It wasn’t just the Romans who described it as woven winds in the 1st century. In the 7th century, the Chinese monk and cerebral traveller Xuanzang described it as “…the light vapours of dawn.” In the 13th century, Amir Khusrow, the great Sufi musician, poet and scholar, described it as the “…skin of the moon.”

The exceptional pieces were reserved for the Mughal emperors. Testing of its airy weightlessness was by drawing it through a finger-ring; it drew censure from the austere Emperor Aurangzeb (1618–1707), who is reputed to have reprimanded his daughter Princess Zebunissa for appearing inadequately dressed when she was actually draped in seven layers of the finest. Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, the 17th-century traveller, commented on its sheerness, stating “that when a man puts it on, his skin shall appear through it, as if he were naked.”

Geographical appeal

In Europe, it was worn by the doomed Empress Marie Antoinette (1755-93) and the Empress Josephine, who followed. The British, too, could not have enough of it, and in the 19th century, it was described by Edward Baines, Member of Parliament, as it “…might be thought the work of fairies, or of insects, rather than of men.”

In 1811, author Jane Austen wrote to her sister on how she succumbed to its charms “…I am getting very extravagant and spending all my money and… I have been spending yours too in a linen-draper’s shop, which I went to for check’d muslin, and for you… I was tempted by a pretty coloured muslin…”

Myths surrounded its making — the herder banished from his home as he was unable to distinguish between the grass and what appeared to be dewdrops, thus allowed his cow to graze on the precious textile. That the spinning of the yarn was best done on an anchored river boat; that a pound of this spun thread when unreeled would stretch 250 miles. That the finest weaves were produced at dawn and at dusk; and that the weaving itself was done underwater perhaps, as often the pit-loom had to be flooded to add to the humidity and prevent the fine yarn from drying out.

So, what was this cloth that so captured the imagination of the world and continued to do so over the millennia?

Derived from a species of the cotton plant Gossypium arboreum var Neglecta, locally called phuti and nurmah kappas, this plant produced the silkiest and finest cotton yarn known. Grown in the Gangetic plains of Bengal, the finest varieties were from the Dacca region (now in Bangladesh).

What lay at the heart of all this myth-making and the telling and retelling of the legends was that the cotton muslin jamdani was considered to be the rarest, the finest and the most sophisticated weave produced on the Indian loom.

These gauzy muslins were embroidered on the loom by the addition of weft threads — introduced by hand — during the weaving process, creating patterns of figures, florals and geometrics that were nuanced by light and shadow, and tones of transparency and opaqueness that lent themselves to drape and fall.

