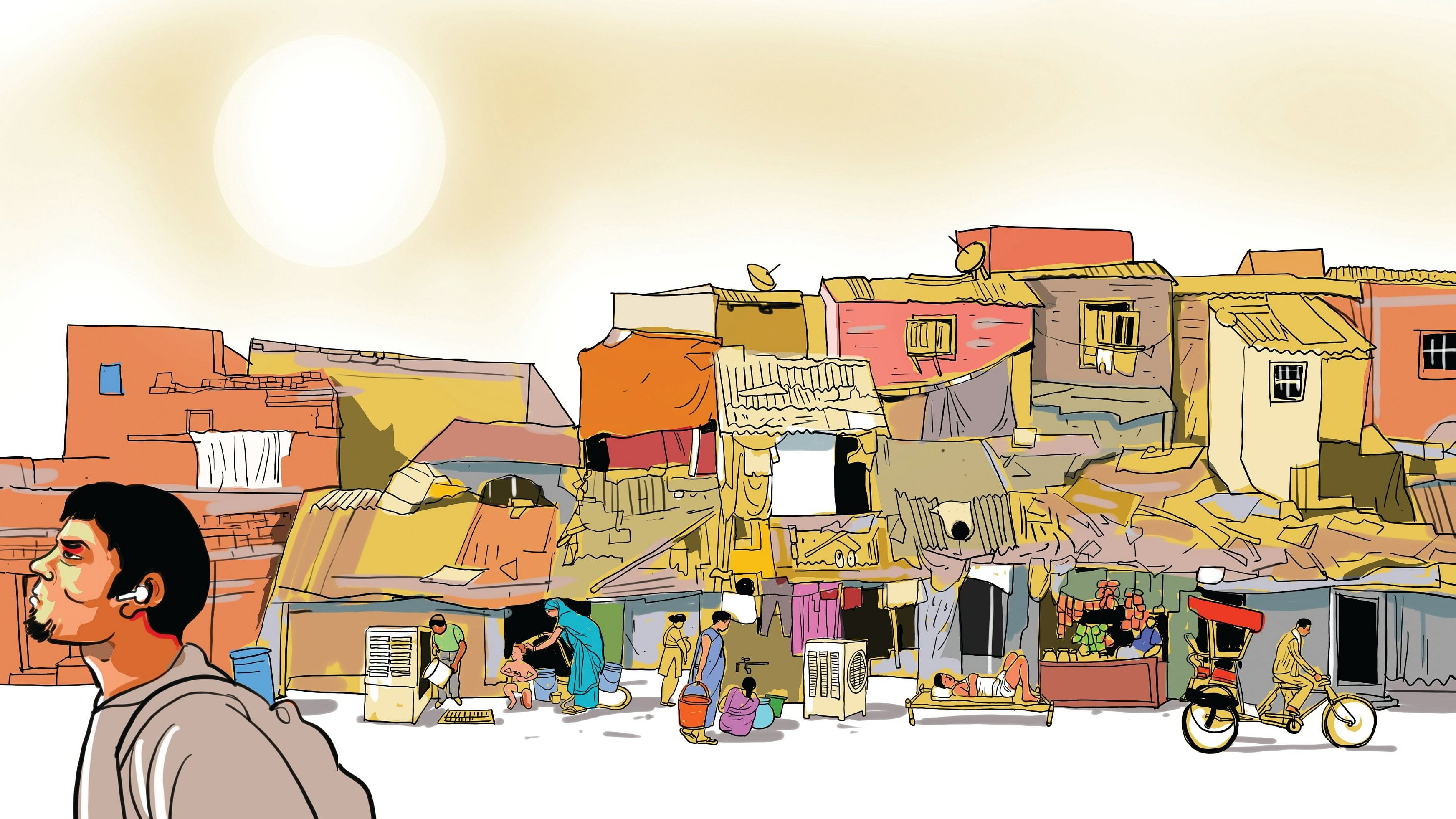

DH Illustration

Credit: Deepak Harichandan

It’s a little past noon on June 15. I hop out of an underground metro train in Delhi to get into another. My next train plies above. The air conditioning is ineffective. The train stops every few minutes, blasting a gush of hot air on our faces each time. There are 25 stops to get to my destination. I alight and hail an autorickshaw. The ride feels like somebody has a hair dryer positioned on me. To distract myself, I put on ‘Kabir Bhajans’ by Kumar Gandharva and plug in my earphones. An hour and a half later, I arrive in a low-income colony in North East Delhi’s Sundar Nagri.

Located 25 km from the Parliament, Sundar Nagri was once the handloom citadel of Delhi. Now residents are involved in selling vegetables, working in factories, making bindi, rakhi and toys and, very few, into weaving. I am reminded that Kabir Das was also a weaver.

According to the India Meteorological Department, Delhi-NCR is about a week away from monsoon and I am here to understand how the killer heatwaves affected these residents. World over, the climate crisis hits the poor disproportionately.

