The brutal killing of a female tiger in an Uttar Pradesh reserve was widely shared online and played up by the visual media recently. However, a broader consensus on how to curb such savagery was not a priority.

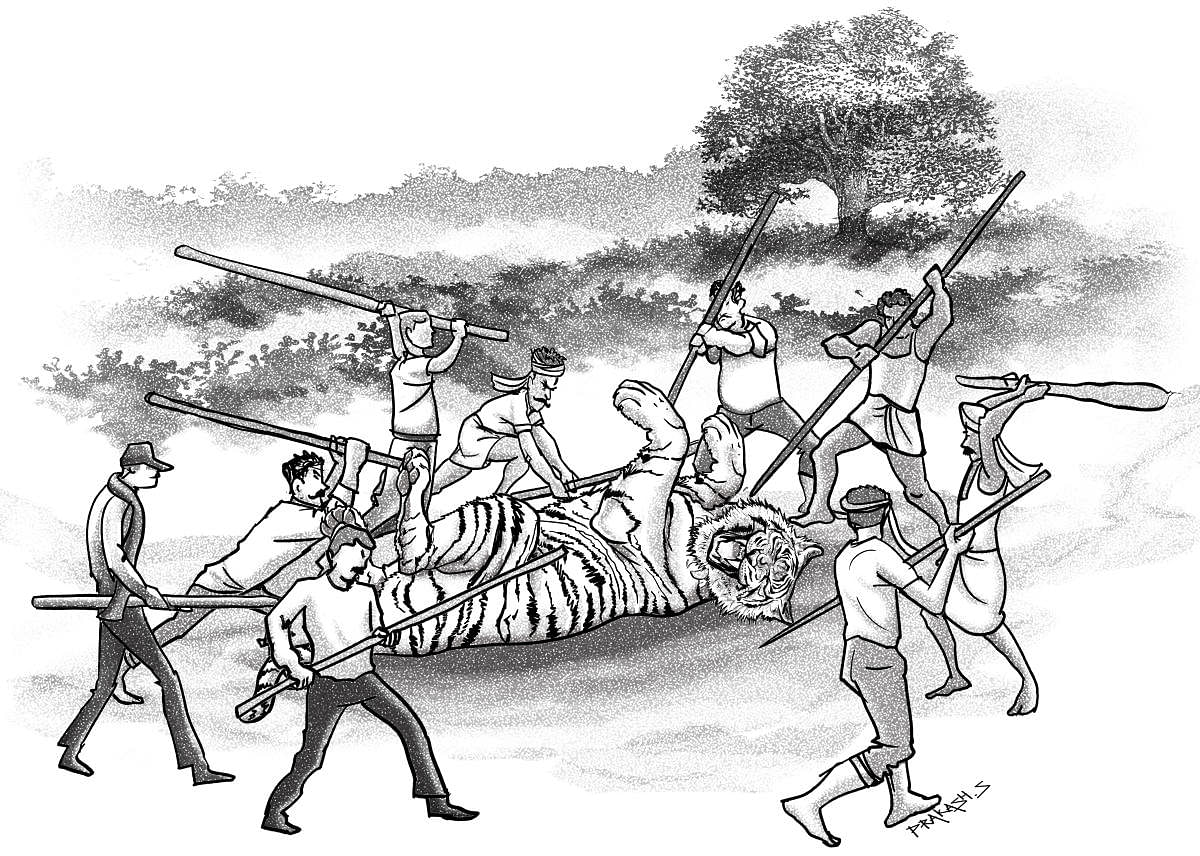

The clip had an uncanny resemblance to the climax of a barbaric tiger hunt from the British Raj, where ‘native’ trackers helped secure trophies for their masters, especially tigers.

“The death of the female tiger is tragic and unfortunate. As spaces for large iconic wildlife such as tigers and elephants shrink, the retaliation against wildlife for losses of property, crops, livestock and human life will continue to rise in India unless we address it. Our research shows that India is among the highest conflict-prone countries with an average of 80,000-1 lakh incidents a year,” reveals Dr Krithi Karanth, chief conservation scientist at the Centre for Wildlife Studies.

