from my dad, but his work ethic and discipline on stage is something I still look to follow. The Bengaluru show in 2012 will always remain special, as I could feel him passing on the torch. It was a great learning for me, because he was relying on me a little more. He would play half a line and I would need to be able to catch it and play something that made sense, authentically. He would also do this on purpose to challenge me.

How do you plan to carry his legacy of collaboration forward?

I can never express my gratitude for what I was given by my father, as it shapes everything I do and is within all the music I make. His legacy as a musician continues to blow me away. I don’t know if we all truly understand exactly how much he did for music, and for Indian music in particular. I recently featured in the Dalai Lama’s debut album, ‘Inner World’ and I’ve collaborated with American artist Patti Smith on her next album.

Tell us about the centenary celebrations, and what admirers of your father’s music can look forward to in the years to come. Are there any books, archival releases in the offing?

Apart from the digital tribute we had planned with his students for the centennial birthday (in April), Oliver Craske has just released the biography ‘Indian Sun’. I’m so glad that he’s getting rave press reviews. I’ve recently dropped the music video of my track ‘Those Words’ from my latest EP, Love Letters. It was a different experience as (dancer) Ayanna, (singer) Shilpa and I shot it virtually from our homes.