By Zachary R Mider and Chris Kay

An Indian drug maker blamed for the deaths of 20 children in Uzbekistan produced multiple batches of tainted cough syrup over more than a year, according to data from export records and the World Health Organization.

The WHO said this week that 21 batches of cough syrup made by Marion Biotech Ltd. were tested by Uzbek authorities and found to contain unsafe levels of two toxic chemicals. Bloomberg News identified some of these batches in separate Indian export records as having been manufactured as early as May 2021 and exported to the Central Asian nation that June. Other batches appear to have been made on more than half a dozen dates and as recently as August 2022.

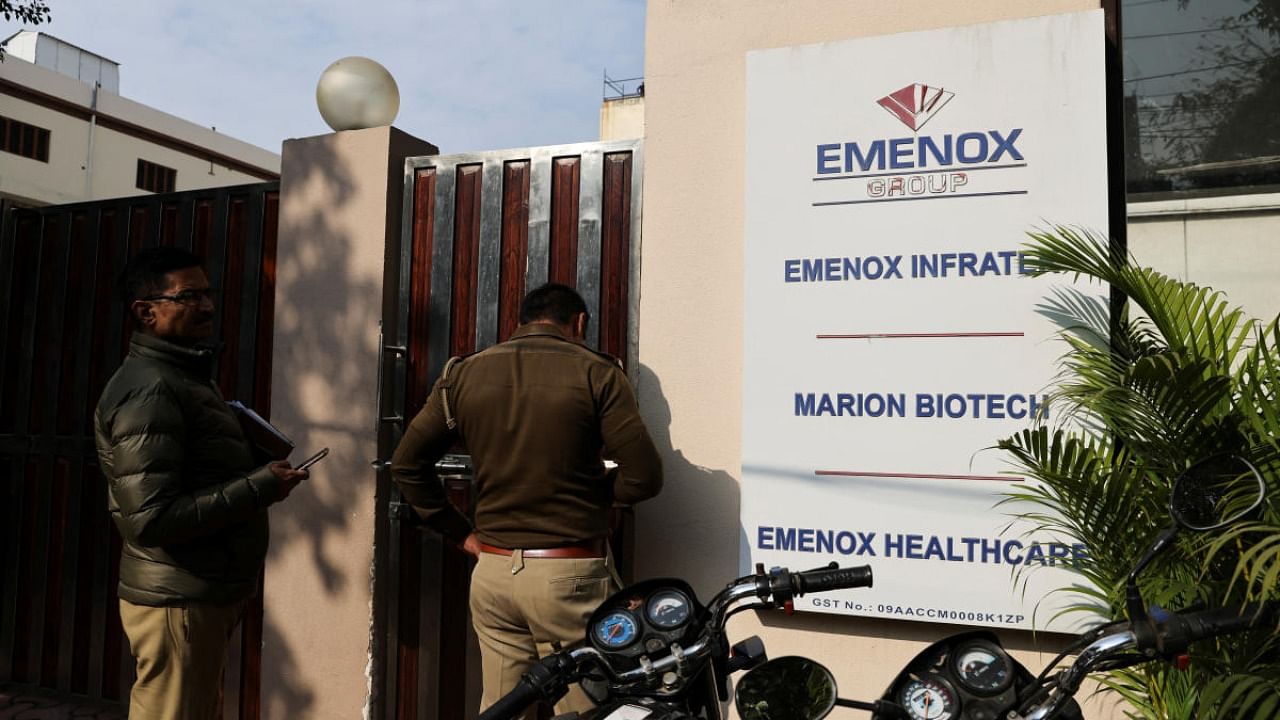

Marion said it followed safety procedures and is cooperating with Indian regulators, who have yet to release the results of their own testing of drug samples. The small drugmaker, based in Noida denied the WHO’s claim that the toxin ethylene glycol was found in its Doc-1 Max product and cast doubt on the quality of the Uzbek authorities’ investigation.

“There is something more to the deaths of the children rather than simplistically blaming it on the syrup,” the company said in an emailed statement.

The production timeline raises new questions about quality controls in pharmaceuticals sent to developing countries. At least 70 children died in Gambia last year from tainted cough syrup supplied by another Indian drugmaker, a parliamentary committee in the African nation found. And in Indonesia, tainted syrup produced by local firms killed about 200 people, mostly children, in 2022.

The records also show that Marion was shipping the same syrup product types flagged by the WHO — Doc-1 Max and Ambronol — to three other countries during the time period it was allegedly producing tainted syrup. Shipments of these products to Cambodia, Turkmenistan and Kyrgyzstan in 2022 had different batch numbers from the ones tested in Uzbekistan, the records show. The export records were provided by ImportGenius, a company that tracks global trade.

Emails to health authorities in Cambodia and Turkmenistan weren’t returned. Kyrgyzstan’s health ministry suspended sales of the Doc-1 product in December, news website 24.kg reported.

A spokesperson for the WHO said in an email that it hasn’t “formally identified” any additional countries where tainted Marion products were sent, adding, “We are aware of anecdotal reports that we are following up on with other countries.”

In India, state and central drug safety regulators conducted an inspection at Marion’s plant last month after hearing from their counterparts in Uzbekistan. Media organisations reported this month that the company’s production license was suspended. Regulators didn’t respond to requests for comment on Thursday.

Prashant Reddy T., a Hyderabad-based lawyer and co-author of The Truth Pill: The Myth of Drug Regulation in India, said Indian drug regulators are more interested in defending a powerful industry than ensuring safety. “This is very much a political problem,” he said. “Until there is a signal sent from the health minister or from the prime minister to the regulators to do a serious job, these bureaucrats are not going to do it.”

Marion said that a recall in Uzbekistan recovered only a small fraction of the bottles sold in the country, which it said indicates that “the balance have been consumed without any side effects.” The company said it wasn’t privy to the report produced by Uzbek authorities and cast doubt on the WHO’s decision to accept the findings without conducting its own testing.

“We will call upon the Uzbekistan authorities to do a thorough and informed investigation on the issues wherein views of expert pharmacologists, medical experts and forensic experts are also taken to come at a finding,” Marion said in the statement. “We are extending all our support for the fair investigation on the issue.”

Officials at Uzbekistan’s health ministry could not be immediately reached.

In October, the WHO issued a warning after cold and cough syrups made by another small Indian firm, Maiden Pharmaceuticals Ltd., were potentially linked to the deaths in Gambia. But India’s main regulator, the Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation, last month rejected the WHO’s findings and said that samples taken from Maiden’s plant didn’t find any toxic substances. The company has denied any wrongdoing.

Drugs Controller General of India V G Somani said the the global health organisation’s warning caused “irreparable damage” to the reputation of the Indian pharmaceutical industry.

Just a week later, news reports began trickling out of Uzbekistan of deaths linked to a different Indian firm.

The timing put Indian regulators in an awkward position, said Malini Aisola, the New Delhi-based co-convener of the All India Drug Action Network, an independent medical watchdog.

“These incidents have already caused a huge stir and immense pressure,” Aisola said. “It’s a huge industry and India is quite proud of the fact it supplies low-cost generic medicines not just to poor countries, but to developed economies.”

--With assistance from Nariman Gizitdinov.