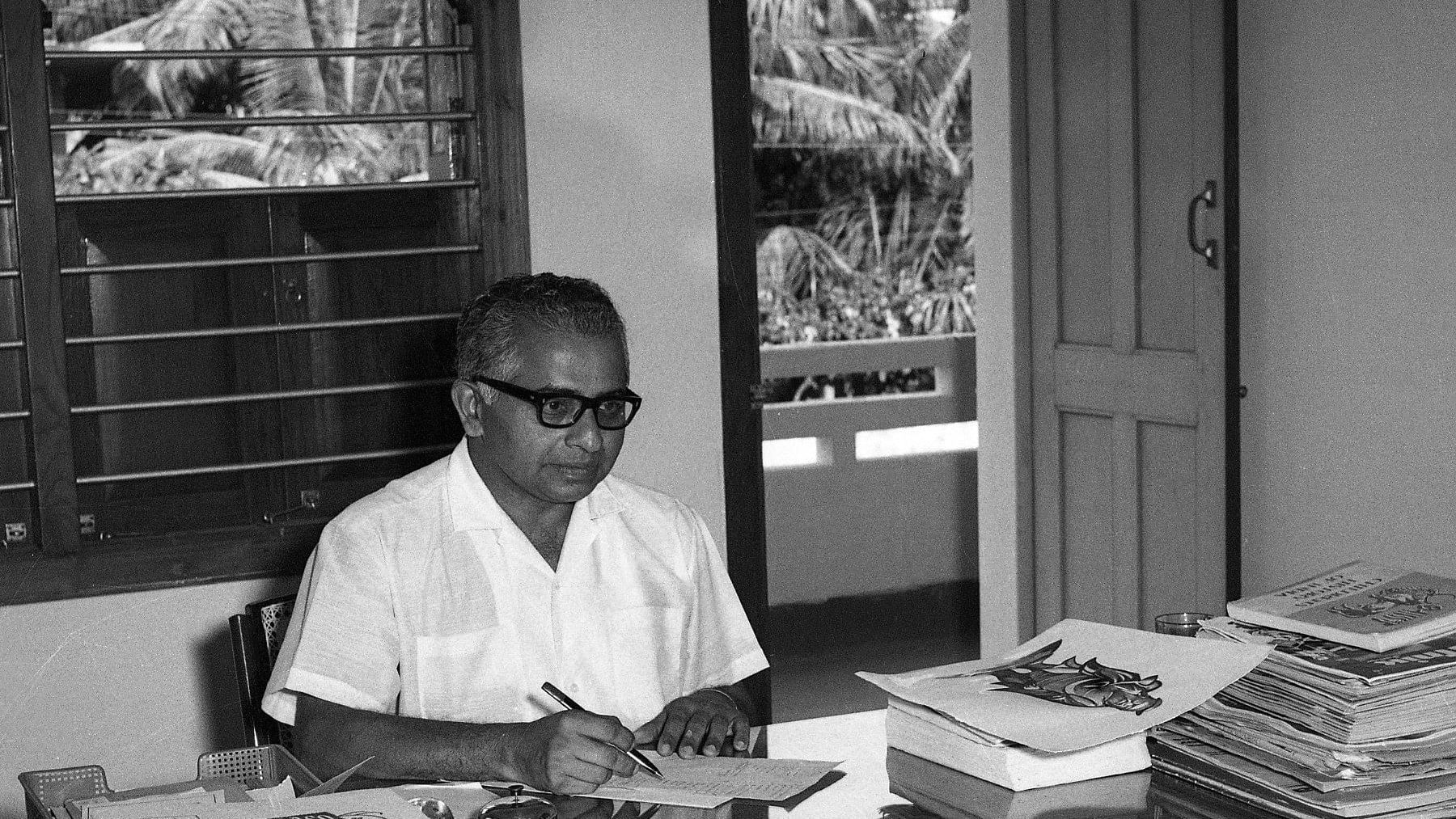

K S Niranjana _ Editor in Chief _ Jnanagangotri Encyclopedia at his chamber in Bangalore.

Credit: Special Arrangement.

Niranjana is one of the most significant writers associated with the Pragathisheela (progressive) literary movement in Kannada literature of the 1940s and 50s. The All India Progressive Writers Association, established formally at a meeting of writers in a Chinese restaurant in London in 1934, was a forum of writers who rebelled against the established literary tradition and several inequalities of Indian society based on caste and class. They rose to prominence in Hindi, Urdu and other Indian bhasha traditions.

