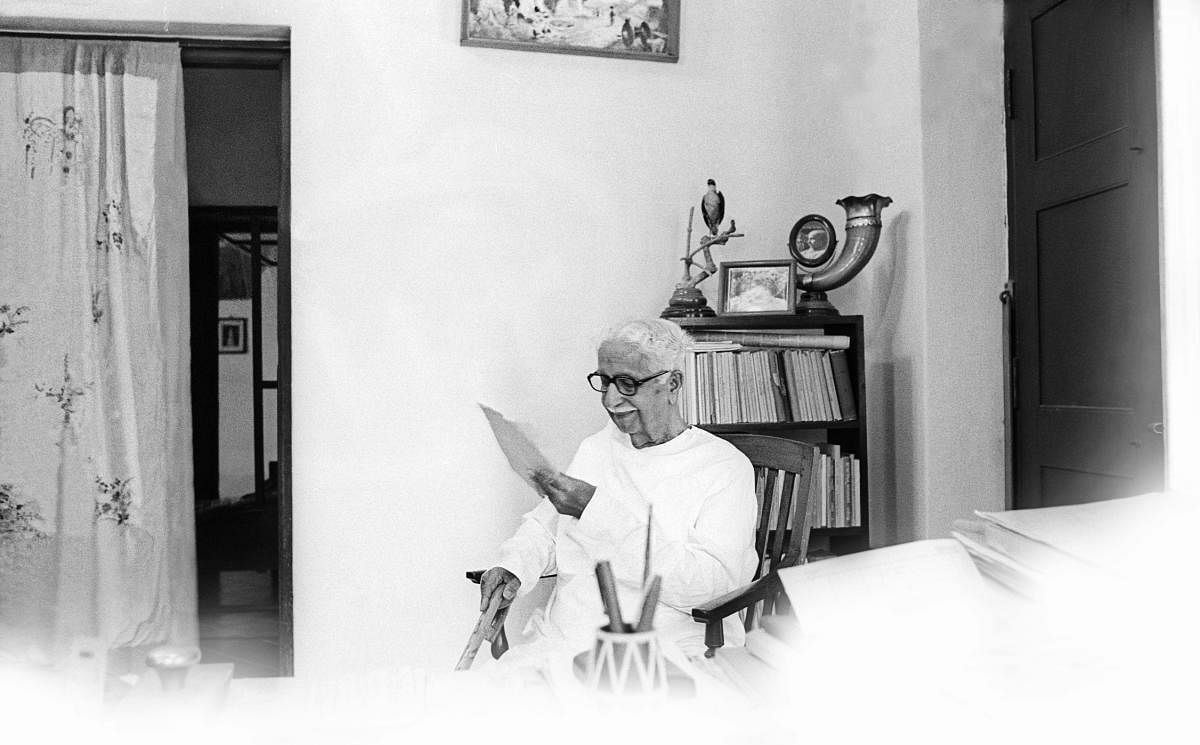

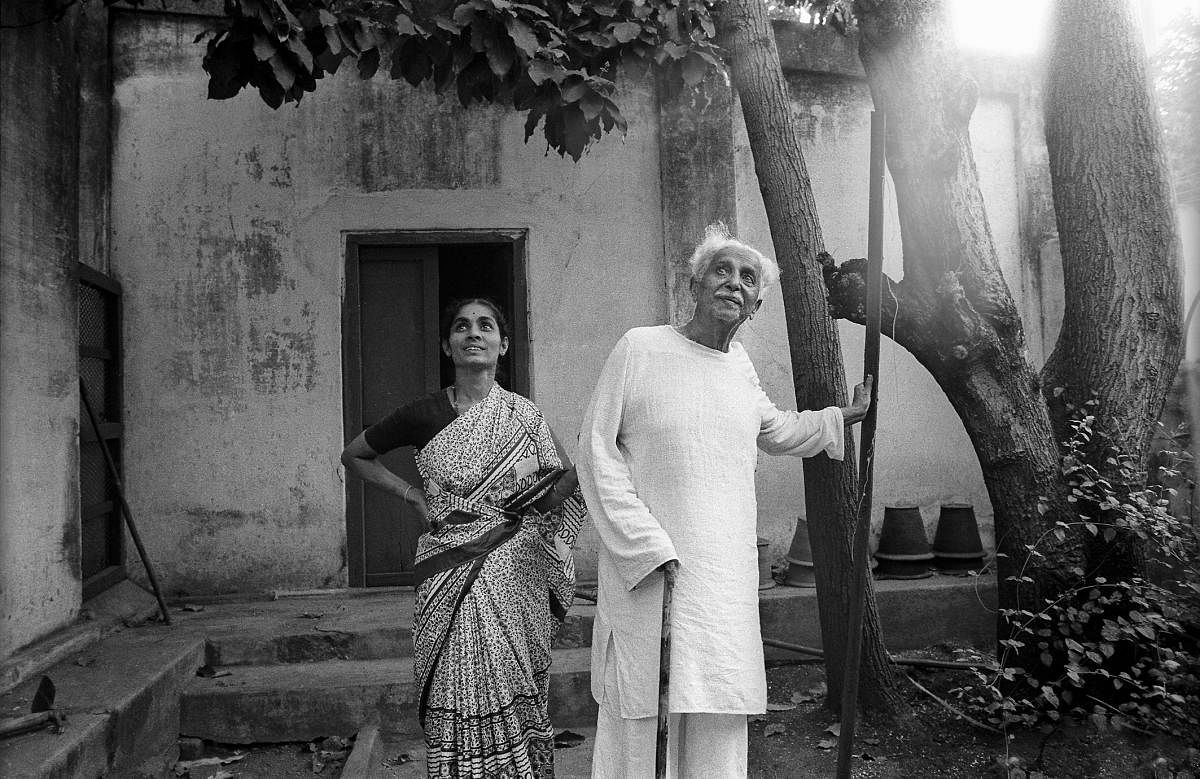

Kuppali Venkatappa Puttappa, known by his pen name Kuvempu, brought the debates of his time alive with his writings. From the unification of Karnataka to negotiation with colonial modernity and the construction of Kannada tradition as a discipline of knowledge, Kuvempu’s literature is both a record of the past and a lens for the future.

Issues related to class and caste were of great importance for Kuvempu, who came from the feudal society of Malnad. The region was in the throes of a transition towards modernity, facilitated by new education, Christian missionaries and the introduction of hotels and hospitals.

His sensibility was also informed by his time in Mysore — as a student of Maharaja College and a resident of Ramakrishna Ashrama. With these institutions, Mysore was a meeting ground of modernity which housed the rise of the Kannada consciousness and witnessed the institutionalisation of Kannada studies. The spirit of social reform influenced by Gandhi, the nationalist movement and, in Kuvempu’s case, socialism influenced by the Russian revolution deeply impacted his ideology.

As a student, Kuvempu wrote and published poems in English. He was chided for doing so by J H Cousins who advised him to write in Kannada. Kuvempu was therefore a complex and extraordinary product of the Indian renaissance.

He took the knowledge that English had to offer while also delivering a blistering critique of the language as a vehicle of colonialism. The poet had declared that if it were not for English, he would have been condemned (as a Shudra) to clean vessels in a Brahmin’s house. However, he also appealed to universities in the state to stop the slaughter of young students at the ‘guillotine of English’.

Unfortunately, the current perception of Kuvempu as a reclusive modern-day rishi — a poet whose great work was the retelling of the Ramayana — has obscured the fact that he was a progressive individual. He was a rationalist who believed in the validity of modern science and was a caustic critic of blind beliefs, inhuman and inegalitarian traditions. He believed that the Upanishads contained timeless truths. At the same time, he believed that nothing should be accepted without intellectual scrutiny.

