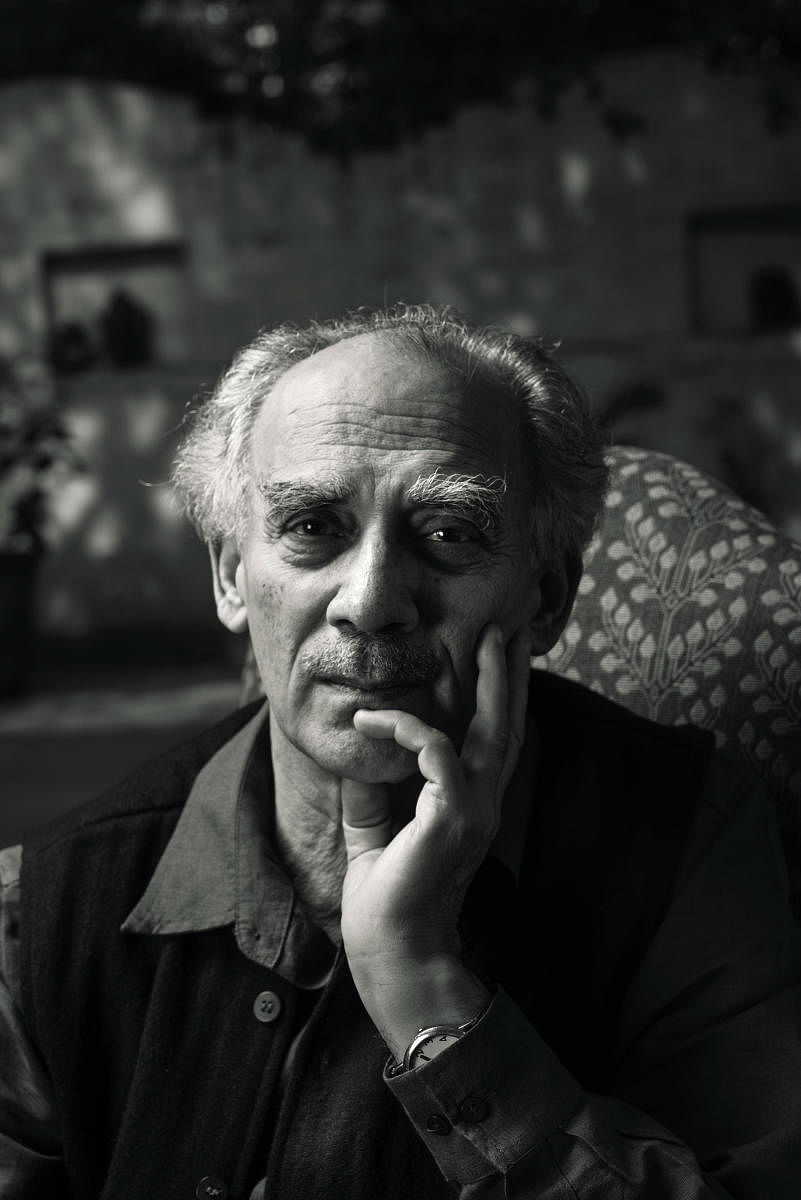

In his powerful memoir ‘Walden’, Henry David Thoreau says: “Rather than love, than money, than fame, give me truth’’. That sort of truth is neither easy nor simple and demands a lifetime of pursuit. Not many have lived this aphorism as deeply as Arun Shourie has. Writer, scholar, trailblazing editor and former minister, Shourie has been a much-admired as well as a much-vilified hero. But even his harshest detractors cannot deny that Shourie remains one of the few journalists who has relentlessly fought for truth, shaking democratic institutions, unseating politicians and unravelling corruption in the process. Excerpts from an interview

If you reevaluate your career, how much of a rollercoaster ride was it?

It was not a rollercoaster. I liked doing those things, I liked being in the government, and I like writing books, so it was not up and down.

The anecdote with which you begin the book, striking as it is, on how ‘Express’ proprietor Ramnath Goenka walked into your small cabin and told you that he was going to hang a board outside which said ‘The Commissioner for Lost Causes’... what made him say that and would you agree that the causes you fought for were not ‘lost’ ones?

Actually, that was not his perception as I mention (in the book). It was his way of paying a compliment. That was how he used to do it — a backhanded compliment. It was sort of an affectionate thing to say. And, you know, on lost causes...whose causes have not been lost? We are nobodies. Gandhiji is gone, I don’t think India is what he would have wanted it to be, Jesus was crucified, the Buddha is gone and we still cannot control our minds. But the causes, one way or the other, depend on all of us. The only causes which I would have liked to see fructify are treatments for Cerebral Palsy, which my son has, and Parkinson’s, which my wife has had for 30 years — causes which unfortunately in my lifetime would not have been conquered.

As the Editor of The Indian Express, you and your team fought corruption tooth and nail, unearthed buried issues, and shook democratic institutions. Was it easier then to get the reports published? How tough would it be now?

The whole thing has changed completely. Then, we were able to do all this only because of Ramnath Goenka. It is always difficult to get information but very often others helped, people in the government helped, people in the Opposition helped, conscientious civil servants helped. But today, there is such an atmosphere of fear that neither the owners nor the editors seem to want to take any risk. In fact, they have rationalised it that “we are not in the news business, we are in infotainment, advertising.” There is not that passion for public affairs and that is why governments have such an easy ride. This is ruinous. First of all, it has already ruined the media, it will help ruin the country also without a doubt.

The series of reports that came out while you were the Editor and while some of us were still in schools and colleges are etched in the minds of most Indians — series on Kamala, Bhagalpur blindings, and A R Antulay case, among others. How do you look at investigative journalism today? Do you think it has lost its sting?

