Every weekend, a diverse group sits on the floor at a community space in Mysuru, learning how to spin cotton yarn. Over the last 15 months, the city has been witnessing this unique experiment in sustainable clothing. Called noolugarara balaga (spinners group), the collective is enabling people to be more involved in the process of making clothes.

Given that India produces about 9% of the world’s textile waste, the initiative is aimed at generating employment, reducing the carbon footprint in garment creation and encouraging slow consumption.

Around 150 people have been trained in spinning through workshops organised by the collective. Once the skill is picked up, these individuals spend an hour spinning cotton every day in their homes.

If one person spins for an hour daily, they can produce about 60 to 70 metres of fabric in a year.

“If 100 people spin for an hour every day, five weavers get employment throughout the year. Similarly, tailors and dyers also get work,” says Santosh Koulagi of Janapada Seva Trust in Melukote, which has been running a weaving centre for the past five decades. Additionally, the weavers do not have to worry about finding a market, leading to a closed-loop economy.

The seeds of the spinning initiative started in the Seva trust’s weaving centre last October.

K J Sachidananda, an artist from Mysuru, saw Santosh spinning the charkha on a visit to Melukote. “It seemed magical. I felt an urgency to learn it and start spinning,” he says.

The activity compelled him to begin his mission to popularise spinning in urban areas. Workshops, training and interactions have all helped take the idea beyond Mysuru.

“Though people take interest initially, not many continue because it requires commitment and practice. Considering this, 150 people trained is a good achievement,” says Santosh.

Workshops are held at a community centre every weekend in Mysuru. Those interested can continue until they learn how to spin the charkha.

“There is a learning curve. Some pick it up fast, some take time to get into the flow. People need a push until they get their first cloth done,” Sachidananda says. Then, the allure of the charkha keeps them spinning.

Connected

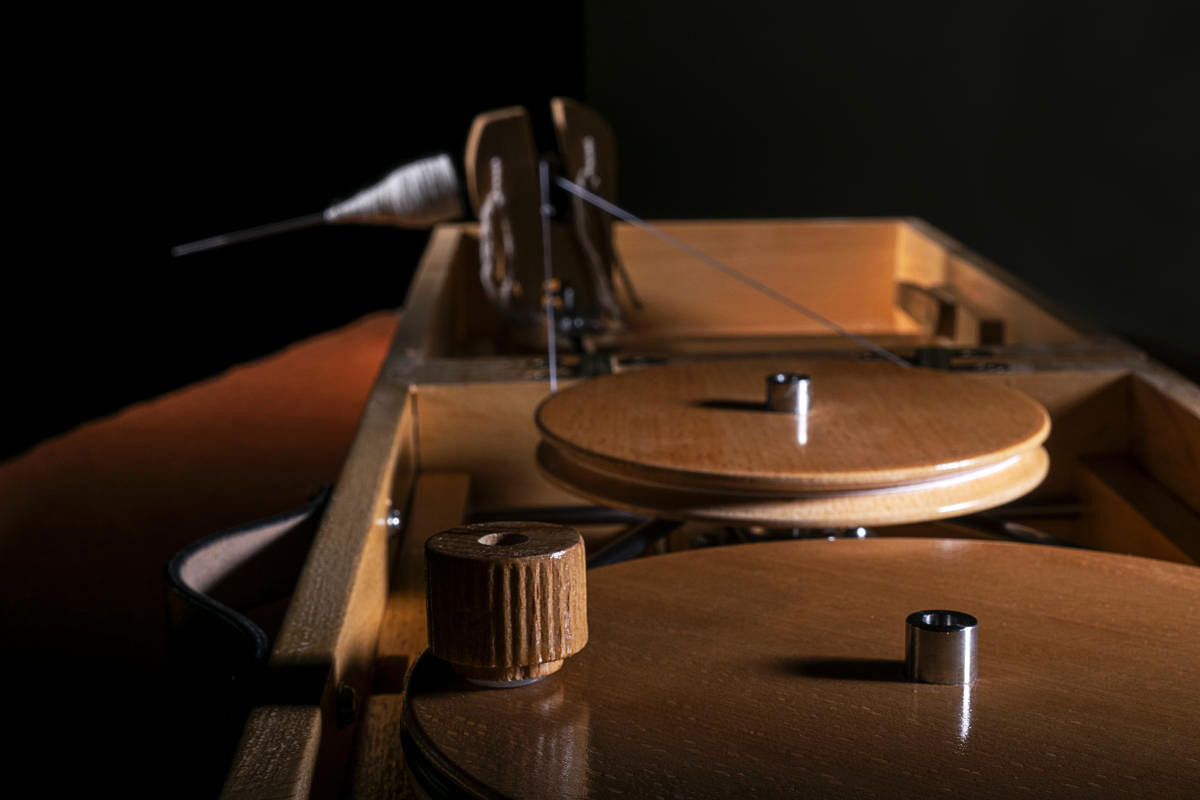

Initially, the group tried spinning with box charkhas sourced from Wardha in Maharashtra. Eventually, the team tied up with a manufacturer to develop box charkhas in Mysuru.

As many as 170 charkhas have been sold now. These charkhas are sold with the condition that they must be used.

Taking note of the initiative, Baala Balaga school in Dharwad, organised a three-day workshop in the school. They started with higher classes and now students until Class 6 are involved in the activity for an hour every week.

“There are so many things that we can teach through charkha. We can teach maths, physics, biology, history and geography, water consumption to the history of our freedom struggle,” says Pratibha Kulkarni, principal of Baala Balaga.

“At the end of the year, our dream is to stitch a shirt for the child from the yarn they have spun. This might happen next year,” she adds.

Avani and Khushi, students in Class 9, consider spinning unique, and different from other craft activities. Their fascination increased when they were able to complete what they thought was a tough task. “The yarn is sent to a khadi-making unit in Dharwad. Once there is sufficient quantity, we will get fabric made of the yarn we spun,” Khushi says.

For Class 10 student Rishi, spinning has helped improve eye-hand coordination and concentration.

Sumana, an educator, and her eight-year-old child Maya, joined the Mysuru spinning group two months ago. They had a similar observation.

“Spinning automatically leads to concentration. I was a bit apprehensive about my skills. Even my daughter showed interest and she learnt spinning in a month. Of course, it requires regular practice,” she says. Now, Maya is able to spin for 30 minutes at a stretch and both mother and daughter are partners in spinning.

Like many other members, she says that the journey of sustainability can not be forced. “When you begin this journey, you feel that it is a lot of hard work. It is the process and end product that will sustain interest,” says Sumana.

The members feel that this helps them do their bit to support rural livelihoods and responsibility towards society.

The group is also made aware of everyone involved in the cycle of making clothes — from spinners to weavers and tailors. Weaver Savitha K in Melukote, for example, feels that it is difficult to weave fabric from handspun yarns as it is not fine, “but I am happy helping them. It is a beautiful thing when consumers are part of the production as well,” she says.

The group ensures not only traceability but is also an opportunity to impact livelihoods directly, and positively.

“The whole process makes us responsible consumers. We do not discard a cloth in which we have invested so much time and passion,” says Sachidananda.

Sachidananda can be contacted on: 82774 17878.