The roots of Dasara can be traced back to the time of the puranas, which stress the worship of Goddess Durga, revered in Karnataka as Chamundi, Banashankari, Durga, Vaishnavi, Varahi et al.

Archaeological inscriptions help reconstruct the history of Dasara traditions. Writings of several foreign travellers who witnessed the festival offer vivid details.

The festival finds its first presence during the time of the Kadambas, who ruled from Banavasi (in present-day Uttara Kannada).

During the rule of the Chalukyas of Badami, the festival worshipped mother goddess or devi. It was more religious and ritualistic than celebratory in nature. In other words, it was strictly observed as prescribed by the puranas and Vedic texts.

Under Vijayanagar Empire

The tradition continued, particularly during the rule of the mighty Vijayanagar Empire. The dynasty, established in 1336 AD, continued to remain in power by encompassing swathes of geopolitical regions in south India till its collapse during the Battle of Talikota in 1565 AD. The kings of Vijayanagar shaped the worship of Mahishamardini.

Travellers and traders from different lands visited the empire. Niccolò de’ Conti, an Italian traveller from Venice, visited Vijayanagar around 1420 and wrote about Mahanavami. Devaraya II was the king then. Abd-al-Razzaq, a traveller from Persia, described the pomp and gaiety of Dasara.

Fernao Nuniz, a traveller from Portugal who visited Vijayanagar during the reign of Achyuta Raya described a ritual of the king’s review of the troops thus, in the book Hampi: Discover the Splendour of Vijayanagar: “At the end he takes a bow in his hand and shoots three arrows, namely one for the Ydallcao (Sultan Adil Shah of Bijapur) and another for The King of Cotamuloco (Sultan of Golconda) and yet another for the Portuguese.”

Fernao also described wrestling and wrestlers who participated in competitions held during the occasion.

During the reign of Krishnadevaraya (1509-1529), the might of the rule spread across South India and Dasara became an important festival.

Traditions were revamped. The Portuguese traveller Domingo Paez’s visit to Vijayanagar coincided with the heydays of Krishnadevaraya, who by the time had renovated the Mahanavami Dibba — a platform from where the royalty watched the army march-past, war games and royal procession during Dasara — commemorate his victory against the gajapatis (rulers of Odisha). It was also called the victory house. In the said book, Paez also described how he was swayed by the festival: “I have no words to express what I saw... with my head so often turned from one side to another that I was almost falling backwards off my horse with my senses lost.”

Ways of the Wadiyars

The royal dynasty of the Wadiyars, which came to power around 1399 AD, had under its control limited geographical territory. Earlier, they were the vassals of Vijayanagar rulers. With the decline of the political power and prestige of Vijayanagar after the Battle of Talikota, the Wadiyars strengthened their base by expanding their hold.

By extension, Dasara became a celebration to behold.

Raja Wadiyar, who ruled during the first quarter of the 17th century, is said to have revived it. In 1610, it was celebrated at Srirangapatna to showcase his might against his earlier vassal chiefs of Vijayanagar. He codified the system of celebration.

The Dasara celebrated for the first time at Srirangapatna was more culturally rich than that was celebrated at Vijayanagar.

It’s this Dasara we celebrate today.

During the time of Chikka Devaraja Wadiyar, Dasara was a spectacle. Mysore State became a military state and also held some political clout. He was the contemporary of Aurangzeb, the Mughal emperor, and ruled between 1645 and 1704.

Some texts also refer to the procession of the army in the capital on the penultimate day of Dasara.

He tried to diversify Dasara by taking it to rural areas.

The reign of Krishnaraja Wadiyar II (1734-1766) upheld the beauty of Dasara. Works like Noorondayyana Soundarya Kavya and Maharajara Vamsavali deal with the celebrations, rituals, gathering, traditions and customs at Srirangapatna.

The one celebrated in 1740 has been explained lucidly. Chieftains, ruling dynasties, neighbouring states were invited to participate in Dasara.