All those stories were done by young reporters and I was just the enabler, their shield. Maybe, I would have suggested some ideas and ensured that they would pursue them for months. Today, what is happening is that people are just sitting in Delhi or in metropolitan cities; they are not going out. The account I have given of Arun Sinha’s reporting of Bhagalpur blindings — he was not sitting in his house in Patna and doing the work. He was in the jails, meeting the prisoners, doctors and lawyers who had taken up their cases and getting information from here and there. Similarly, the story on the sale of women. Ashwini (Sarin) went out and actually purchased the woman and she was delivered to him in Delhi. This business of not going out is a great drawback. I don’t know why this is the case. I am for more reporting and less commentary. Commentaries are useless.

When it comes to free speech and civil liberties, be it in the media or other platforms, how have they changed over the decades, say from the 70s? What are the challenges now?

There are several challenges on all sides. The governments have no reticence or remorse or shame at all about the suppression of civil liberties or suppression of anybody. Or putting agencies after anybody whom they do not fancy or who does not do their bidding. There should be institutional support for civil liberties, say from the courts. You can’t have freedom of speech and young reporters taking risks if the judges are going to lose themselves in a morass of legalese. If everybody works together, then the fundamental rights in the Constitution and the institutional safeguards will work, otherwise, they won’t work.

The book is full of anecdotes about your experiences with many colourful politicians, like Giani Zail Singh and Devilal. Any particular one you would like to narrate?

There were many other incidents and interactions I could have written about but this book was already running to 600 pages. One of which was my interaction with Gundu Rao, which I am sure he did not like. It was a most interesting lunch and I wrote about it. At the lunch, he had told me Mrs Gandhi trusted him a lot. I had asked him: ‘why did she trust you?’ and he had replied: ‘she can give me the keys and go to sleep.’ Editor Nihal Singh refused to publish it and said it was a private conversation. M J Akbar published it in Sunday — a fusillade followed with all sorts of high and mighty opinions about the right to privacy and so on.

Was your entry into politics a natural progression? What was it that egged you on to be part of the government?

When you receive a big jolt or derailment, it’s time to get on to some other route. We should not pine for what has gone out of our hands. I was again removed from The Indian Express and I was just sitting at home reading books, writing books. Therefore, in the last chapter, I have described a call from Mr Kushabau Thakre inviting me to join the BJP, and in the same way, I was made part of the government. These are happy accidents. I do not distinguish much between being a journalist and being in government or anything. The work is the same. I do not see it as a very big change as others see it. When I was in the Express, they said I was not a journalist, ‘he’s a pamphleteer’. When I was in the government, they kept saying ‘he’s not a politician’.

I recall one of these exchanges; a good lesson for all of us. I was in a queue at an airport for a security check when I was a minister in Mr Vajpayee’s government. I did not like to take any ministerial route. In those days, there were no metal detectors. They would pat you down to see that you have nothing concealed. When my turn came, a security constable started patting me and his boss standing behind him, accosted him in a raised voice: ‘’chodo chodo, woh minister hain’’. This policeman turned to his boss and said ‘’yeh minister hain? Arey nahin nahin, yeh minister nahin hain. Yeh Arun Shourie hain’’. Then he told me, ‘’hamesha yaad rakhna hamare liye aap ke pehchan ministry shinistry nahin hai. Aapki pehchan ek lekhak ki hai. Jab hum college me the, hum aapke articles padthe the.”

You mention “I almost continuously read Gandhiji’s writings, Narhari Parekh’s volumes about Sardar Patel, Tendulkar’s volumes about Gandhiji and reformers like Swami Dayananda and Sree Narayana Guru”. What, in these great minds, especially Narayana Guru, inspired you?

I read about Narayana Guru when I was working on a book on Dr Ambedkar. Dr Ambedkar was a very fine scholar and he certainly believed in what he was doing. I do not share the general premise of the cause that he had taken up -- he aligned with the British for that purpose. During the Quit India Movement in 1942, he was part of the Viceroy’s Council as a member. In today’s terminology, he was a minister. His anger and angry words did contrast completely with Narayana Guru’s way of taking up that cause — of making a difference in the lives of millions of people. So I was greatly attracted to him. I see his efforts at reforms, which I feel are much more consequential — that kind of good will lasts for ages. Dr Ambedkar’s approach has led to, let’s say, Ms Mayawati’s politics in UP.

Are you enjoying life away from politics...being an observer, and writing book after book?

Our enjoyments are episodic and few and far between. The condition of our son and my wife... she was in the ICU, and at one stage, she had to be put on the ventilator. Every single day, it was “pata nahin what will happen today”.

There’s a wonderful book by Albert Camus, you may remember, on ‘The Myth of Sisyphus’. Sisyphus was cursed to take a boulder up the hill and then see it roll down again. He spent his life doing that. But Camus speaks about one little moment of celebration. When Sisyphus has taken this huge rock up to the top, in that one brief moment before it starts rolling down, he exhales, thinking that he has got that tiny moment. Our good days are like that.

Is there a personal memoir in the works, perhaps stories of Adit(son) and Anita (wife)?

I had written a book called ‘Does He Know a Mother’s Heart?’ about the question of suffering and why I find the explanations in the standard religions to be unsatisfactory — also why I turned to the teachings of the Buddha. And it’s a matter of very great joy for me that Professor Amartya Sen, having read it, sent an email to me saying that it is “...one of the best books I know — moving, persuasive and very far-reaching.”

The Commissioner For Lost Causes by Arun Shourie has been published by Penguin Viking.