‘If I die in combat zone,

Box me up and ship me home,

Pin my medals all over my chest,

Tell my mom I did my best’ ~ William Timothy ‘Tim’ O’Brien

Twenty five years later, the Kargil war still stands testament to the bravery and resilience of the Indian Armed Forces. Over 30,000 soldiers engaged in fierce combat against Pakistani forces on the icy and rugged terrain of Kargil to protect the sanctity of our borders. It was fought between May and July 1999.

‘Operation Vijay’ aimed to reclaim the strategic heights in the India-

administered territory that had been surreptitiously occupied. We won but the lives of over 500 soldiers were lost, their blood staining the snow. More than 1,300 were left injured.

It was India’s first televised war and the extraordinary acts of sacrifice left a deep impression on the nation’s psyche. But public memory is short-lived. Citizens don’t quite think about the price that is paid daily for their peace beyond Kargil Vijay Diwas or when news of infiltration breaks in.

This is why war hero stories are necessary — to remind us to value the freedom we have today. Hence, we have been trying to find and tell the stories of martyrs of the Kargil war. We lost over 500 soldiers, yet not many of us can recall their names beyond Capt Vikram Batra from Palampur and Capt Anuj Nayyar from Delhi.

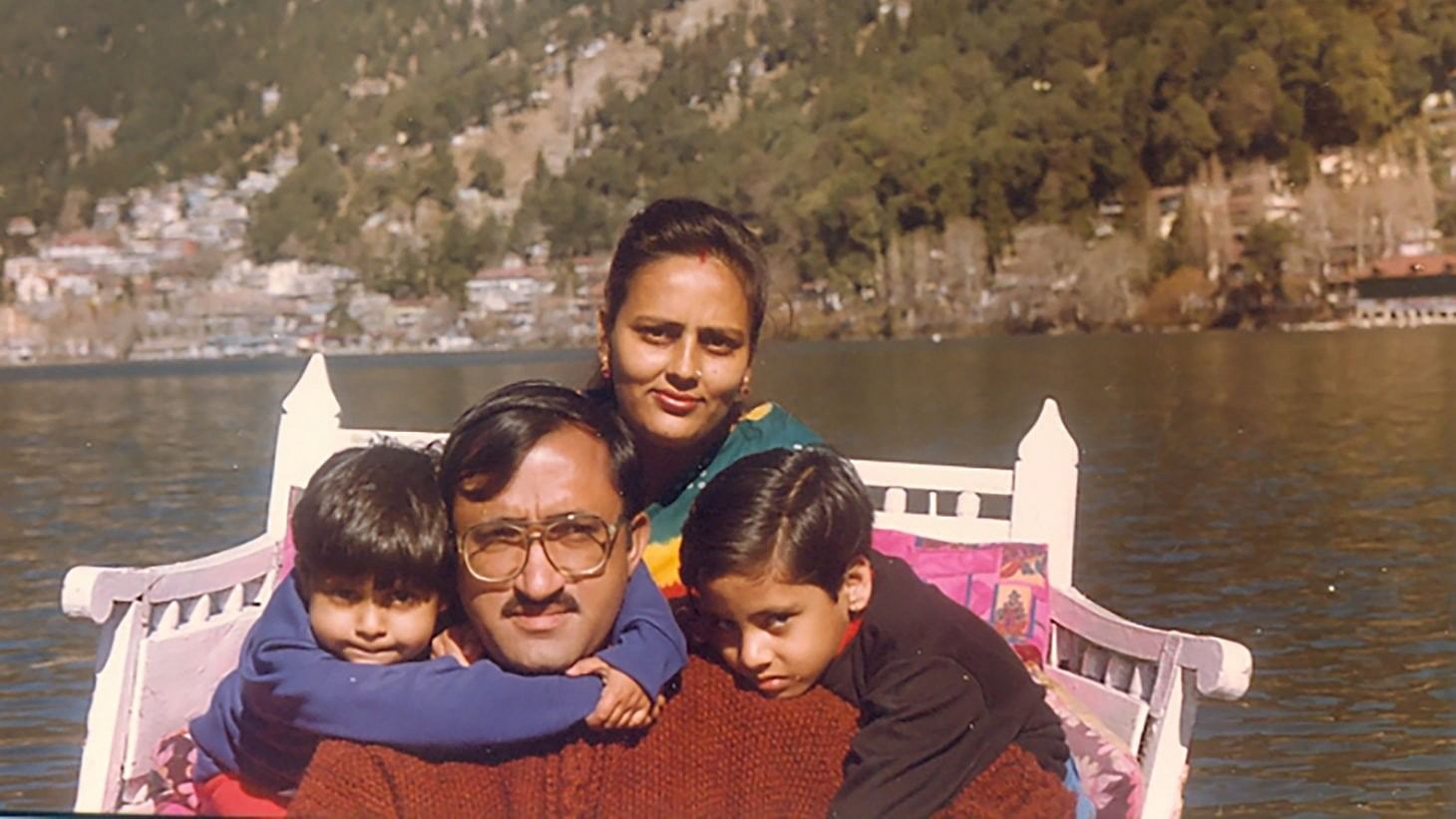

I am a doctor by profession and Diksha, an entrepreneur. It was our ‘daddy’ Maj C B Dwivedi, from the 315 Field Regiment, who set us off on this mission. He had earned a Sena Medal. Yet his name or contribution was barely mentioned in the articles and books we scoured after he got killed in action in the Kargil war. We asked ourselves, ‘Why are we waiting for others to tell our daddy’s story?’ Thus, we started our storytelling journey in 2015.