Monks and pontiff heads of several monasteries and the heads of Vaishnava, Srivaishnava and Shaiva sects were present. There’s a lengthy description on wrestlers and their fighting skills.

The celebration concluded with the royal procession, the king seated on the howdah, followed by his army that consisted of foot soldiers, horses and camels.

During the period of interregnum —when Hyder Ali and later, his son Tipu had usurped the throne — the members of the Wadiyar dynasty celebrated Dasara, and it was confined to their royal household. It was a low-key affair. After the death of Tipu Sultan in the IV Anglo-Mysore War in 1799, the capital was shifted to Mysuru.

Later, it became the royal capital from where Dasara came to be celebrated during the time of Krishnaraja Wadiyar III.

Purniah, the dewan of this young prince, is said to have taken more initiatives to hold Dasara in consultation with the officials of the English East India Company. It was from 1805 onwards we have records regarding the revival of Dasara from a new place, on par with what was held earlier at Srirangapatna. It entered a new phase with well-defined rituals and customs.

People’s festival

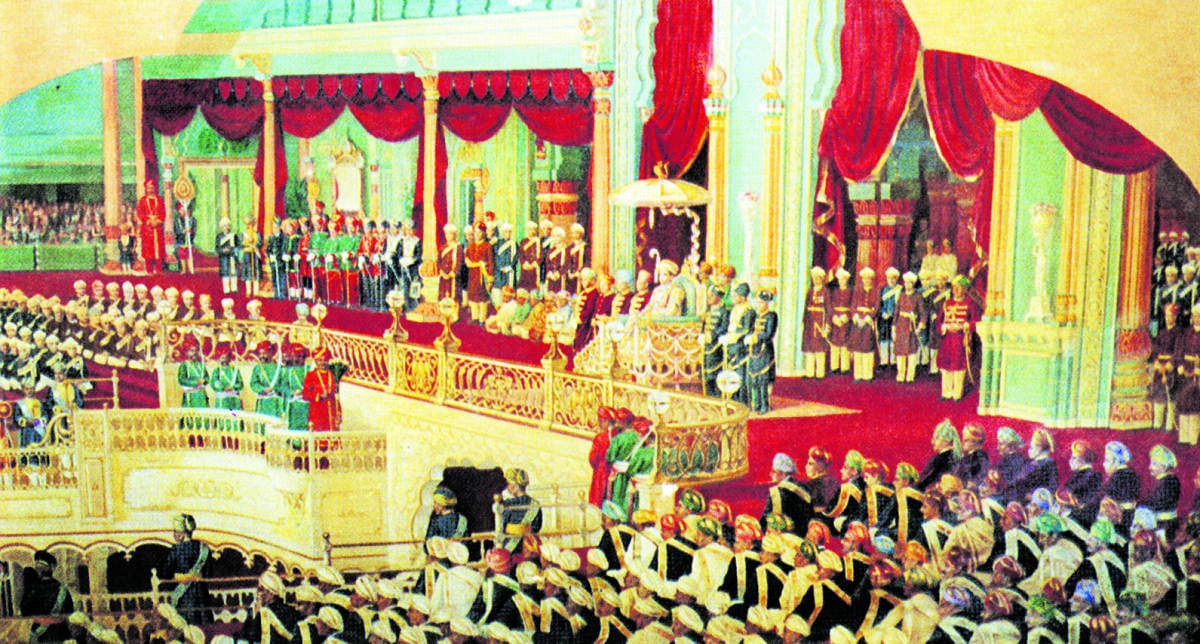

In 1805, it began as a public function, and the wooden palace that existed earlier was the centre of attraction. With the involvement of non-officials in Dasara and rituals, it was diversified.

When the princely state of Mysore was brought under the control of Commissioners rule (1831-1881), its celebration was confined to the palace and rituals were conducted as usual.

After the transfer of administration in 1881, Dasara was revived. It was Europeanised, too, in which the king conducted special durbars for Europeans.