Toxins with diverse biochemical activities have critically influenced venomous organisms’ handling of prey and predators, and their successful evolution. The spider’s evolution through 400 million years has been driven by most of its species’ ability to secrete venom, largely comprising disulfide-rich peptides (DRPs).

Though DRPs constitute almost three-quarters of all spider venom, studies on their origin and diversification have returned largely inconclusive results. Two researchers at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc)’s Evolutionary Venomics Lab – Prof Kartik Sunagar and Naeem Yusuf Shaikh – have identified 78 novel superfamilies, or groupings of spider venom toxins, and pitched their findings as the first evidence of a common origin for these groupings.

The evolution of spider venom was also found to be influenced by how it was used – for capturing prey or in self-defence.

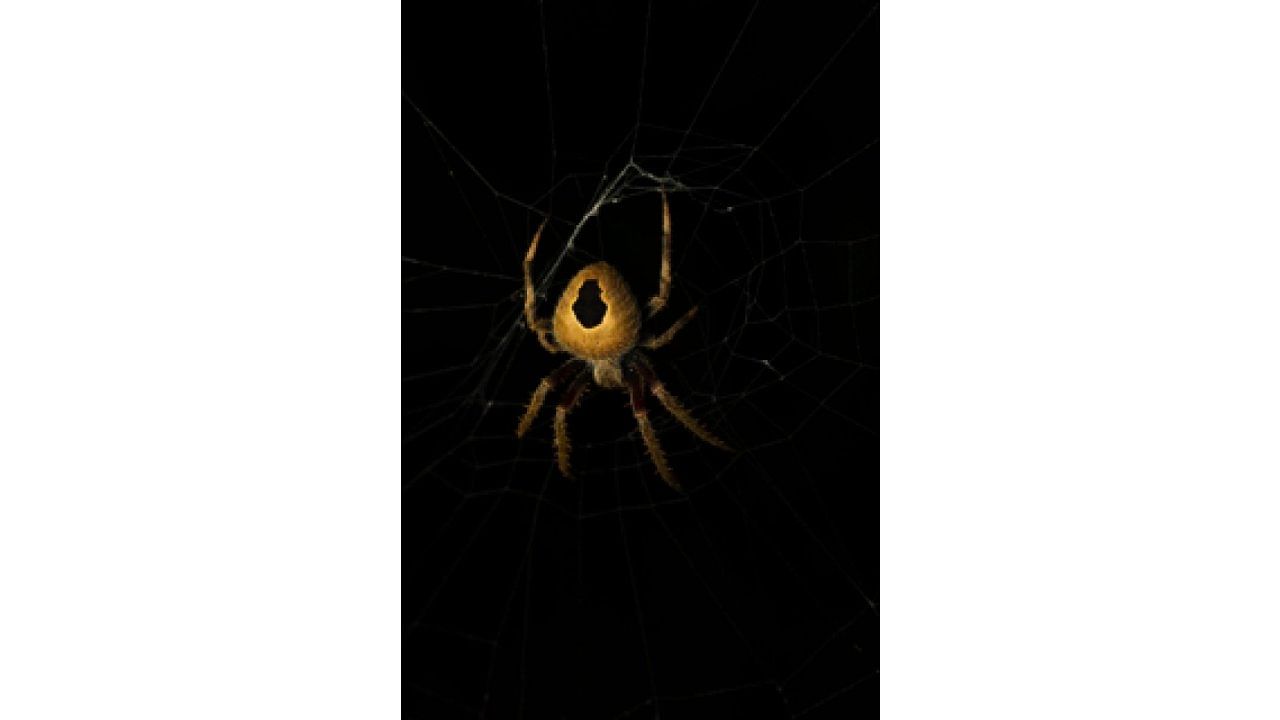

The researchers traced the origin of the toxin superfamilies to a primordial source from about 375 million years ago, in the common ancestor of all spiders, including the two infraorders araneomorphae (e.g. the web-building spiders) and mygalomorphae (e.g. tarantulas and other large-bodied spiders).

The study, published in peer-reviewed scientific journal eLife, highlighted that venoms of most other animals are composed of unrelated toxin types derived from distinct scaffolds/gene superfamilies in varying proportions.

“...instead of recruiting distinct toxins with diverse functions into their venoms like the majority of venomous animals, spiders seem to have diversified a single molecular template to generate a commensurate functional diversity in their venoms,” the study said.

“Unlike in the snake species, say, in cobras and vipers where the diversity in toxins comes from different gene families, the diversity in these spider toxin superfamilies comes from one molecular scaffold. The findings apply to the lineage of almost 70% of known spiders,” Prof Kartik told DH. The difference in venom-use strategies may have influenced the manner in which these superfamilies diversified, the study found.

It underlines a ‘two-speed’ mode of venom evolution where the offensive toxins amplify their functional diversity to gain an evolutionary advantage over prey. “The defensive venoms, since they are used less frequently, show less diversity and have largely conserved their structures over millions of years,” Prof Kartik said.

The source template has been named Adi Shakti, after the creator of the universe, according to Hindu mythology. The 78 novel toxin superfamilies have been labeled after deities of death, destruction and the underworld from across cultures – Indian, Greek, Aztec, Egyptian, Germanic, Norse, Roman, Japanese, and others. A toxin grouping described from the Agalena spider genera, in the araneomorphae suborder, has been named Panjurli after the boar spirit deity which was a recurring motif in the 2022 blockbuster Kantara. The other names on the list include Kali and Yaksha, Apophis (Egyptian), and Fenrir (Norse). “Existing venom research has not explored the diversity in spider venom lineages. Undertaking biodiscovery research on these venoms can help in identifying compounds that are of therapeutic utility to humans,” Prof Kartik said.