When you travel along the west coast of India, a 2,050 km-long chain of Indo-Aryan language zone beginning with Sindh in Pakistan, imperceptibly gives way to the family of Dravidian languages starting from Karnataka.

Karwar taluk in Uttara Kannada district marks this site of linguistic transition, where Marathi and Konkani slowly give way to Konkani and Kannada.

Konkani is the lingua franca of Karwar. However, Kannada is used for practical purposes, like in most other minority language speaking parts of Karnataka.

The proportion of Konkani speakers decreased after the linguistic reorganisation of the states in 1956. Census records show that 65% of residents in Karwar taluk recorded Konkani as their mother tongue in 1951; the latest census reports put the number at 53%.

Konkani continues to be spoken along the Konkan coast all the way south to Kasaragod in Kerala, but only as a significant minority language.

Karwar taluk, as well as the rest of Uttara Kannada, is unique in that Konkani is also spoken by the ethnic groups of African descent — the Siddis. The Siddis of Uttara Kannada form three major groups based on religion: the Hindus, Catholics and Muslims. The Hindu and Catholic Siddis speak their own dialect of Konkani as mother tongue.

A wide array of castes in the region too speak Konkani, including many artisanal communities that are not as numerous in Dakshina Kannada’s Konkani speaking communities. Konkani is such a mainstay of local society that in records of the colonial British government, non-Konkani speakers, including Kannada speakers, are shown to have known Konkani as a second language or to have profusely used Konkani words in their own language.

Distinct identity

The Konkani spoken in Karwar is distinct from the varieties spoken in Goa, as well as further south in Udupi, Dakshina Kannada, and Kasaragod districts. Uttara Kannada Konkani is also called baḍgī in Mangaluru Konkani, which literally means “northern”.

The dialect here is influenced more by Marathi than the Konkani spoken in Mangaluru but also has a significantly greater influence of Kannada than in Goa.

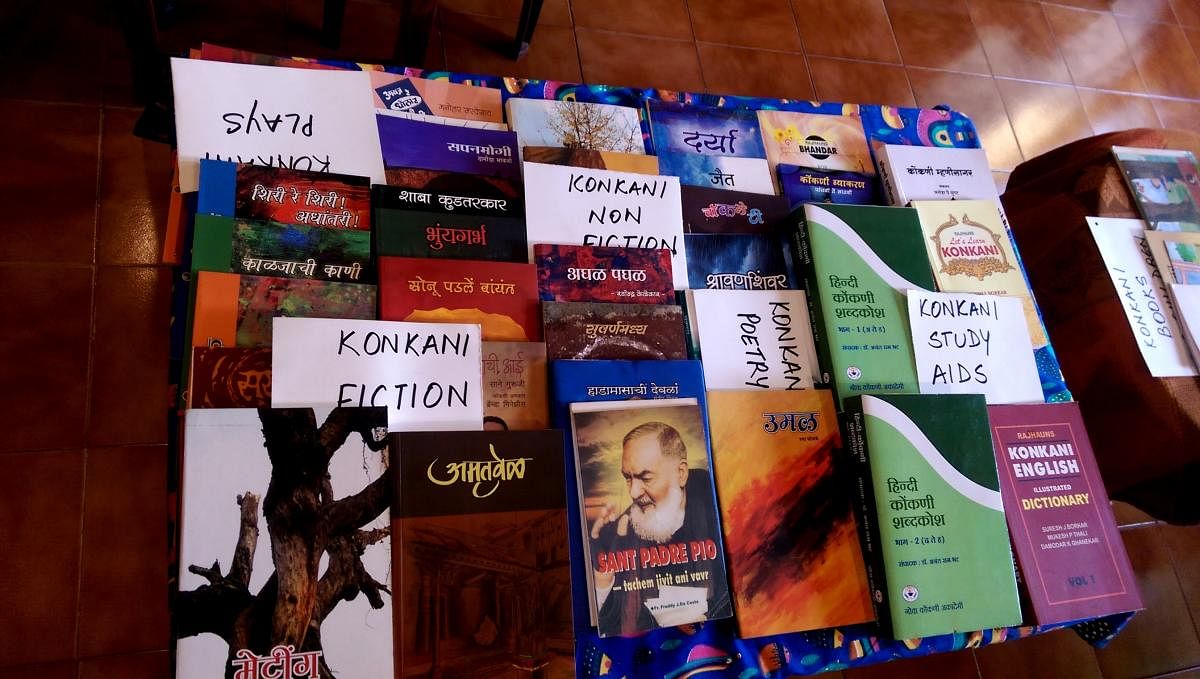

As one of a handful of Konkani majority towns in British India, Karwar served as a base for Konkani activists, playing an important role in the 20th century Konkani language agitation; as a non-literary language, Konkani needed to be actively promoted and cultivated for written purposes by the community. In 1939, the first ever Konkani Parishad was held in the town, led by prominent advocate Madhav Manjunath Shanbhag.

Interestingly, among the resolutions of the session was the decision to adopt Devanagari as the script for Konkani, a development that reflected a desire to maintain a distinct linguistic identity.

Devanagari script

Many locals were familiar with the Devanagari script, which was used in Marathi — a language many used for official purposes. In British Bombay, migrants from Karwar — both part of Bombay Presidency at the time — joined their Goan and Mangalorean counterparts in contributing to the growth of Konkani literature.

In 1935, Onvllam, a collection of Konkani short stories written in Devanagari by writers from Karwar and Mangaluru in their respective dialects, was published in the metropolis.

Mahabaleshwar Sail, a Saraswati Samman winning author who wrote both in Konkani and Marathi, was born and raised in Majali, a fishing village right across the Kali river, in Karwar.

Although Sail began his career in Marathi, he eventually switched to writing in his mother tongue. Sail’s first Konkani novel, Kali Ganga (1996), was set in rural Karwar. Its title references the Kali river, which flows across the town. His 2016 novel, Hawthan, is about Karwar’s kumbar (potter) community and their traditional craft.

According to Konkani scholar Olivinho Gomes, Sail’s book Poltoddchem Tarum (A Ship from the other Bank of the River) is “symbolical of the river Kali that separates Goa, the original abode of the Konkani speakers, from Karwar.”

Today, Karwar is no longer a major centre for Konkani activism and has largely been taken over by Mangaluru, and Panaji in Goa. However, as a linguistic zone between Konkani and Kannada as well as Indo-Aryan and Dravidian languages, Karwar’s history and culture are important in helping us understand how multilingualism and minority language spaces exist and assert themselves within a socio-political context.