Children’s books should be simple, devoid of complex concepts, or so people like to believe. As a result, ideas of sexual orientation, gender identity and roles, which become clear to children quite early on in their lives, have rarely found space in children’s movies or books. While subtle reference to non-conformity has always existed in children’s literature (think: George from ‘The Famous Five’ series or Pippi Longstocking and Harriet the Spy), it is only recently that works that overtly challenge heteronormativity have become more accessible.

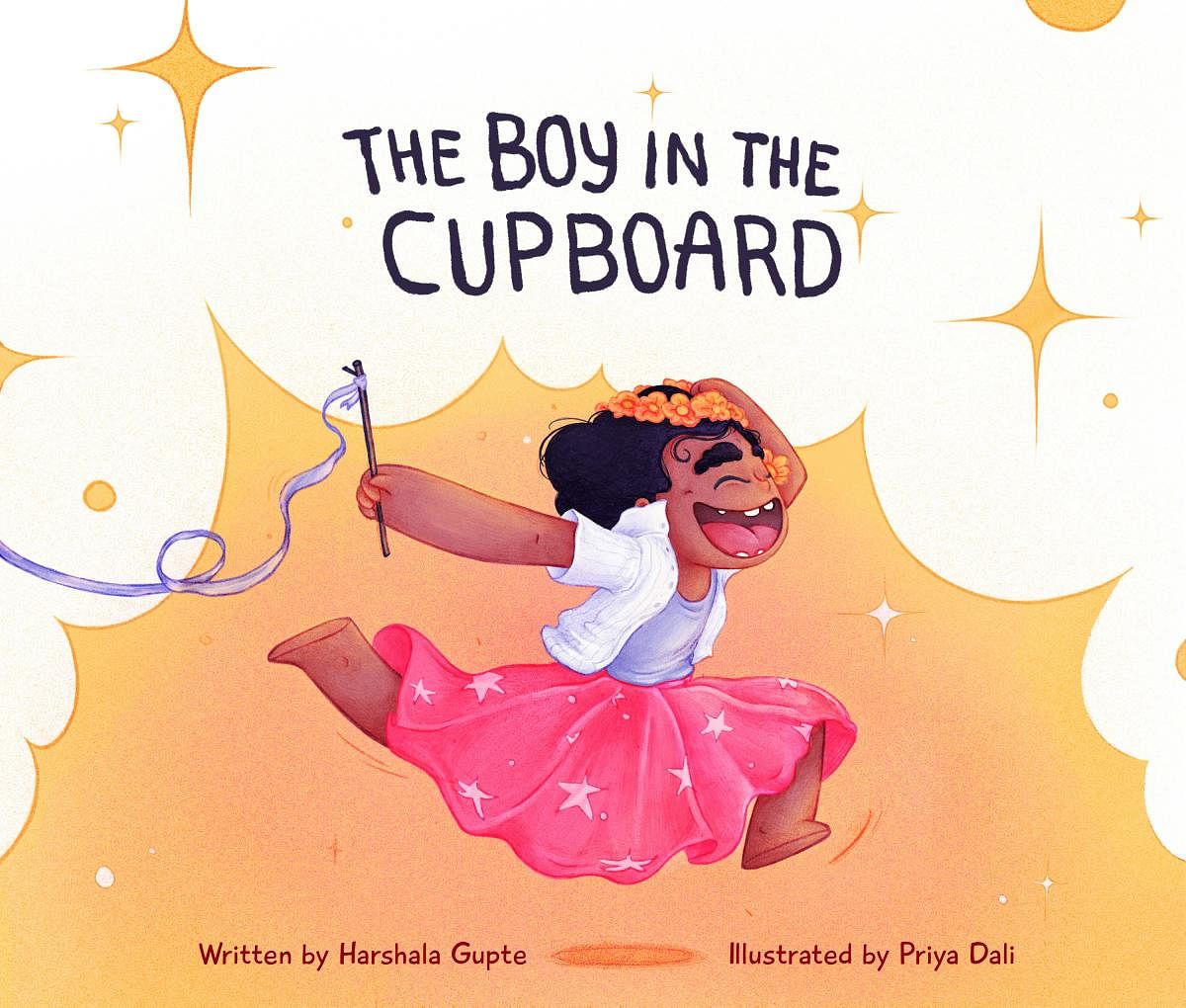

The Boy In The Cupboard’, written by Harshala Gupte and illustrated by Priya Dali, follows Karan, a young boy, who struggles to find his place in a world with rigid societal expectations. The story came to Harshala one Sunday afternoon at a cafe. She says that she always wanted to write progressive stories but the decision to write one that addresses the questions of gender non-conformity, came from the fact that the ignorance around the topic had made it one that was difficult for adults to crack, much less children. “I sat with my mother and had a series of conversations that were deep and conflicting. She barely made peace with the topic, but what the attempt made me realise was that we have not developed a language around these ideas that makes it easy to have these conversations or even simplify it,” she explains.