Dear daddy

Diksha took the lead. She shared the story of his martyrdom on her storytelling platform, AkkarBakkar. Titled ‘The Kargil War Hero Nobody Told You About: He’s My Father’, the tribute racked up a million views. Journalists lined up to interview us. Gurmehar Kaur, a martyr's daughter herself, messaged to say she was inspired. This was before Gurmehar went viral as a student activist. Most unexpectedly, the additional directorate general of public information called up our mother, Bhawna. And the following year, the government invited our family to attend Kargil Vijay Diwas celebrations at Drass, near Kargil. This was 18 years after our daddy laid down his life for the nation.

On the evening of July 2, 1999, our father and other officers were huddled inside a bunker in an area called Pandras when the enemy started shelling the location. He stepped out to instruct his men to take cover. In the process, his arm was pierced by the splinters of a shell. Some splinters entered his body too. They caused internal bleeding, which he did not realise. When others rushed to get him medical help, he urged them to instead focus on those who were more grievously injured. His decision saved some lives but his own did not stand a chance. In his last moments, he told one of the men from his regiment that he wanted to live for his daughters. At the time, I was 12 and Diksha, 8.

We heard different versions of our daddy’s last moments. Some made us cry, others made us angry because they were not at all in line with what we had been told before. We dug deeper with a hope to learn more about that moment and our father, whom we lost so early.

He was a feminist. He would take time off work to help us prepare for exams — math and physics especially. ‘But you don’t take leave to go on vacations’, our mother would complain. He would demonstrate how lenses and pinhole cameras worked. He loved cooking — we miss his ice lollies and sandwiches the most. He attended more parent-teacher meetings than our mother did. He loved photography. He was often missing from group photos in the regiment as he was the one clicking them. He had asked an aunt of ours to bring him a built-in zoom camera from the US. He never got to see or try it.

We are told when he was young, he saw some policemen resolving an issue in his village, Chandiha, in Bihar. That’s how his love for the uniform began.

Priya Ramani of Juggernaut Books spotted our father’s tribute piece. It spoke of letters our daddy had sent us. ‘I will see you soon’, read a letter he wrote 12 hours before he was killed. Priya made Diksha a book offer — describe the Kargil war through the letters sent by soldiers. The mobile revolution had not yet arrived. That’s how her first book, ‘Letters from Kargil’ (2017), was published.

DH illustration

Credit: Deepak Harichandan

Finding letters

Diksha tasked our mother with spreading the word that she was looking for letters and journal entries by Kargil martyrs. Meanwhile, she worked her phone, contacting journalists, army kids, army veterans and Kargil war survivors.

For Capt Nayyar’s mother, the wound had not healed. She cried as she told Diksha she hadn’t opened the box in which her son’s belongings arrived.

Charulata Acharya, wife of Maj Padmapani Acharya from Hyderabad, was in a better position to talk. During the war, when he was the ‘A’ Company Commander of 2 Rajputana Rifles, he wrote a letter to his family: “Dear Papa… don’t worry about casualties — it’s a professional hazard... Tell mamma that combat is an honour of a lifetime.”

In a fierce night-long battle, Maj Acharya’s team recaptured Tololing Top, turning the course of the war in India’s favour. This was in addition to the recapture of Tiger Hill. Despite being heavily injured and unable to move, he ordered his men to march ahead while he kept firing.

Diksha was now sitting with heaps of photocopies of letters, addressed to wives, parents, children, siblings, fiances and girlfriends. But there was a regret. Jawans were the major casualties but we could not bring out their stories. They hailed from rural belts, where people didn’t preserve letters and diaries. Was it out of grief? Our mother also burnt her letters to daddy.

I wanted to describe the Kargil war through the perspective of a martyr’s wife, our mother. But when an opportunity came my way, I developed cold feet. You see, unlike Diksha, I wasn’t a writer. In 2019, when I became more confident, thanks to social media posts and personal entries I was writing on the subject, I would pen ‘Vijyant at Kargil’ (Penguin Random House). It is a biography of Capt Vijyant Thapar, who died fighting the crucial battles of Tololing and Knoll. His father and army veteran, Rtd Col V N Thapar, was my co-author. I travelled to Chandigarh, Jhansi and Noida to meet his friends, coursemates, colleagues and cousins. Tracking down his Class 3 schoolmate, now in the US, was thrilling.