The majesty of the national animal was desecrated when the female cat succumbed to the sticks, poles and bludgeoning of villagers in Uttar Pradesh’s Pilibhit.

“With economic growth, social tolerance towards wildlife is drastically changing. Not just with tigers, but with leopards, elephants and other wildlife. We are seeing retaliatory killings of leopards with an increase in encounters or at times of perceived conflict. At the mere sighting of a large carnivore, people demand capture. We need to pro-actively work towards mitigating human-wildlife encounters. Otherwise, conservation of conflict-prone species will be a tight-rope walk,” says wildlife biologist and author of Second Nature Sanjay Gubbi.

Our treatment of wildlife and the patronising, piggy-backing on the recent cat census that show feeble signs of progress, and primetime programming to flavour it, in fact, does hold a mirror to the hypocrisy and rot.

“Longterm conservation should be the goal. Common man should not be affected. Communities in conflict should be brought to mainstream. It shall be a slow process no doubt. We have worked with three villages inside the Nagerhole reserve. Yet there are settlements inside. We have also worked extensively in the Bhadra Wildlife Sanctuary,” says former chief wildlife warden C Jayaram.

According to Jayaram, projects should not bifurcate habitats. “Forests and animal corridors existed even before roads. We have the first right. But, animals do too. We regulate traffic traversing Bandipur for at least nine hours everyday. We have to learn to accept inconveniences,” reminds Jayaram.

Perhaps the way we see human-animal encounters is wrong. It is only a conflict from our perspective. Not for the tiger. Our contextual sense of superiority must take backseat with animals that play a vital role and have lived for aeons without any help whatsoever from us.

“The government, NGOs and individuals have to play a key role in the recovery of conflict-prone wildlife reserves. The primary challenge is to create space for wildlife which is not impinged upon by infrastructure such as roads and railway. Mitigating conflict on the edges of reserves with human

settlements within, through compensation, insurance and other redressal is crucial. Building tolerance among people and reducing retaliation against wildlife is what our Wild Seve programme around Nagarahole and Bandipur reserves has done over the last four years. We have assisted in filing over 14,000 claims for losses of wildlife,” adds Dr Krithi.

“Pressures on tiger habitats need to be reduced as it cannot permanently take degradation. India can afford alternatives to save the national animal. Infrastructure can be at alternative locations, not in wild habitats. There are ecological, legal, economic, and more importantly, ethical reasons to save tigers or any wildlife,” explains Gubbi.

Wildlife is a larger part of our existence and evolution. We have to find a way first, not behave brutally without afterthought like we did in Pilibhit.

“A recent economic evaluation of the Bandipur Tiger Reserve has shown that it can be assigned an annual monetary value of over Rs 6,400 crore. The study also says the value of water it contributes to the Kaveri river is worth over Rs 2,067 crore a year. Is this not an enormous contribution to our farmers? For political leaders who look at wildlife as economic resource, aren’t these figures good enough to support conservation?” asks Gubbi.

So what’s the way forward here? Whatever it is, communities must not be uprooted from their lands, but integrated to minimise conflict.

“It has to be a combination of approaches. One key problem is poaching of prey which needs to be addressed through law as it is not a livelihood issue in most parts of the country, except in Andaman and Nicobar Islands. But with issues like firewood gathering, which is a key energy need for many forest-dependent communities, we need alternatives. Besides, we need to evaluate the solutions too,” feels Gubbi.

The innate tendency of the moneyed to grab land, that too forest land, must be reined in. We have plundered enough, driving the communities deeper into the forests and large carnivores ever closer.

“Gazetting reserved forests as protected, taking into account existing human settlements, as per law, is one way. Diluting of wildlife and environment laws has to come to a halt. Economic development should not cost us the country’s environmental heritage,” notes Gubbi.