Breaking down barriers

Terms such as ‘cisnormativity’ are not only extremely mature but not representative of everyday realities, which makes it difficult to break it down to young ones. Apart from the clear dearth in language, the lack of colloquialism, she says, was yet another trigger. “Take phrases like ‘being in the closest’. Or, the environment within which you see stories about coming out. I wanted to bring these concepts closer to come, as opposed to existing in a world apart from ours,” she explains.

Her inspiration came from people she encountered in her life, like a young boy with a pink plastic bag once and a second-grade student who was ostracised for having hairy arms. “The narratives that exist have been internalised and that is where the behaviour stems from. You can chastise and reprimand for bad behaviour, but that only does so much. We need to create recognisable representation to break those narratives,” she says.

One size does not fit all

Inclusion is an umbrella topic and does not have to focus solely on ideas of sexual orientation or sexuality. “It can be tackled in a broader way, like the book does, by talking about gender roles. Sexuality comes later. Many young adult works, since they cater to a more mature audience, discuss these ideas. But for children, the start point is kindness, acceptance and breaking gender norms,” she says. For this reason, Karan was not given any kind of labels and was simply a book about a boy who has interests that did not fit quintessential ideas of what boys like.

For illustrator Priya Dali ‘The Boy In The Cupboard’ is not her first attempt to bring queer themes to young readers. In 2020, she wrote ‘Maya the Warrior’ a wordless picture book, which was loosely based on personal experiences. “I was always that odd kid who didn’t look or act “like a girl” and felt pushed into trying “girly” things when I wanted to be doing all things. I tried to base the story and its visualisation loosely around the feelings of confusion and something not fitting right,” she says.

Knowing of her mother’s childhood adventures was what helped her feel okay with the version of childhood and femininity she was living. “I wanted Maya the Warrior to serve as a reassurance, as proof, that liking diverse things and being curious was normal and okay,” she says.

Why queer themes?

Bengaluru-based publishing house, Pratham Books, has been responsible for producing books like ‘Friends Under the Summer Sun’ and ‘I Want to Ride a Motorbike’ that delves into gender identity.

They collaborate with writers and illustrators who can authentically talk about gender identity and expression as well also with sensitivity editors and subject matter experts as well as allies to read manuscripts that delve into important Social-emotional learning (SEL) themes. “It’s critical to see diversity in children’s books. After all, books are mirrors, windows and sliding doors to many different worlds — real, imagined, familiar, new. And, it’s even more important for children to see themselves reflected in books and at the same time, embrace diversity and inclusion through these stories,” says Bijal Vachharajani, senior editor, Pratham Books.

Priya agrees and says that the value of including queer themes in children’s literature is building empathy and validating a lived experience.

Books can help a child understand the world and help creators communicate a fleshed-out, visual idea of a world that might not exist yet. “Maya and Karan look like they could be the readers’ classmates. They show how in the same world, same school, same classroom, someone who is not you could be living a totally different version of what you go through,” explains Priya.

Introducing queer themes to a younger audience is not only about creating relatable representations, but also about opening up perspectives. “A storybook lets you become a part of someone else’s story and sample the world they live in and this interaction builds empathy and sets the reader on a route to become a good ally,” says Priya.

Audience reception

Many works that have taken the decision to address queer themes in an overt fashion, such as ‘And Tango Makes Three’ have faced a lot of backlash. Many expected the same from the Indian audience.

“I was always ready to reason with the conflict. I have assumed that it would not be easily accepted and that there will be parents who come back with questions,” she says. Since the release has happened only recently there has not been any backlash as of yet. Should one arise, Harshala says, that the book has been made with genuine intentions and with great sensitivity about what was being put in. “We spoke to psychologists and organisations to ensure that the content is appropriate,” she explains.

Priya, who is also new to the children’s books world, says that so far the response has been overwhelmingly positive.

“The people we reached have been receptive. They understand the need for material like this and want it for themselves and the kids around them,” she says.

Bijal says that children are very open and most prejudices they learn from adults. “We find that children love reading all kinds of stories and meeting diverse protagonists. ‘Friends Under the Summer Sun’ has over 2,456 reads and is available to read in 8 languages, while ‘I Want to Ride a Motorbike’ has been read 3,339 times and is available to read in 5 languages, so I think the numbers speak for themselves,” she adds.

Yet, at the moment there aren’t many books catering to this theme in the Indian market. However, with the growing awareness this is changing, Bijal says. The only advice she has for those who wish to write on queer themes is: read a lot and talk to your audience, who is smart, curious and open.