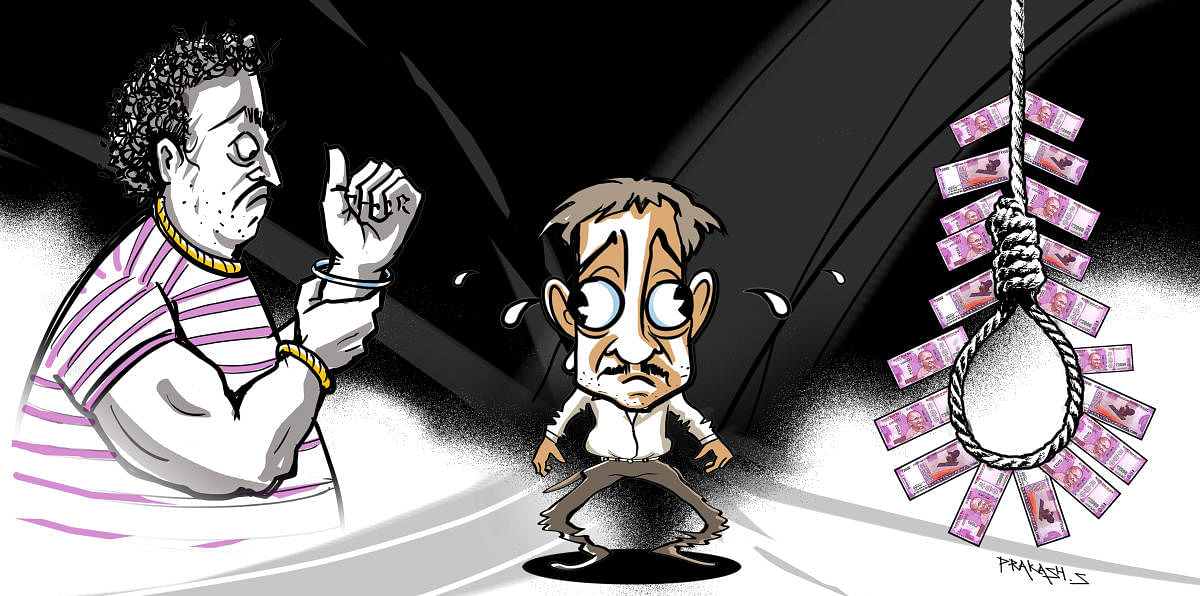

Unable to withstand harassment from moneylenders, a man got into a suspected suicide pact and killed his 12-year-old son. His 17-year-old daughter tried to stop him, but he wouldn’t listen. She ended up capturing the tragic action on a phone. Her mother hanged herself.

The two deaths, and the accompanying tragedy, occurred in the night on June 3.

Senior police officers attached to the City Crime Branch (CCB) say many families become victims of usury.

People in distress borrow money in the informal sector, especially when they have to spend on medicines and hospitals. They also get into debt when they have weddings and big ritual feasts in the family.

S Girish DCP (Crime), Bengaluru, says quite a few also borrow to invest in property, and then realise it does not bring easy returns.

“People find it easier to borrow from moneylenders because the procedure is less complicated than at a bank. Moneylenders start adding cumulative interest after two or three months and mount pressure on borrowers,” he says.

Typically, Marwadis who run multiple businesses start lending money at high interest, says Girish. The business thrives in southern Bengaluru and in old areas like Chickpet and Avenue Road. “These are the areas where we have booked the most cases,” he says.

Debt and grief: Families that gave up

* A 12-year-old brother was hanged from a ceiling fan by their father in Bengaluru. This was shot on video by the 17-year-old daughter who tried to dissuade her father. The mother hanged herself first in what appears to be a suicide pact. The couple ran into a huge debt after a chit-fund business they floated failed. They felt they were being harassed by neighbours who constantly kept asking the couple to return the money. (June 3, 2019)

* A family of four members allegedly committed suicide by hanging themselves in their house in Bommanahalli end of last year. They entered into a suicide pact as they ran into heavy debt after borrowing multiple loans from banks and moneylenders to construct a house. They took the extreme step after they realised that the amount could not be repaid.

* Husband and wife, both doctors, along with their two sons, committed suicide in Dasarahalli limits early this year because they were neck-deep in debt. It is said the family had a debt of Rs 50 lakh which they had borrowed from multiple sources, including moneylenders.

The economics of tragedy

Aspiration can lead to reckless borrowing, says economist Narendar Pani

Narendar Pani, professor and dean at National Institute of Advanced Studies (NIAS) says an increase in informal borrowing is a result of a larger economic crisis. “In an economic crisis, people come under immense pressure and borrow from whoever is willing to lend to them. Banks will not give you money unless you have collateral,” he says. That’s when people go to family and friends. “If you need more, moneylenders give it to you, but at high interest because they don’t take any security. That’s the nature of the system and the nature of the crisis,” the economist explains. He believes trying to keep up with the neighbours often drives the middle class to moneylenders. “We have a very aspirational society where you are supposed to do better than everybody else. Once you reach 35 years, it becomes a matter of which school you send your children to, and what lifestyle you adopt,” he says. In a slowing down economy, if you want to retain your status, you end up borrowing. The solution, he observes, is to scale down on lifestyle, but that is largely an individual choice. Institutions like the Institute for Social and Economic Change (ISEC) constantly study changing social structures and economic patterns. Dr Channamma Kambara, assistant professor at ISEC, has extensively researched informal moneylending. She says the lower class and the lower middle class depend on the sector almost every day. “Moneylenders, unlike banks, don’t insist on collaterals or ask borrowers to sign documents. People are all right with the high interest because they don’t have to produce documents,” she adds. Moneylenders inflate the money owed to them and use harsh and extreme measures to get the money. Their methods include verbal and physical abuse and open humiliation of the borrower in public.

Help for victims

According to the law, moneylenders must have a licence and charge interest rates as indicated in the Karnataka Moneylenders Act of 1961, advocate S Shetkar says.

“If the borrower has proper documentation, he can file a case and recover excess money collected, but nobody goes through it because it is a lengthy process,” he told Metrolife.

Meter baddi

- Informal moneylenders typically charge 15 per cent a month, which is 180 per cent a year.

- The highest interest rate for a bank personal loan is about 16 percent.

- When a borrower defaults, moneylenders add penal interest due to principal, and resulting amount is hugely inflated.

- High rates of interest are referred to in Bengaluru as ‘meter baddi.’ The term comes from meter (or something that keeps rising rapidly) and baddi, the Kannada word for interest.

Small numbers

In 2018, police filed 84 cases in Bengaluru under the Karnataka Prohibition of Charging Exorbitant Interest Act. This year, till May, they have booked 12 cases.

This is illegal

- Charging exorbitant interest (more than what is stipulated in the Karnataka Moneylenders Act of 1961).

- Threatening and inflicting violence on borrowers.