From the land of Kerala, beautiful, but without opportunities, hundreds find their way to Delhi in the early sixties, yearning for a better life. It is a motley crowd of job aspirants, journalists, nurses, small traders and even call girls drawn to the city of possibilities. Soon, they realise that their mental image of the city and the reality are different. Finding a bed to sleep on, or having two square meals a day, is a luxury. Many get support from the Malayali community. A few make it big, but the great majority find it difficult to eke out a living.

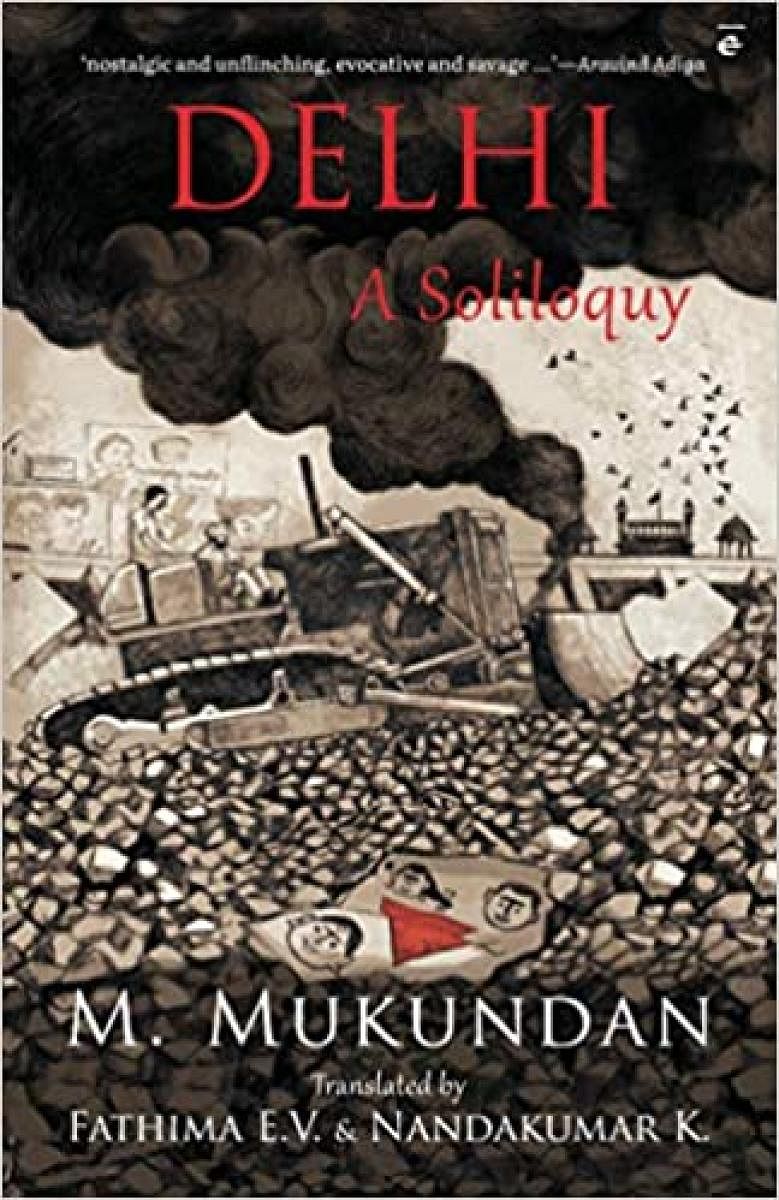

In Delhi: A Soliloquy, celebrated Malayalam novelist, M Mukundan, traces the evolution of the national capital from a poverty-ridden cluster of villages with cauliflower and wheat fields to a modern metropolis. Mukundan, who landed in Delhi in 1962, worked as a cultural attaché of the French embassy for four decades. Originally published in Malayalam as Delhi Gadhakal in 2011, the novel paints an unflattering picture of a city steeped in squalor, poverty and violence.

Mukundan, who is an astute observer of events and people, says he has grown up with Delhi as a writer. His wealth of experience, as a witness to social and political turmoil that shaped the city, provided a fertile ground for his creativity to bloom.

The story is mostly narrated through the eyes of Sahadevan, who reaches Delhi as a 20-year-old in 1959 in search of a job, only to live there well into his old age. He finds home in the family of trade union leader Shreedharanunni. His wife Devi and their children, Sathyanathan and Vidya, treat him as a family member. The news of a sudden Chinese invasion shatters Shreedharanunni, communist and a great admirer of China. Feeling betrayed, he dies of a heart attack. After his death, it is an unending struggle for Devi to bring up the two children with a meagre income.

Impact of wars

Others in Sahadevan’s circle of friends include firebrand journalist Kunhikrishnan and his wife Lalitha, maverick artist Vasu, carpenter Uttam Singh and his family and street barber Dasappan. Sahadevan has witnessed the impact of the wars of 1962, 1965 and 1971 on Delhi. He and his friends end up as victims of Emergency excesses. Midnight knocks, missing activists and journalists become routine. Kunhikrishnan disappears, only to emerge with both his arms crushed by the police. Sathyanathan is forcibly taken to a vasectomy camp and sterilised. Horrors of forced sterilisation and the ruthless demolition at Turkman Gate, rendering many homeless, bewilder Sahadevan. His own small establishment is reduced to rubble by bulldozers. But he is reluctant to pick up the pieces of his shattered life.

It is during the anti-Sikh riots after Indira Gandhi’s assassination that Sahadevan stakes his life to save Uttam Singh’s daughter Pinky from the marauding mobs. But her parents perish. Their other daughter, Jaswinder, who marries without dowry, suffers ignominy at her in-laws’ home. The family members escape leaving Jaswinder locked up in their house, which is burnt down by the rioters.

Powerful, endearing characters and their daily struggle for survival, make this novel immensely readable. Vasu is a vagabond, bohemian artist floating in his own world. It is his self-appointed promoter, Hari Lal Shukla, who makes money out of Vasu’s valued paintings. When Vasu is set on fire, mistaken as a Sikh, Shukla becomes the owner of all the paintings, worth crores.

An outsider’s view

Sahadevan lives for others, for his family members in Kerala, and for other poor people in Delhi. He is there to help anyone in need. At times, he wonders how he is stuck where he was decades ago. Sahadevan is an observer, participant and outsider. He is a dreamer for others.

He wants to help Uttam Singh realise his dream of setting up a furniture shop, but can’t. Rosily becomes a call girl to earn money for her famished family members as well as for her dowry. There is also the activist JNU student Janakikutty. Only a few characters have happy endings. Nostalgic reminiscences of the Malayali community are all-pervasive.

As a chronicler, Mukundan misses nothing related to Delhi. The canvas is Dickensian. The novelist says in an interview: “Delhi’s underbelly is laden with squalor and misery. I wanted to talk about these dark sides of the city.”

The narrative of Delhi’s slow descent into one of the most violent places on earth is scathing, incisive, and at times, brutal. Caste conflicts and communal hatred, not to mention the unbearable stench and filth, are abhorrent to a sensitive mind. Present-day Delhi scares Mukundan. He terms the city in the sixties a safer place.

It took two years for Mukundan to write the novel. But the translation took four years. Fathima and Nandakumar have deftly done their job, while retaining the spirit of the original.

Some readers may struggle with the many Hindi and French expressions (which are used without footnotes).