The opening up of the Indian economy in 1991 by the Narasimha Rao government was transformational and irreversible. Though the economic reforms were thanks to a dire financial crisis and a looming default on international debt repayment, the new initiatives changed the face of India. Ably assisted by Finance Minister Manmohan Singh, the reforms laid the foundation for rapid economic growth. But Rao found selling reforms to the public and his own party a tough task.

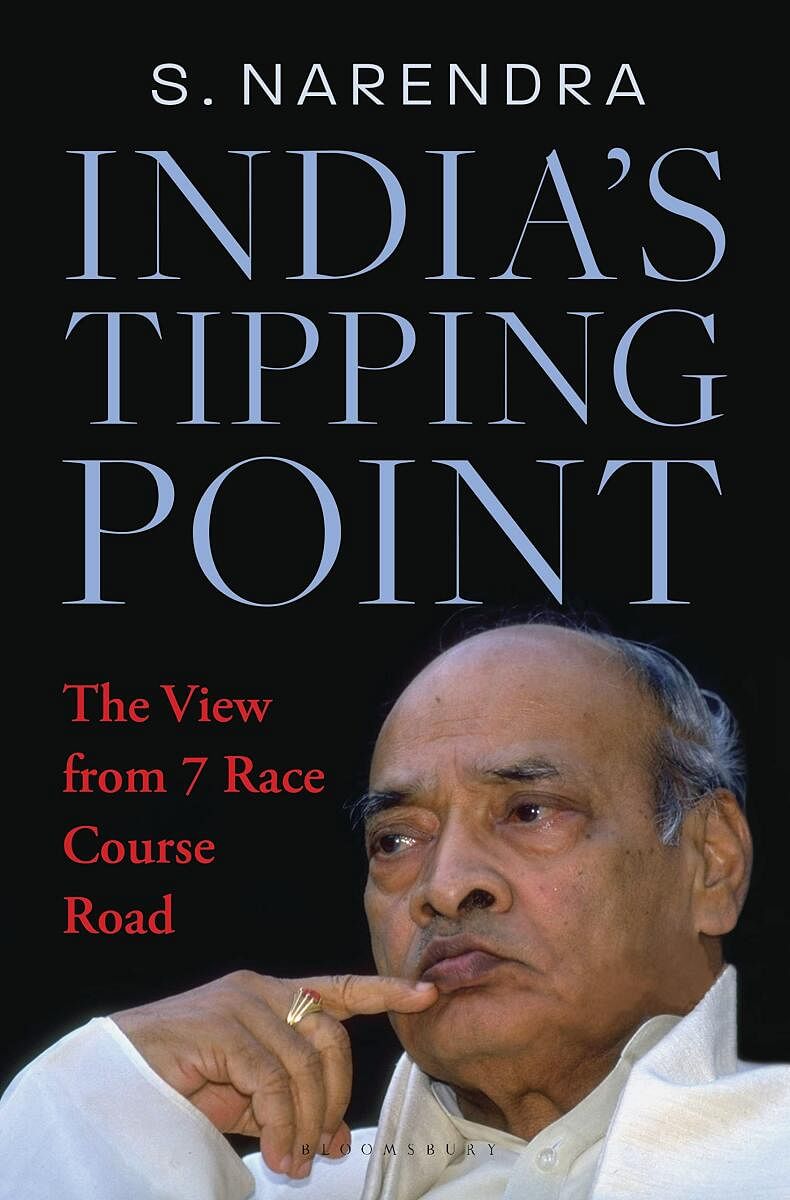

India’s Tipping Point: The View From 7 Race Course Road is an insider’s account of Rao’s tenure as the Prime Minister. Author S Narendra, as the information advisor and spokesperson of the PM, was at a vantage point, privy to crucial policy decisions. His account of the years, primarily sympathetic to his boss, focuses mainly on economic reforms and positive foreign policy initiatives. Though Rao’s stint was mired in controversies and scandals, these get scant attention. There is no mention of the shady godman Chandraswami, the PM’s spiritual advisor who was involved in multiple scams.

Narasimha Rao’s legacy is defined by the destruction of Babri Masjid on December 6, 1992. Narendra does not see any lapse on the part of the PM and is content to recount the many rounds of meaningless talks. He only repeats Rao’s sense of being betrayed by BJP leaders and having been made a scapegoat. Was he so naïve to fully trust BJP leaders? He also relies on technical arguments of the Liberhan Commission report that the Constitution is inadequate to meet such a situation. The PM had all the powers to take over the Babri Masjid and use armed forces to control the frenzied mob, if he so wanted. The death dance that followed claiming thousands of lives could have been averted. The BJP was working to a definite plan; only the Centre was caught napping.

Rao was an astute politician who could survive five years in office heading a minority government. He used to seek inputs from various sources on everything. That he didn’t see through BJP’s game plan in Ayodhya is baffling. The only conclusion one can draw is that the PM was complicit in the illegal act. In the end, he turned out to be a facilitator in advancing the agenda of the Sangh Parivar and normalising the use of hate and violence for communal consolidation. Narendra’s only regret is that the events slowed down the reforms.

He gives a candid account of the new foreign policy direction taken by Rao such as adding a business dimension to ties with the US, reshaping relations with East Asian nations and overtures to China. Rao had a good equation with Lee Kuan Yew. Narendra says the Middle East airline lobby in India scuttled the launch of the Tata Singapore Airlines venture. He shares the widely held belief that the PM had to abort nuclear tests under US pressure, but the credit went to the Vajpayee government.

Narendra disputes the widespread perception that Rao was indecisive as a leader. He used to deliberate a lot before taking decisions. The book offers glimpses of internal feuds in the Congress and Rao’s rivalry with Arjun Singh. His resignation made the PM politically vulnerable. P Chidambaram was the key link between the PM and Sonia Gandhi. The author is cagey about the Rao-Sonia relationship that later turned frosty.

He was the only former Prime Minister to appear in court to defend himself in a corruption case. The infamous stock market scam involving Harshad Mehta was a milestone in burgeoning financial corruption. He had accused the PM of taking Rs 1 crore as a bribe from him.

Undermining the electoral process, Rao made political horse-trading a legitimate tactic to survive the floor test in parliament. The JMM bribery case haunted him even after demitting office. He was charge-sheeted and convicted by the trial court but acquitted by the High Court. Other scams that hit the headlines were the Jain Hawala diary case on kickbacks to politicians, sugar import and fertiliser import scams. Rao was reluctant to act against tainted ministers “putting a cloud on the persona of PM.”

Never had amoral politics found such legitimacy. While recalling instances of “politics prevailing over prudence and probity” Narendra says: “Such instances went on to erode the moral standing of the PM and his government.” Rarely critical, he identifies a fatal flaw in Rao’s character like a hero in a Greek tragedy.

Narendra could have been more forthcoming as someone in the innermost circle of power. He has instead played safe by being selective in his approach, thus losing an opportunity to delve deep into the goings-on at the top. Nevertheless, this well-written volume is engaging.