Mulk Raj Anand, Premchand, Sajjad Zaheer, Ismat Chugtai, Faiz Ahmed Faiz were some of the eminent, original writers whose writings have relevance beyond the ideological frameworks of the Progressive Movement. The impact of the movement was pervasive and powerful, and has continued to influence socially engaged literature at different periods in many literary traditions. Some well-known writers, including Sriranga the playwright, attended the conference of progressive writers in Mumbai in 1943 and the movement began to gather momentum.

Though TaRaSu (T R Subba Rao) and ANaKri (A N Krishna Rao) were the most popular and visible writers of the movement, it is Niranjana and Basavaraj Kattimani whose fictional writings have received both popular and critical attention.

Niranjana, a prodigy, began writing in his school days. He also maintained a close alliance with the communist party and movement in later years. He was a prolific writer who wrote over 60 works, edited and compiled 25 volumes of short stories from various countries and languages in a Kannada translation. He also edited an encyclopaedia in Kannada.

Moving narratives

His short story, Koneya Giraki (the last client) is a powerful narrative about a woman forced into sex work who now, in the last moments of her life, is destitute, ill and abandoned. The last client is depicted as a vulture hovering to devour her flesh. The short story is a classic among many written by progressive writers.

Niranjana’s timeless classic is Chirasmarane (translated by Tejaswini Niranjana into English as ‘The stars shine brightly’). It is a moving narrative about the struggle of peasants in a nondescript village, Kayyuru, in the Kasaragod region. Their struggle is against a self-centered feudal system which pushes them into debt, poverty, and bonded labour. As the novel progresses, it unravels the collusion between the feudal lords, the imperial British regime, and its instruments of power, namely bureaucracy and judiciary.

The schoolmaster educates two youth, Chirukanda and Appu, about the ruthlessness of the system which meets their resistance with inhuman violence. Gradually, the community developed an awareness of the legitimacy of protest with interventions made by the communist activists. But the protest rally in the village leads to the accidental death of a policeman leading to the arrest, trial and sentencing to death of four of the village youth. The martyrdom is narrated by the author-narrator.

The power of the narrative flow, the portrayal of several characters with compassion and understanding, depiction of a rural community gradually drawn into a confrontation with imperial power — these elements make the novel’s texture complex. What is remarkable is the fortitude of the youth facing death and the emotional support that their families offer them. It is a unique political novel which depicts the inexorable but violent imperial political system without verbal rhetoric and overtly ideological interventions by the author-narrator. Long before the advent of subaltern studies, Niranjana’s novel provides a peasant-centric subaltern eye view of the collusion of feudalism with imperialism.

Historical novels

Another towering achievement of the writer is the novel Mrutyunjaya. It was translated into English as ‘Coming forth by day’ by Tejaswini Niranjana, and won the Sahitya Akademi Award for translation. It is a narrative reconstruction of the rebellion in ancient Egypt ‘4,500 years ago’, as the opening informs us. A huge, densely documented novel, astonishing in its minute details of everyday life, it is a historical novel which eschews the popular historical novel form practised in Kannada by Galaganatha and TaRaSu.

There is none of the romantic valorisation of the past, of heroism and of ‘Kshatra’ values. The canvas is of the ordinary people of the great ‘mythologised’ Egyptian civilisation. Instead, there are the entrenched systems of power, of institutional religion and priesthood. There is also the royal regime of pharaoh and regional feudal systems. These are oppressive and exploitative. In a way, the depiction of the struggle and the tragedy is an instantiation of the eternal class conflict in different contexts and conjunctures.

What the two novels share is how history can be construed as a repetition of this struggle. The novels, both ending in tragedy, are also affirmative of the spirit of rebellion and the collective power of ordinary men and women to challenge structures of power which appear to be invincible.

‘Kalyanaswami’ is another historical novel based on the legends, popular memories and his own research on Kalyanaswami of Kodagu, who led a rebellion against the British regime two decades before the 1857 war of independence. Niranjana wrote a short essay on ‘History and Creative Writing’ in place of a foreword to this novel. It is an important theorisation on the reconstruction of history in creative writing.

He argues that ‘history is not a tale about kings and queens or merely the rise and fall of empires’. History ought to be about the dynamics of change in human communities, the spirit of the age and the forms of power which shape society.

Kalyanaswamy has been described as a rioter and imposter in pro-British sources. Niranjana depicts him as a rebel against imperialism by drawing on the popular legends and the notes made by the great poet and researcher Govind Pai. He also uses a Yakshagana script, which the British administrators tried to destroy because it valorised Kalayanaswamy as a people’s hero.

In a literary career of five decades, Niranjana wrote plays, and short stories and was a full-time journalist, an influential columnist and activist. He deserves re-reading and critical attention at a time when we are celebrating his birth centenary year.