“But in coming years, he mused, we will need to defend against the assaults of nature. Disappearing glaciers. Flash floods. Droughts. Food shortage. Outmigration. A multitude of assaults that are often clubbed under the common rubric: climate change.”

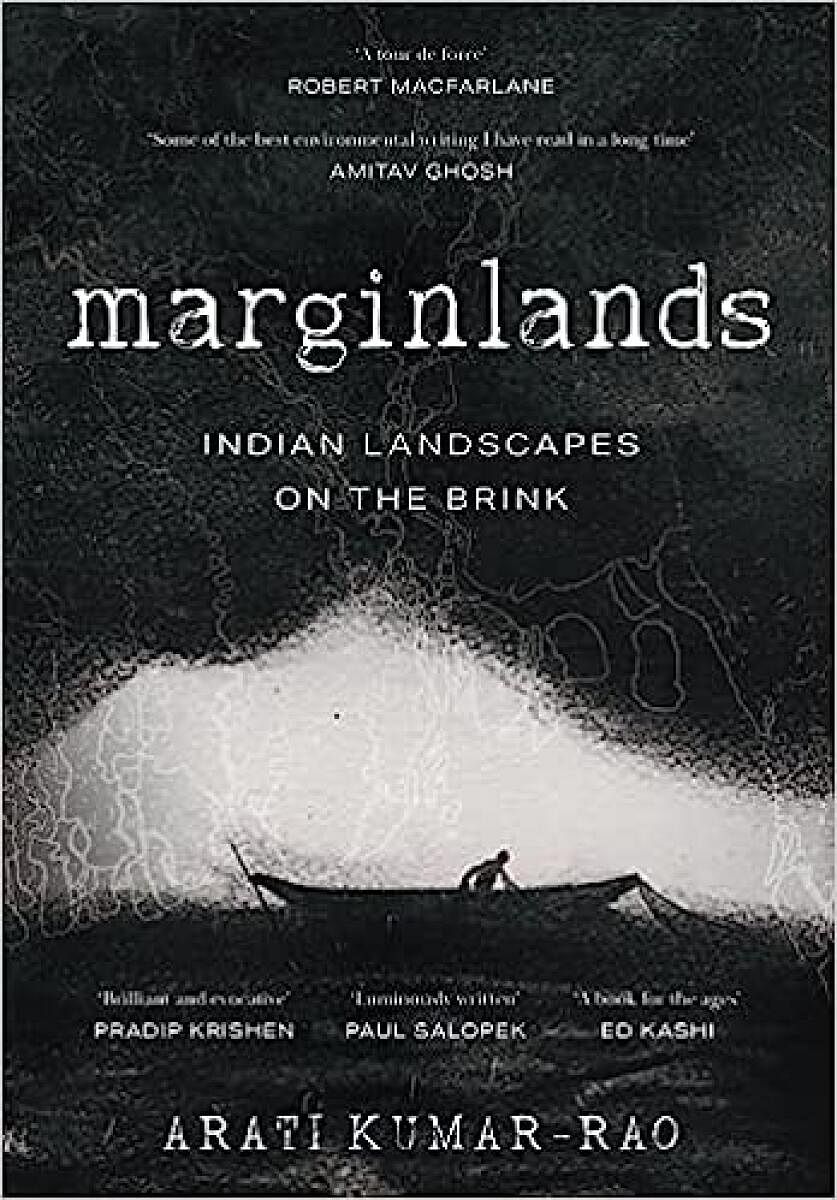

Arati Kumar Rao’s timely book Marginlands: Indian Landscapes on the Brink comes as a warning in a world that’s riddled with too many difficulties. These problems are not specific to an individual — not something that a self-help book can guide you through. They overlap and intersect to the extent that gave me nightmares of a world sinking into the water. That is the hold Rao’s book can have on a reader/inhabitant of the contemporary world.

After leaving a corporate job, Rao began her environmental writing journey with not much hope. The only things that carried her through the deserts, waters and icy environs of India were her depleting savings, assurances from a few and the kindness of those she met on her travels. The author takes us around the different habitats of the country as she learns about the everyday joys and struggles of making life possible in these regions. In the northwestern Thar desert, we are made to witness how mining has disrupted the ecosystem of the desert. Along the rivers emptying into the Bay of Bengal, the author recounts in detail her experiences with the mangroves, the music while casting a net, the allure of dolphins and the rising level of water causing displacement. In Ladakh, there is a stupa made of ice as the glaciers disappear and the looming threat of another flood haunts its inhabitants.

Taking away the tourist’s lens, through Rao and the inhabitant’s perspectives, we are able to see Thar, Sundarbans, and Ladakh in a wholly new light. The anthropogenic stories through which Rao weaves her analysis of the debilitating environment are a fitting answer to many scholarly critiques of human-nature relationships. The death of one inevitably leads to the demise of the other.

Nature is given its meaning through human presence and engagement. Humans make it a part of the culture by negotiating life alongside tigers, dolphins, vultures, mangroves, clouds, silted rivers, glaciers, wolves and urchins. Rao disjuncts the binary and offers a moving tale on both nature and cultures that have begun to disappear as these interactions lessen over time.

Among the several vignettes Rao writes about, the most memorable are those from her experiences in the watery lands of Sundarbans. From the tragic boat ride to catch fish to the dangers of a tiger waiting to claim prey, Rao’s writing is at its peak in these chapters.

Her richly intense writing doesn’t make the reader want pictures or illustrations but their presence only adds to the imagination already created in the readers’ minds. The tale of ‘tiger widows’ (women whose husbands have died because of tiger attacks in the mangroves) is perhaps a startling instance of how deeply culture has coalesced with its environmental surroundings. None is possible without the other in corners where “belief cut across religious divisions; Hindus and Muslims alike are devoted to Bonbibi.” Thus making the concern over its brink an urgent cry!

‘There are no fish’

The book is bound to make the reader feel its stories rather than simply grab it as information on India’s changing environment. In thoughtfully descriptive lines like, “They whoosh and arc and dip and sigh. There are no fish for them or us”, Rao communicates the hopelessness of a dying world. The use of present tense throughout her text as she traverses through these landscapes is immersive. It makes the reader experience the journey with her.

While Rao’s ethnographic excellence serves as an important catalogue of information, her methodology required more tightening to tie the loose knots. For instance, in the prologue, we are given a glimpse of the author’s childhood and transition to becoming an environmental journalist. However, that doesn’t develop further in the later chapters. Did her social location as an urban Hindu (by name, at least) woman affect her interaction with people across the country? What were some of the logistical concerns, relating to language especially, that she must have faced?

Rao’s book is a marvellous treatise on life on the margins, on cultures on the brink and on the disappearance awaiting the ecosystems. It is a lesson and at the same time a heartfelt tribute to India’s diverse ecology. For the reader, there is an awareness of both despair and hope. What has urban development done to communities existing on these margins? To what extent are we prepared to face the impending changes? Can those in cities make a resonant impact in their everyday lives? These questions that arise out of Rao’s writing make the search for an answer a global emergency.