A conversation with my ‘cook aunty’ got me thinking about this. “Last year, a student was selling a small room cooler for Rs 800. I was not carrying so much money that day and I also forgot to borrow from you. The next day, the cooler was gone. I never came across a cooler so cheap,” she told me. She regrets not having a cooler this year. So every day, she sits a good five minutes in front of the cooler in my flat, before getting on with the kitchen work.

Her words brought into focus the inequality, the disparity between the haves and have-nots.

I come from a lower-middle-class family in Madhya Pradesh. Between my brother and I, we earn modestly. I am a freelance writer. I work remotely. I have a choice to stay indoors, steadfastly next to my cooler. That choice is a privilege, I fully know.

Buying more ice

I have a water bottle and some ORS packets in my backpack but I seem to have forgotten to pack my cap. So using my bag as a sunshield, I start walking towards the colony. Street sellers are getting ready for the Saturday market ‘Sani haat’. Some are arranging clothes, spices and utensils in neat rows on slatted platforms. Some are tying yellow and blue tarpaulin sheets overhead. Some are taking water breaks. It is 2 pm.

Close to where the market ends, I meet Bhagwati Devi. The 60-year-old sells a variety of things — fryums, cold drinks, cigarettes and pan masala. Squinting her eyes, she examines the sparse crowds passing by. Her face lights up when a woman stops by to get fryums for her kid.

Two weeks ago, she was bedridden because of heat stroke and diarrhoea. “I am old. I can’t take this heat but I have to come back to work,” she tells me in Hindi.

According to a report, the demand for ice creams, dairy beverages and curd rose over 40 per cent this summer. So Bhagwati’s cold drinks must be selling quite fast, I think out loud. She lets out a sigh and says, “People are not stepping out much. I may be selling 2-3 more cold drinks per day than last summer.”

A recent survey of 700 street vendors in Delhi by Greenpeace highlights the slump. Titled ‘Heatwave Havoc: Investigating the Impact on Street Vendors’, it found that 49.27 per cent of respondents experienced a loss of income during heatwaves, with 80.08 per cent of them acknowledging a decline in customer numbers.

Growing expenditure is Bhagwati’s bigger worry. “I am spending Rs 50-Rs 60 more daily to keep my stock cold. Lately, the ice is melting in 12 hours.” Nonetheless, she is glad to have an ice box. “I don’t have a refrigerator at home. My family keeps water bottles in the ice box and enjoys chilled water,” she shares coyly.

She moved to Delhi from Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh, four decades ago. Neither had such extreme weather back in the day, she reminisces. “Earlier, in Aligarh, we knew there would be nine very hot days and then rain would come. Now, who can predict?” she asks me. I nod, thank her for her time, and head for the colony.

I am staring at a narrow alley in front of me. Only one person can use it at a time, either on foot or cycle. In places, hutments, all ‘pakka’, are leaning or stacked on each other, like a collage out of a scrapbook.

I am looking for Meenakshi, a homemaker. A kid guides me: “Go straight and knock on the house that has two ‘charpai’ (woven bed) outside.” I set off. I turn back and see that five to six kids are following me like ants in a line.

Cooler stories

Meenakshi lives in a joint family. It’s a two-floor house, with one room on each level. Her room on the first floor is the most sought-after because it has a cooler. Meenakshi, her husband, her children and her brother-in-law’s children — eight of them — sleep in the 10x10 space. There is no legroom to sprawl but their cooler and a refrigerator they bought last year make up for the discomfort, she says.

We sit under the fan in the ground floor room, where her father-in-law lives. I ask the colony kids when they will go and play. The summer vacation is on. “Mummy doesn’t let me go outside in this heat,” says one boy, 6. His sister, 9, reveals the backstory: “Bhaiya, his nose starts bleeding. It’s so hot this time. Even my father is not going out in the afternoon to sell vegetables.” Meenakshi pitches in, “Last week, my son went to a shop to buy toffee around 5.30 pm and his nose started bleeding. Imagine! When I was growing up, we would go out to play after 4 pm or 5 pm.”

Meenakshi has been using the cooler non-stop since April, switching it off only to fill the water or when she has to cook. “I can’t keep the fan and cooler on while cooking. The room is small, so the flame on my gas burner keeps going out. I have to wake up at 5 am and finish the cooking and other chores by 8 am, before the room heats up,” she explains. She says unlike other parts of Delhi that are reeling under water shortage and power outage, their colony has no such issues. “Only one day, there was no water supply,” she adds.

Her father-in-law stays at home like her. He is struggling with sleep. On most nights, he shifts restlessly on his bed. He only has a humble, noisy ceiling fan in his room. Come morning, he opens the door with hopes of letting in cool air. All day, he moves between the ‘charpai’ outside and his bed inside trying to catch some sleep.

Our conversation returns to the cooler. My extended family lives in Parichha, a village once known for jaggery. I spent many summers there. We had a cooler, which we rarely used. Our family used to cover the roof of the house with wood and leaves (making a ‘chappar’) and that was enough. In my home in the town of Shivpuri, prepping a cooler was a family ritual. During winters, we would stow the cooler under a cover that my mother would make from her old sari. And when summer approached, we would clean it with surf and water, change the cooling pads, oil the motor, check the water tank and then install it outside the window on a stand.

