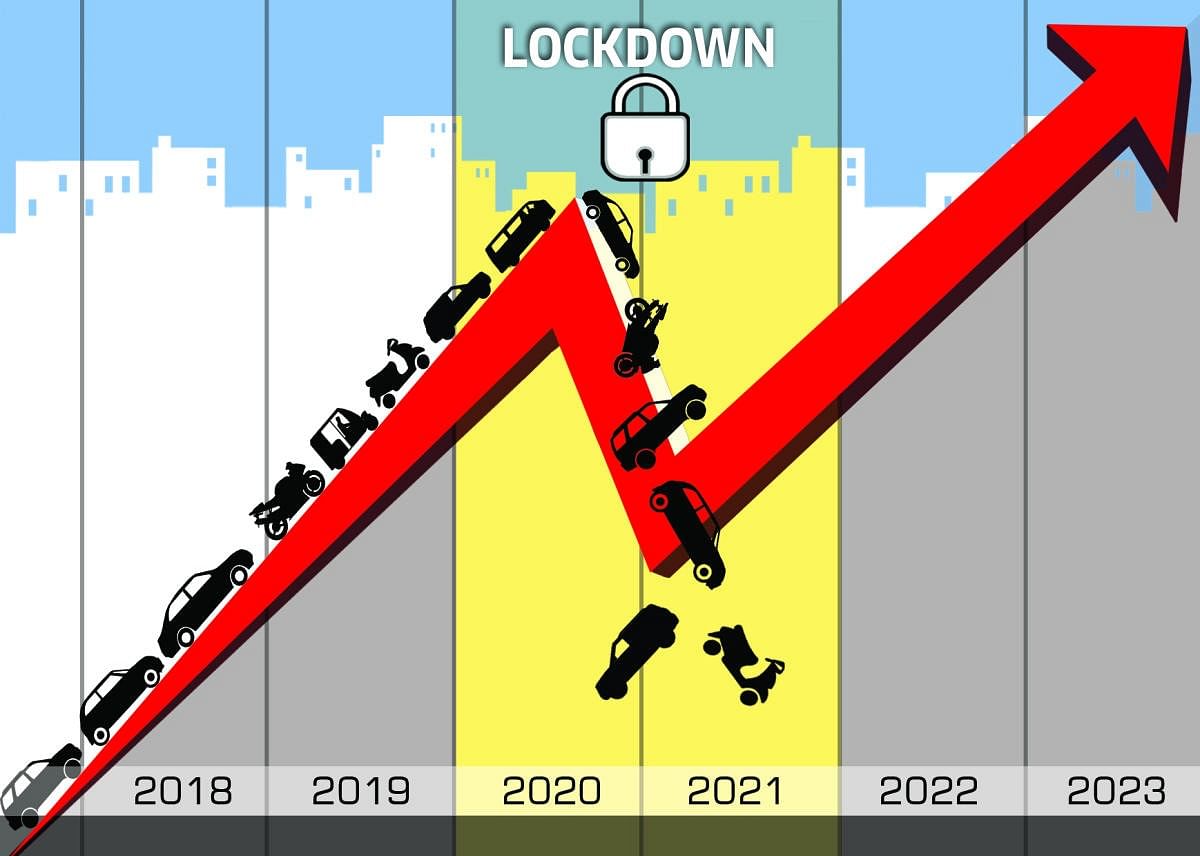

Unprecedented in over half a decade, a dramatic 40% fall in Bengaluru’s year-on-year vehicular registrations might sound musical from an eco-perspective. But this trend, triggered by multiple lockdowns and forced Work from Home mandates, could be just a temporary slump before the next big surge.

Here’s why: Wary of contracting the dreaded virus in crowded public transport options, many had switched to personal vehicles they already owned. Financial insecurity, pandemic concerns and extended closure of automobile showrooms implied they would wait before their next purchase.

Grossly inadequate to meet the daily commute needs of a city of 1.3 crore people, the public transport system is bound to be overwhelmed by the surge. But is there a way, however remote it may sound, to sustain the rare decline in vehicular sales by giving public transport a mighty push?

Unstoppable

“The real picture on vehicle registrations will emerge at the end of this calendar year. Anybody who has the means to buy will go ahead and buy. When the system is not focusing on alternate modes of commute, you cannot stop the surge,” notes mobility and transportation engineering expert Ashish Verma from the Indian Institute of Science (IISc).

Starved of funds, the Bangalore Metropolitan Transport Corporation (BMTC) has its fleet shrunk. This, when public transport during a pandemic demands more buses to compensate for the limited number of seats mandated by social-distancing. Cycling lanes, despite the efforts by a few departments, remain half-hearted at best.

Casual approach

“There is no real intent at the highest level of governance,” Verma notes. “The world over, street spaces are being reimagined. Public transport needs to be upgraded with more frequency and affordability. But the same casual, business as usual approach continues.”

Despite the rare slump in growth, vehicular numbers in the city went beyond the one-crore mark in March 2021. Industry watchers say car sales will drive the surge, and this could be bad news for congestion.

The anticipated surge in new private vehicle numbers could start once the unlock process is complete, and overwhelm the already stretched city roads. To meet this challenge, says Verma, there is a need to prioritise where the money should be spent. “The government has all the money to do white-topping on good, functional roads. It is a clear case of misplaced priorities.”

No mobility plan

Those who can afford to buy new cars and motorcycles will go ahead and make their purchases. But the lack of adequate BMTC buses has hit the workers from the unorganised sector the hardest. “While unlocking, the government should have had a mobility plan. Without buses, how will the workers commute from far-off places where housing is cheaper? They cannot walk or cycle from there.”

Post-Covid investment in public transport is extremely critical, notes Vinay Sreenivasa from the Bus Prayanikara Vedike. “Many European and American cities are evolving protocols to boost public transport. But here, there is absolutely no thinking on what kind of investment is required. BMTC has taken a huge hit in revenues,” he notes.

Since several buses have been decommissioned, the operational fleet of BMTC could be lower than 6,300 buses, contends Vinay. “They have to press the full fleet into service. Last year, after the lockdown was lifted, only 2,500 were on the roads. Waits became much longer than before, and the available buses were crowded, breaking social-distancing norms.”

Boost BMTC, not PRR

To get back its financial muscle, BMTC will have to get government support. “For this to happen, can the State defer investments in the Peripheral Ring Road (PRR) and other less important projects? Can the Centre fund acquisition of regular buses, not just electric ones?” he wonders.

Besides, at least a part of the revenue from petrol / diesel cess should be invested in public transport, says Vinay. “This is critical since there is a lot of deprivation in the urban space, be it access to work or education. There are workers travelling from Hoskote to the city centre, for instance, who cannot invest in a vehicle.”

Ultimately, the collective demand for an effective public transport system can gain traction only if the decision-making is democratised. “The BMTC MD, the transport secretary and transport minister make the decisions. The citizens, the travelling public or the BBMP are completely cut off. This should change.”