With our foot in the door of the publishing world, we now wanted to uncover more stories. We flew to Nagaland to meet the family of Capt Neikezhakuo Kengurüse, fondly known as Nimbu Saab. He led his men of the 10 Platoon of D Company into combat at 16,000 feet in -10°C temperatures, carrying a rocket launcher. He killed four enemies but he succumbed to a splinter injury in his abdomen. The 25-year-old let go of his boots as he was slipping off the cliff. His men followed suit. Along with his younger sibling Neingutoulie, Diksha and I authored his biography ‘Nimbu Saab’ (HarperCollins India). It was published last month.

Off the field

These men had so much character. Capt Saurabh Kalia, 22, and Capt Amit Bhardwaj, 27, were the first two infantry officers to meet their end on the battlefield. They were brothers in arms in 4 Jat. This was the first infantry regiment to be trusted with the job of patrolling the Line of Control to assess infiltration.

Capt Kalia, along with five jawans, was captured by Pakistani troops following a gunfight. They were held as prisoners of war and tortured to death. They suffered cigarette burns, broken teeth, pierced eardrums, chipped noses, and mutilated private parts. To this day, the Kalia family, based in Himachal Pradesh, has been urging the Indian government to intervene. Their abuse is a violation of the Geneva Convention, which lays down guidelines for the treatment of prisoners of war. Capt Kalia had joined the army a few months ago.

Capt Bhardwaj from Rajasthan was met with a shower of bullets when he went looking for his junior, Capt Kalia. On June 5, his sister Sunita Dhonkaria received a dated letter from the Indian army, stating that Capt Bhardwaj had gone missing in action. She kept the information from her family but 10 days later, the grim news was out on television news channels.

Both were first-generation army officers. An article titled ‘Kargil’s first hero’ paints an intimate portrait of Capt Kalia. His parents called him Naughty, after a nurse at the time of his birth remarked he was a naughty baby. He wanted to be a doctor but he and his school friends filled the Combined Defence Services form for a lark. It was a fun excuse to travel to Chandigarh to write the exam. He passed.

Capt Bhardwaj loved plays, quiz, table tennis and swimming. He was a fan of the gangster movie ‘The Godfather’. He wanted to do something great for the world, he wrote in his journal many times.

Maj Acharya penned sweet letters to his wife who was pregnant when he went to war. He would ask her to eat healthy, go for check-ups, read the ‘Bhagavad Gita’ to their unborn child, and avoid horror serials. He ate well but missed her food. He wished to take her around the barren but beautiful Kargil. He would also check on Kaajal, their dog.

The most viral last letter came from 22-year-old Capt Vijyant, who was from the same regiment as Maj Acharya. He was born into a military family from Punjab. As a child, he would put on his father’s army uniform and cap and walk around with a cane. He wore his patriotism on his sleeve. He wrote to his family, ‘By the time you receive this letter... I will be enjoying the hospitality of Apsaras (angels)’. ‘If you can, please come and see where the Indian Army fought for your tomorrow’, ‘Meet ***** (I loved her)’ and ‘Keep on giving Rs 50 to Ruksana per month’, he continued and signed off with ‘Live life King size’. Ruksana was a six-year-old girl from Jammu & Kashmir’s Kupwara. He had helped her regain her speech. She had lost her voice after she saw terrorists killing her father.

Capt Kengurüse also left behind instructions for his family. He had 12 siblings. He wanted them to stay together. He asked them to visit church frequently. ‘You must meet my girlfriend. I loved her’, he added. He was a teacher before he donned the olive green uniform. He was the first gazetted officer in the town of Jalukie, and he was proud of that. When he returned home on holidays, he would step out in his uniform and ask people to salute him and prefix his name with his rank. He is a local hero — ask for his address in Kohima where his family now lives and they will tell you. His siblings are into business, politics, education and music. But they say nothing they do will ever match up to his greatness. The lobby at their home is adorned with Capt Kengurüse’s medals and pictures of his grave.

The family of Capt Neikezhakuo Kenguruse with his photo

Waiting to be told

The responsibility of keeping these stories alive in public memory often falls on the family and it can be a painful task. After Maj Vivek Gupta’s sacrifice in Tololing, his father wrote to the Indian Army expressing his pride and grief. In the years after that, we saw his story disappear into oblivion. He was from Dehradun.

Capt Amit Verma came under heavy fire as he and his men from unit 9 Mahar were moving to capture an enemy bunker in the Tiger Hill area. Every time his parents visited us, they held in their eyes, an empty, unending pain of losing their only son. Their visits fell from infrequent to nil. We never heard about Capt Verma again.

Some stories return to the news cycle occasionally, such as that of Rfn Bachan Singh. His son Hitesh Kumar recounted his martyrdom at Tololing when he was commissioned as a Lieutenant in the same battalion as his father, the 2 Rajputana Rifles. The family hails from Uttar Pradesh.

We could not believe our luck when Atoulie, another of Capt Kengurüse’s brothers, told us at a Kargil Vijay Diwas function that he was looking to get his brother’s story written. We feel humbled to have become a medium to tell these stories. One thing every army family strives for, sometimes, too hard, is to make their martyred son, husband or sibling proud. We hope our daddy is proud.

Like this story? Email: dhonsat@deccanherald.co.in