For decades, the border city of Belagavi is more known for linguistic tensions. Veiled under this dispute, is a lesser-Googled architectural heritage, which reflects a fine blend of Kannada and Marathi cultures. A walk through the webbed lanes and bylanes of the swiftly transforming city offers a glimpse of not just big shopping complexes, malls and heritage gems like the fort and temples, but also simple and beautifully designed houses.

These houses, which are treasure troves of beautiful architecture, are a witness to our glorious past and help us trace the structure legacy of the ‘second capital’ of the state. The different styles of houses that Belagavi has seen over the years can be categorised into three, the first phase starts with the early 18th century.

Indigenous concept

During that period, the elements of Indian aesthetics were invested in the houses. The houses were built in compliance with eco-friendly materials that were locally available. They were predominantly linear-shaped structures. The rooms were one behind the other, offering a train bogie-like appearance. Also, most of the houses had a small secluded room with absolutely no light entering it, they were meant for nursing mothers. The houses shared their walls with the neighbouring houses, and the concept of a compound wall was absent. Each house directly opened to the lane and each narrow lane called a galli had 20 to 30 such houses. Such narrow roads and houses made of indigenous organic materials typically had an influence of the medieval period.

The common walls and the sloped roofs with hand-moulded country tiles (similar to terracotta tiles) protected the houses from harsh monsoon and scorching heat. Black basalt stone, laterite soil, sun-dried mud bricks and cob (balls of subsoil, water and straw) were mainly used in the construction. Stone construction formed the foundation which extended to around six to seven feet in depth and then wooden truss was used for the roof structure.

“Due to smaller windows and the narrow capillary-like allays (Galli), there was less scope for light to enter the houses and so, most of the houses either had a front yard, backyard or courtyard which provided ventilation and served as a commonplace of activity as well. Open dug wells were the main source of water supply to the families,” explains Suyash Khanolkar, a young architect, who is documenting these houses along with like-minded people.

He adds that these houses were designed so skillfully that they could

withstand even extreme climatic conditions. The houses also imparted a culture of relaxation and marked a sense of

orderliness. Ultimately, they celebrated cultural richness.

Such houses emerged mainly during the period of the Adilshahis of Bijapur and then under the Maratha Patwardhans of Sangli. Today, such houses can be seen in areas like Shahapur and Vadgoan, which were small villages back then.

“During the Adil Shahi period, Shahapur was called as Shahapeth. These heritage streets and lanes were formed occupation-wise. So, there were lanes occupied by jewellery makers, accountants, priests, etc. Even today, the lanes of these areas retain the names such as ‘Saraf Galli’ (street of jewellers), Achar Galli (street of priests) and Kacheri Galli (street of offices). Even the temples of these areas are architecturally similar,” elaborates historian Smita Surebankar.

Professor Nishita Tadkodkar, an architecture expert, said that in such houses, the front room which opened to the lanes were generally used by men for carrying out their trades and the kitchens and back courtyards were used by women. This concept is visible in the houses of weavers in Khasbag area of the city hitherto. There, weavers have their looms and smaller shops in the front rooms followed by other rooms used by the family.

