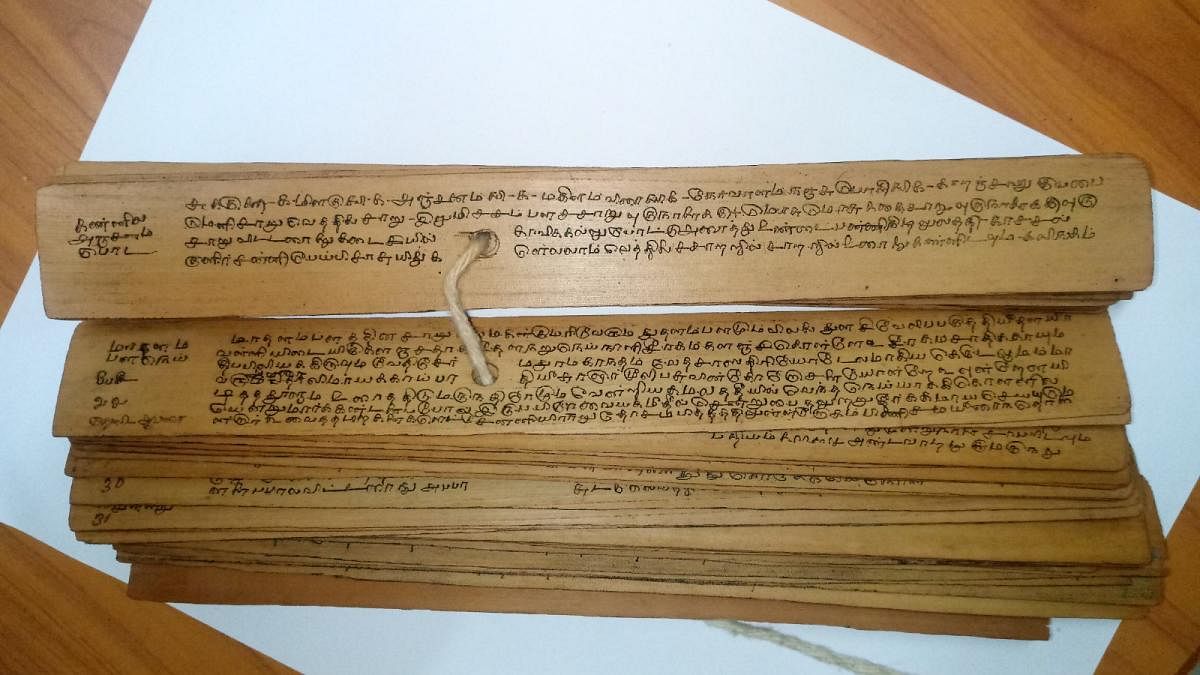

Sometimes, a single leaf can make a world of difference... if it happens to be an ancient palm-leaf manuscript. Some of these ancient palm-leaf manuscripts tell us about the past, about ancient sciences and healing tenets, systems of governance, history, and much more.

An epochal initiative is quietly happening in a nondescript lane in Chennai. Picture the knowledge of Siddhars, the ancient healers and seers of this country. They postulated amazing medical remedies that have stood the test of time, by the power of their intellect, intuition and experience. Their knowledge was once shared through cryptic verses orally, chiselled as inscriptions on stone, such as at Kanchipuram Varadarajar Temple that describes the ancient Pallava hospital system and medicines. During the great Rajaraja Chola’s period, his sister Kundavai is known to have run ‘Aadhoora Saalai Hospitals’ and details on the grants for such hospitals come to light from stone inscriptions in Thirumukkudal.

Later, they came to be inscribed on copper plates or cheppu pathiram and scrolls, though the scrolls didn’t really catch on. With the arrival of the palm-leaf manuscripts though, there was virtually an explosion in knowledge dissemination as it became quicker and easier to inscribe copies of these verses on treated palm leaves and share them around.

With a history of 700 years

Palm-leaf manuscripts were in vogue for over 700 years until the advent of paper in the 19th century. “In India, the vast majority of palm-leaf manuscripts, up to 80-90% of them, is either located in Tamil Nadu or in Tamil script, and this includes texts on medical knowledge such as disease classification, clinical features, use of plants, preparation of medicines, etc,” says Dr T Thirunarayanan, Siddha physician, academician and scientist, and the secretary of Centre for Traditional Medicine and Research (CTMR), author of several books, member of various government committees on medicinal plants and public health intervention, and a senior member of Ayurveda, Siddha Unani Drug Technical Advisory Board of Govt. of India. CTMR has embarked upon the crucial task of cataloguing and digitising these Siddha manuscripts for posterity.