Kuvempu made the distinction between mati (reason and rationality) and mata (sectarian belief or dogmatic knowledge based on false understanding). Mata is illusionary and misleading and mati is the power of intelligence. ‘Nooru Devaranella’, his famous poem, is a clarion call to ‘reject hundreds of sectarian beliefs in order to become fully human.’ Even as a young poet, he urged students not to humiliate themselves by going to temples where they would be unwelcome because of caste discrimination. Instead, he encouraged them to find the divine in nature.

Many decades later, when the poet was in his seventies, Kuvempu offered a pungent critique of a religious philosophy which placed human souls on a hierarchy. But this, he cautioned writers, did not mean that tradition must be renounced altogether. “You do not throw away family heirlooms because of their outdated design. You smelt the gold and make new jewellery,” Kuvempu said in his inaugural speech at the Association of Writers and Artists.

His belief in rationality was so sound that even in his thirties, the poet told the youth that, “even if the four-headed Brahma were to appear and declare that he had dictated the Vedas, you should not nod your heads in agreement.”

Characterised by his interviews and the memoir written by his son Poornachandra Tejaswi, Kuvempu was a forthright, articulate, passionate commentator on democracy.

His views on the country’s progress after independence are evident in the convocation speech he gave at Bangalore University. In the speech, he condemned the suicidal effort of the nation to imitate the western model of economic progress and the subsequent abandonment of Gandhi’s principles of truth, non-violence, Swadeshi and grama swarajya. In a prophetic manner, he described the corrosive sectarian ideologies which threaten the values of tolerance and co-existence — a matter relevant to this day.

Another metaphor, one that reverberates even today in literary and cultural circles, is that of the priestly classes representing a tiger. This tiger, he said, has to be shot dead with a powerful gun. In this strange hunt, however, the gun should take aim not at the tiger’s head but at our own — signifying the need to rid ourselves of idolatry, which has enabled this hegemony. Of all the great modern Kannada writers, it is Kuvempu who has been an interlocutor and a contemporary of younger generations.

(The writer is a literary and cultural critic based in Shivamogga)