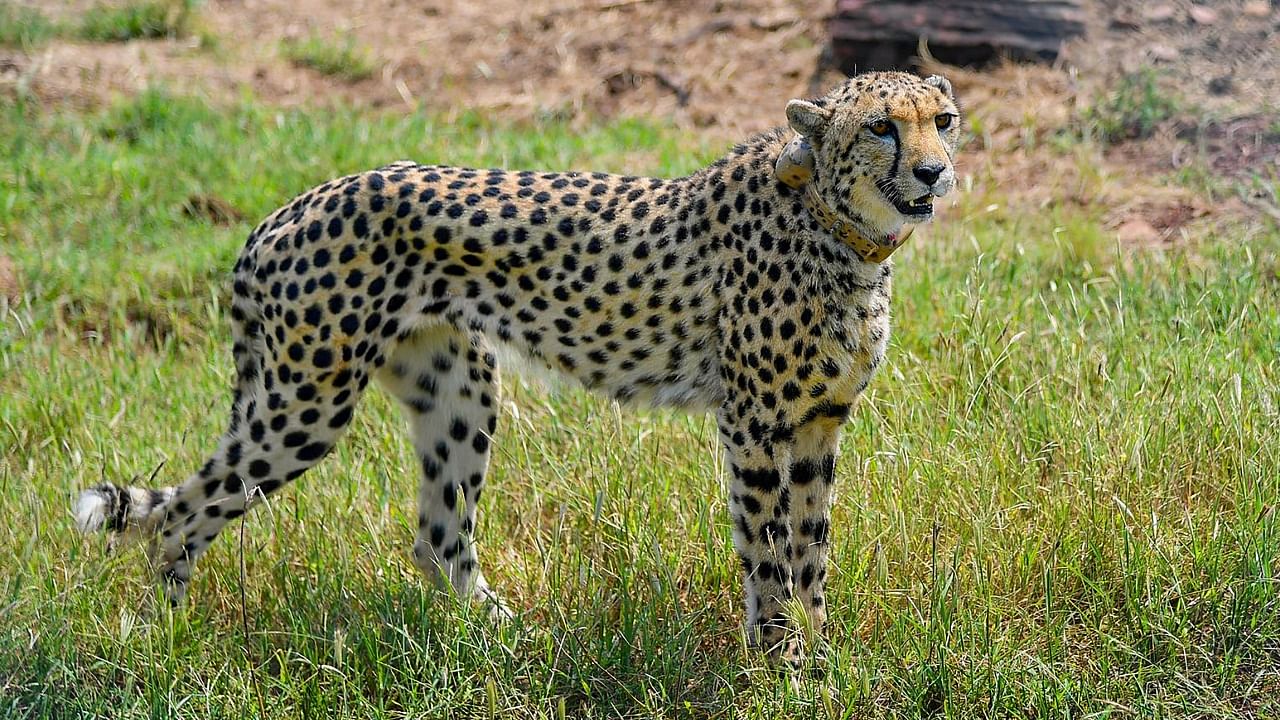

Prime Minister Narendra Modi cranked a lever and let three cheetahs out in Madhya Pradesh’s Kuno National Park on September 17, as part of a historic translocation of the big cats from Namibia to India. The cheetah walked on Indian soil again seven decades after it was declared extinct.

The project, which has received praise and skepticism from conservationists, is already embroiled in political controversy, with a fight for credit between the ruling BJP and Congress. The latter claims that the project was started in 2009 when the grand old party was in power.

The cheetah species dates back about 8.5 million years, and the animals were once found in great numbers across Africa, Arabia and Asia. They now live exclusively in Africa, other than a tiny population in Iran. Their population is estimated to be fewer than 8,000, down by half over the past four decades.

As the credit war goes on and the viability of the project itself is debated, let us take a look and see why the animal went extinct in India in the first place:

Hunting, poaching, diminishing prey base

Cheetahs were previously found in various parts of India, mainly in Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh. Maharaja Ramanuj Pratap Singh Deo of Koriya princely state hunted down what are believed to be the last three remaining Asiatic cheetahs in India in 1947. The species was declared extinct in 1952.

Hunting and poaching are the most important factors in the cheetah’s extinction. However, a diminishing prey base in the region it prowled and the decimation of the grasslands habitat also contributed in a major way.

Loss of habitat

In India, cheetahs found home in scrubs, grasslands, arid and semi-arid open lands. In 1952, India was a young republic, majorly dependent on agriculture for many decades leading up to independence and even after. This led to acquiring grasslands and converting them into agricultural land. This chipped away little by little on the spotted cat’s habitat, until one day, it disappeared altogether.

Domestication

The habitat and prey of the cheetah still survived till much later. Tracing the issue further back to the 12th century through the Mughal empire, the big cat was reportedly being taken out of the wild at an alarming rate to be domesticated for sport or hunting smaller animals and kept in captivity. Akbar is said to have taken out nearly thousands of cheetahs during his near five-decade-long reign for his royal showcase.

The reason this was so easily achievable was that unlike other cats like tigers and leopards, cheetahs are not fierce. They are downright docile creatures from the cat family that can be domesticated like a house pet within six months of acquiring.

When the British started building their empire in India, cheetahs were already scarce.

Genes

The animal has faced extinction before, when its population fell sharply, leading to inbreeding, which means mating with relatives. This shrunk the gene pool of the animal, decreasing the genetic variations in the population. This made it increasingly difficult for cheetah cubs to adapt to their environment. Even today’s cheetah populations have low genetic variability. They are also vulnerable to infections from domestic cats.

It remains to be seen how the new members of the Kuno biodiversity adjust to other cats, smaller animals, human habitation, and the environment.

Fourteen other nations, including Jordan, Morocco, Syria, Oman and Tunisia have seen cheetahs go extinct in the past 70 years.