There are several references in Sangam Tamil literature about Siddha medicine, texts like the Silappatikaram and Sangam-age records reveal that those ages saw the existence of people whose profession was copywriting palm-leaf manuscripts, and people had names like ‘maruthuavam’ Damodararanar (maruthavam meaning medicine in Tamil).

Some of these palm-leaf manuscripts have found safe havens in places such as the Oriental Manuscript Library at the University of Madras, Trivandrum library at Thanjavur Tamil University, and U Ve Swaminatha Iyer Library at Kalakshetra. “Who can forget the great freedom fighter U V Swaminathan Iyer, who walked tirelessly through villages, to beg, borrow, and retrieve palm-leaf manuscripts, and made it possible for us to access so many ancient manuscripts?” he points out.

Saiva mutts and many Tamil Jain families, too, have palm-manuscript collections, as they have the tradition of celebrating ‘patra dhana’, or ‘knowledge sharing’ by copying the manuscripts and distributing them.

While so many priceless palm-leaf manuscripts have been ferried away by invaders, it is also true that so many invaluable palm-leaf manuscripts that had been passed down generations of traditional healers now lie disregarded and uncared for ever since traditional healers took to other professions. So, CTMR took upon itself the task of collecting, restoring, cataloguing and digitising these priceless ancient palm-leaf manuscripts.

“We focus on manuscripts with individual healers or families of the healers. They often hold manuscripts without understanding or knowing what the manuscripts are about. Individual healers have been reduced to utter poverty ever since the Indian Medical Central Council Act, 1970, that regulates traditional medical practices remove the legal sanction for traditional healers to practice. With this, eventually, the traditional healers lost the incentive to learn or even care for the knowledge of their forefathers had carefully guarded and passed down generation through generation,” Dr Thirunarayanan rues. A beautiful and proven chain of ancient knowledge and healing system has been lost thus, with the baby thrown out with the bathwater.

Certified process

What holds a ray of hope is the 2017 move of the Quality Council of India sanctioning the practice of ‘traditional community healthcare providers’. Traditional healers can obtain this certification and practice legally the speciality they have been certified for across India. It is an elaborate, stringent and standard system of certification. These healers, after certification, are legally and scientifically authorised to handle specific issues like arthritis, jaundice, bone setting, etc.

For Dr Thirunarayanan and his colleagues, it is always thrilling to come across an ancient palm-leaf manuscript. It could be a copy of the original, repeatedly copied, or a rare or one-of-its-kind manuscript. CTMR has come across some original texts that have never been in print before. Such as the agathiar gunapaadam that describes different types of rice, herbs, meat, marine products and documented properties of water from different sources.

CTMR’s work begins with sourcing and collecting these manuscripts, and CTMR always offers to return the restored manuscripts to the healer families, unless they prefer CTMR to keep and preserve it for posterity.

In detail

A palm-leaf manuscript is a delicate treasure and Dr Thirunarayanan and his associates handle it with reverence. They first clean it by wiping gently with a muslin cloth, then brush it gently with lemongrass and linseed oil for preservation. Most of the time, the engraving is not visible. To reveal the engraving, an extract is applied to the folios. Earlier, for this purpose, an extract from oomatha (datura) leaves and karisala elai (bhringaraj) was used. “Now, we just use activated charcoal generated from coconut shell, powder it finely, and mix it in linseed or lemongrass oil, and paint it over the manuscript. The inscriptions imbibe the ink and become visible.” It takes around six months to a year to clean, preserve, catalogue and digitise the texts using a sophisticated camera scanner.

The original order of the leaves of the manuscript that are usually numbered in Tamil numericals (ka is one, for instance) is noted. Then it is over to the Tamil scholars to describe and translate the texts as the ancient Tamil in these manuscripts sport is quite different from the contemporary Tamil in use.

The manuscripts are then scanned and these images and photographs along with the catalogued texts get stored in two or three locations in external hardware. Researchers are welcome to CTMR’s library for reference work.

In the last few years, with the GOI coming out with a standardised certification process and recognising the contribution of traditional health practitioners through the Padma awards, the knowledge gleaned by the Siddhars looks all set to shine again. Nevertheless, with much of the knowledge of the Siddhars unexplored still, CTMR’s digitising initiative is crucial. CTMR has so far collected, digitised and catalogued nearly 620 medical palm manuscript bundles, GOI funds supporting digitisation of 160 bundles and institutional/private funding for the rest. Each bundle having as few leaves or folios as just three or four or as many as 600 leaves.

Some of the incredible manuscripts that CTMR has thus digitised include texts of the singularly perceptive Siddhar Boghar in lyrical Tamil syntaxes like venpa, asiriarpa and kalipa. But the project is now faltering for lack of funds to travel and source manuscripts, restore them, digitise them using sophisticated scanners, catalogue and decode them with the expertise of

Tamil scholars.