Meenakshi is itching to tell a story. She says, “When my brother was born, my mama (mother’s brother) gifted us a cooler. We were living in a different slum in Delhi. We were the first family to have a cooler. Every time we installed the cooler at the start of summer, kids in the slum would come to our house to see it. Everyone wanted to be our friend.”

Fond memories give way to harsh realities as Meenakshi says, “Because of health concerns, my husband doesn’t want me to go back to making and selling bindis. But I feel I should. We are using the cooler all the time. Electricity and water bills have gone up.” Her husband makes parts for water tanks in a factory.

It’s around 3.30 pm. My shirt is clinging to my body. Beads of sweat have erupted on my forehead. The foul smell of the open drainage outside the house is making me nauseous.

Toddler cries

I meander through the alley, walking past brick-exposed homes, hoping to strike up a conversation with other residents. I see a woman making rakhis for the festival of Raksha Bandhan, coming up in August. She introduces herself as Shabnam.

Her house is cramped. It belongs to her sister. She is living here to save on the rent. However, she pays rent to use the washroom upstairs — it belongs to her neighbour. I can see a table fan and a 'matka’ (clay water pot) from the door.

“My father gave me a cooler as part of my dowry. But since I have no space for it here, I left it in Bareilly (where she shifted from last year),” Shabnam says while disentangling the rakhi threads.

“My husband and I have got used to the heat. I also wash my face and feet for respite from time to time. But I want to have a cooler for my toddler. I feel bad when he cries,” she says, her eyes welling up. She gets up and picks up her toddler. She takes him to the whirring table fan and then wipes his face with water.

She takes up seasonal jobs like making rakhis and her husband toils in a factory. Despite the dual income, rising expenses are pinching the family of four.

“Our income has not increased but my older kid keeps asking for ice cream and cold drinks. How can we deny them this summer?” she asks. She is also buying more milk. “I don’t have a fridge. It’s a struggle to prevent the milk from curdling. If a guest visits, we get a new packet. In my parent’s place, we would save the milk by placing it in the tank of our cooler,” she shares.

The survey cited earlier says household expenses of street vendors shot up by Rs 4,896.52 on average during extreme heat months. Children’s demands for soft drinks and heightened healthcare costs had increased the financial strain, half the vendors said.

The report also underscored the physical burden — 73.44 per cent experienced irritability while 66.93 per cent suffered from headaches, 67.46 per cent from dehydration, 60.82 per cent from fatigue and 57.37 per cent from muscle cramps.

Shabnam and my conversation peters out, a sign that I must move on.

‘Nothing changes for us’

On my way out of the colony, back to the ‘Sani haat’, I meet a couple — Sunita and Jagdish Pal. They are selling vegetables. Jagdish isn’t pleased with the story I am working on. “You (journalists) come, make your story, and nothing changes for us,” he says. I get his cynicism.

The Delhi Disaster Management Authority drafted a Heat Action Plan last year but it is not yet notified. For vulnerable populations, it calls for setting up shaded areas and water points, providing ORS packets, organising medical camps, and shifting schedules for outdoor workers.

Over a call later, Greenpeace India’s senior campaigner Avinash Chanchal tells me that street vendors spend 16.2 years of their lives as street vendors on average. Yet, not many were consulted for the heat action plan. Emphasising that extreme heat widens the socio-economic gap, he says, “Money that could be spent on recreational activities for their kids is being spent on things needed for survival.”

It’s past 4.30 pm. Walking towards the metro, I am gripped with thoughts. What was the summer of 2024 like for me, especially since May when the mercury has stayed above 40°C consistently? I skipped my evening runs or walks. I cut down weekend visits to plays or comedy gigs. I hung out in places that had air conditioning. A mid-day outing to a second-hand book bazaar left me with a high fever. I stocked my fridge to capacity because I did not want to run to the grocery store for last-minute milk, mangoes or ‘dhaniya’. I am more irritable and less productive because I am struggling to fall asleep — 4 am is the new 11 pm for me.

Before hopping back on the metro, I stop by a sugarcane juice stall at the end of the ‘haat’. An old man is sitting in front of a cooler, enjoying his little oasis. Sipping my juice, I tell him, “Too much heat.” He replies with a smile, “Barish se aur haalat kharab hogi, umas badh jayegi (Rain will make it worse; humidity will increase).”

His comment takes me back to what Bhagwati had told me about “the fate” of vulnerable populations. She said, “Not just the summer, the weather in Delhi is becoming extreme year after year. Wait for July. The monsoon will hit and these ‘naalis’ (drains) will start overflowing with sewage, stinking up the place. You won’t be able to stand here. Winters are becoming harsh too. Who can control nature? You have to learn to live with it.”

Like this story? Email: dhonsat@deccanherald.co.in