Colonial bequest

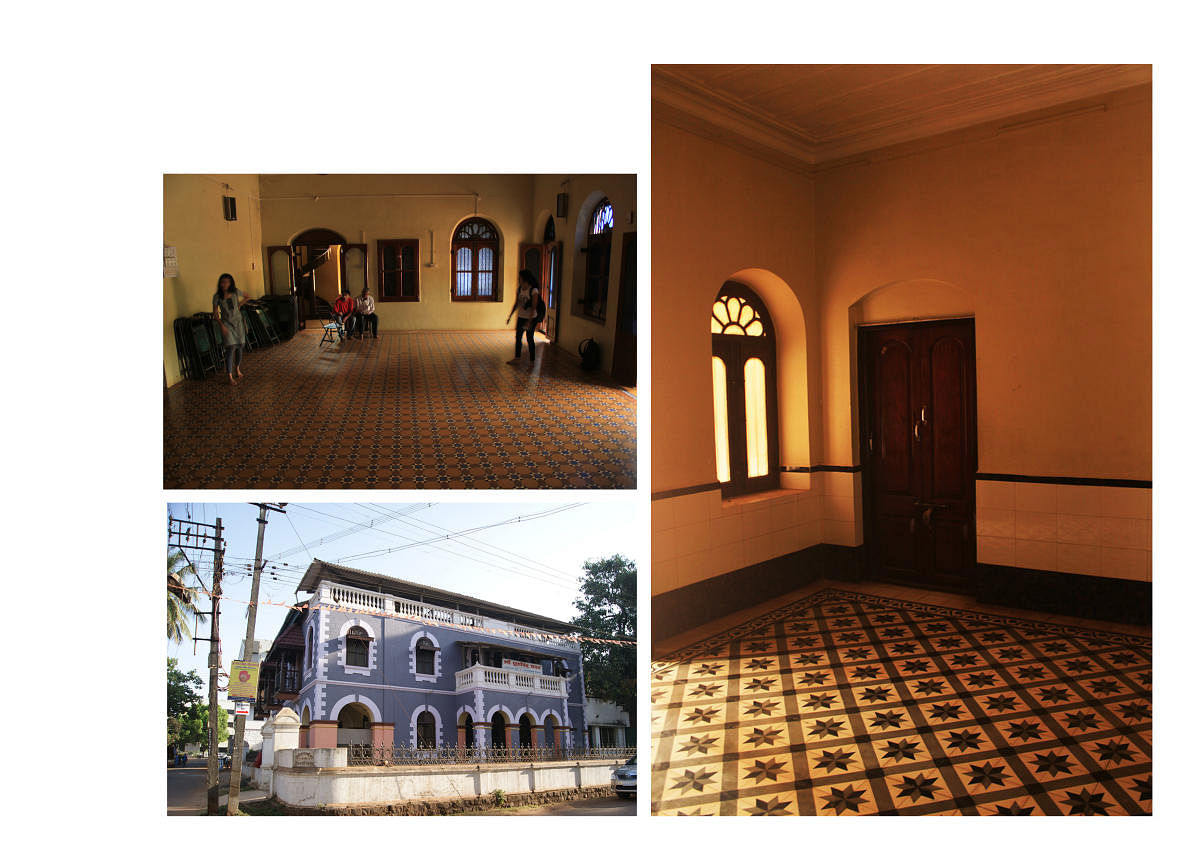

In 1900s, another type of houses emerged in the present-day areas like the Gondhalli Galli and Risaldar Galli. These houses had a colonial influence in their designs and materials used. These houses were made of stones while vibrantly stained glasses and cast iron railings (grills) were extensively used to beautify them. The design mainly had arches and bigger openings unlike the former which was typically linear in style.

Many were two-storey buildings. “During the mid-1800s and 1900s, Belagavi grew into a semi-urban area influenced by cities like Pune. This was a transition period and the place was becoming politically significant. Many lawyers and intellectuals, though being nationalists, bequeathed English architectural style,” said Ravindra Gundu Rao, a conservation architect from Mysuru.

He said that these houses were a blend of Indian and British styles. While the exteriors of the houses, especially the front portion, had sophisticated

British elements like the Mangalore

pattern tiles, laterite soil (which was sourced from the coast), ashlars and European style windows, the interiors remained more Indian with courtyards and the ‘Tulsi Katte’. The ‘Bhate’s house’ (now called Swami Vivekananda Memorial), which hosted Swami Vivekananda and Bal Gangadhar Tilak, is a typical example of such a house. Such houses can be seen in areas of old Belagavi city and Tilakwadi now.

Barrack bungalows

The third type of houses came up in the cantonment area (military station) during the 1900s. These houses were mainly constructed for the British officers and their servants. These houses with a utilitarian mindset with huge compounds, trees with dark foliage and bigger rooms for special purposes and activities greatly suited the lifestyle of the British officers. They were quaint, laterite bungalows with servant quarters in the premises.

“Concepts like cross-ventilation, light peeping into the building and rooms were the highlights of such British bungalows. The roads were wide to accommodate vehicles and the area adapted more to a colonial style of urban planning. The architecture of these bungalows was similar to the British bungalows seen in other parts of the country. Unlike the contemporary Indian buildings, these buildings had better ventilation and interiors. They had separate rooms divided by walls,” Ravindra said.

Though many of these houses have

undergone minor structural changes

suiting the modern day needs and are marked by age, they lend a character and flavour and a sense of nostalgia to the city even to this day.