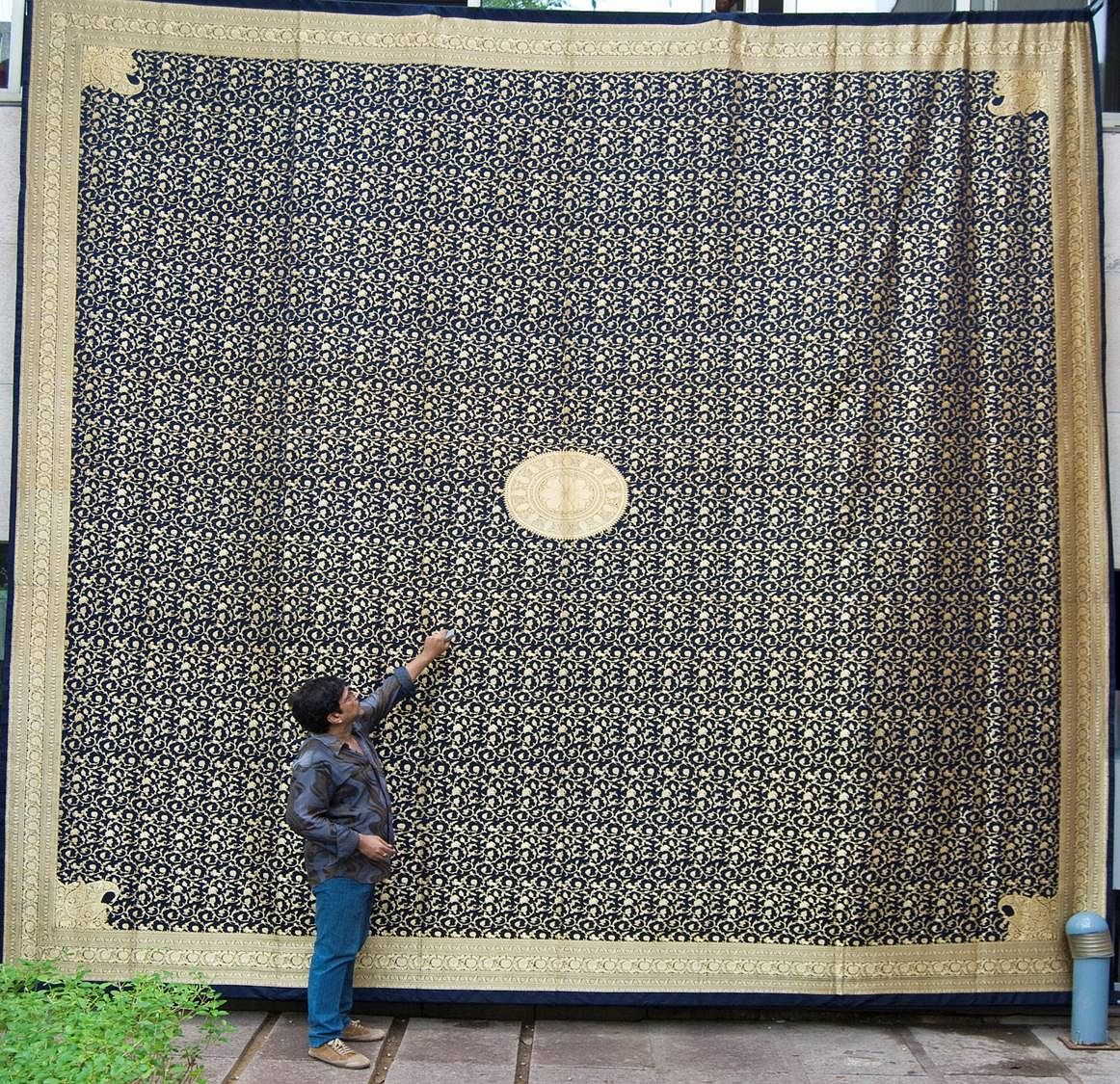

Given that weather conditions are detrimental to the preservation of such gossamer textiles, our material evidence comes from the surviving pieces dated only to the 19th century. These white-on-white jamdanis, the tone-on-tone indigo nilambari or the yellow pitambari’s, the use of contrasting colours, the zari that added gleam, the varied patterning, all created permutations and combinations that were seemingly endless.

The history of the making and the weaving of the muslin and figured jamdani from this short-stapled fine yarn was centered around the cotton growing region, with the weaving cities of Banaras and Tanda in Uttar Pradesh also playing their part . The fame of the Dacca weaves remained so ingrained in the imagination that even today, 70 years after the Partition of India, the finest muslins and jamdani produced in India continue to be called Daccai.

Who were the remarkable artistes, designers, colourists and masters of the weave who created these textiles in the past? Unfortunately, history has thrown a veil of anonymity that hides them from our gaze. However, in today’s changing landscape, this veil has been shredded and we can recognise and credit the holders of the parampara, who in their own individual way have brought this tradition forward to life. And, the seed variety of the Gossypium arboretum var Neglecta is no longer available, replaced by the predominant use of the long-staple, as standardised yarn varieties suitable for machine-textile production pockets of resistance and excellence remain.

In Bengal, the spread of national-award winning experts covers the weaving districts, and a much-truncated list includes the areas of Kalna with masters like Jyotish Debnath and Pundu Nandi.

Artists on the list

In Fulia, the list is long and includes among others Amal Basak, Biren Basak to Swapan Kumar Basak. In Dhatrigram, there is Sushant Kumar. In Nasaratpur, there is Suresh Basak and Gautam Basak.

The list is as long and as distinguished in Banaras with Peer Mohd Ansari, Mainuddin, Nazir Ahmed, Ali Rasul, Shah Mohd Ansari, Jamaluddin, Ainul Haq in Cholapur. Babulal Patel from Sajoi, Mustak Ahmed in Rasoolpura and Sribhas Suparkar from Banaras city.

The best jamdanis produced by these masters continue the tradition being sheer and fine, with their figured patterning in a minimum count of 200 to 250 with approximately 1,700 threads continuing to command their position as the finest and the most sophisticated weave produced on the Indian loom.