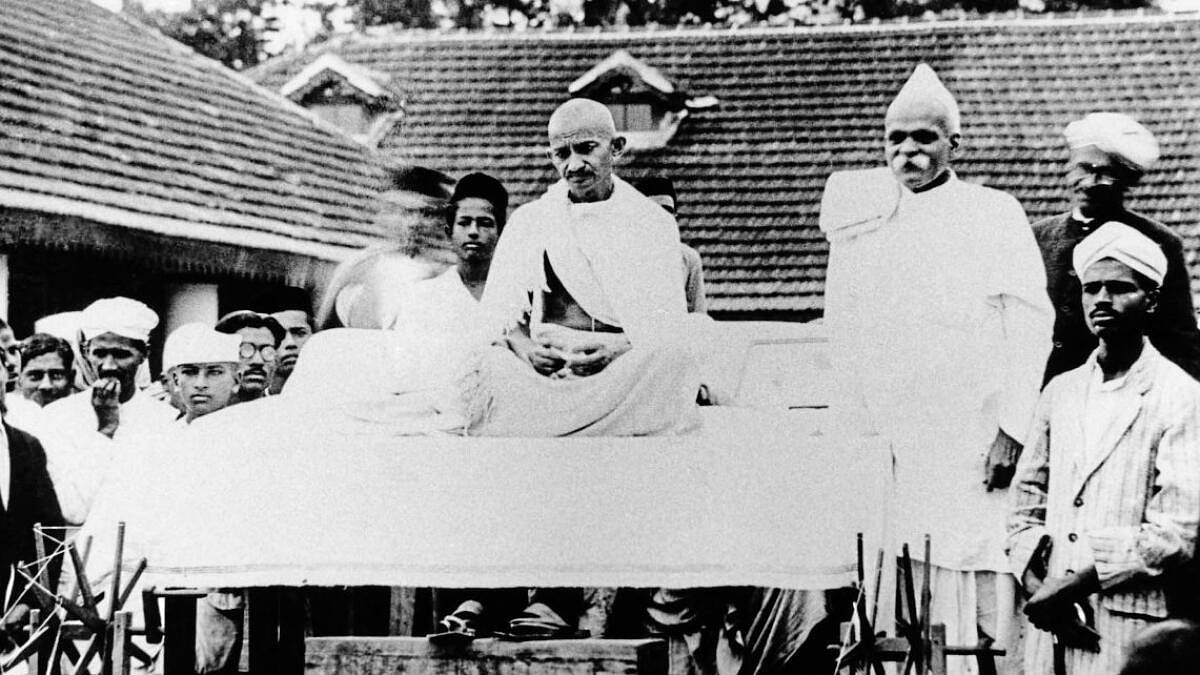

Mahatma Gandhi addresses a meeting at the district collector’s office premises in Chikkamagaluru in 1927.

DH Archives

Close to midnight on August 15, 1947, Kuvempu, the epoch-defining Kannada writer, was listening to the festive sounds of the first Independence Day on All India Radio. Swatantryodaya Maha Pragatha, an ode, was taking shape in his mind. Suddenly, the poet turned morose, as he realised the father who had led the freedom struggle was not there. He sighed: “Where is he? He, the father, who led us holding our hands…”

By then, young Kuvempu had written several lyrics inspiring people to join the march for freedom. For him, Bharatambe was the unifying force in a land of diverse gods: ‘Shove those hundred gods away/Come, let us worship Bharatambe now.’

Shivaram Karanth took part in the freedom movement, and in his early novel Chomana Dudi, Choma, the Dalit labourer, longs to own a piece of land and become an independent farmer. Karanth’s Marali Mannige deals with the freedom struggle, while Naavu Kattida Swarga laments the disillusionment that followed.

Bendre wrote intense lyrical poems urging Kannadigas to plunge themselves into the freedom struggle. His poems, Tuttina Cheela and Narabali took a dig at the colonial government. In fact, Narabali landed him in jail. Gorur Ramaswamy Iyengar too was jailed during the Quit India movement. He translated Gandhi’s autobiography into Kannada, and in his novel Hemavathi, the Brahmin protagonist marries a Dalit girl at Sabarmati in the presence of Gandhi.

In fact, the freedom movement has been revisited, and the freedom metaphor redefined, in all phases of modern Kannada literature. Ideals like inclusive secularism, village-centric vision and the social responsibility of writers were drawn from the freedom movement too.

Pragatisheela writers in the ‘50s, Basavaraj Kattimani and Niranjana, were drawn to the freedom movement, which provided themes and perspectives to their novels. Kattimani’s Maadi Madidavaru invokes Gandhi’s clarion call ‘do or die’, and tells the tale of the Quit India movement in Karnataka. Socialists and other revolutionaries went underground and sustained the spirit of the August Revolution (the launch of the Quit India Movement). Maadi Madidavaru captures the spirit of the August Revolution and records the sacrifice of the common folk who have no place in the annals of history.

Niranjana, a Marxist writer, revisits the Kayyur farmers’ uprising in Kerala and narrates the inspiring tale of the revolutionary youth and their teacher who led the farmers’ revolt and were hanged by the British government.

M Jamuna, the feminist historian, discusses some interesting images from the freedom movement found in the professional theatre space. She cites a scene from Kurukshetra which defines Krishna as Gandhi. The Company Theatre presented Tipu as a true freedom fighter, who pledged his children to the British and fought a royal battle. Kannada theatre awakened the masses during the freedom movement and continues to play a similar role.

Disillusionment sets in

By the mid-60s, the Navya writers were disillusioned, as they watched the decline of values in public life. Gopala Krishna Adiga, who wrote poems like Kattuvevu Naavu (we will build) during the freedom movement, later wrote poems filled with images of despair.

Many writers of this generation became bitter critics of post-independent India. P Lankesh, Poornachandra Tejaswi and U R Ananthamurthy were drawn to Rammanohar Lohiya, the socialist thinker and leader. They turned out to be bitter critics of the Nehruvian era.

Tejaswi’s story Tabarana Kathe exposes the heartless bureaucracy: Tabara, a peon in a government office, runs from pillar to post to get his pension, but to no avail. Tabara praises the British on the eve of the silver jubilee of Independence Day, as people dub him mad.

Ananthamurthy’s novel Samskara captures an interesting fallout of the freedom movement in a sterile agrahara. Naranappa, the Brahmin rebel, stirs up the agrahara and warns the conservatives of his village: ‘Congress will come to power. You will have to allow Harijans into your temples.’

Women’s voices

Women who started writing during the freedom movement defined the concept as the freedom of womenfolk in general. They started writing about the liberation of women from the clutches of conservative Hindu Society.

Some of them responded to political developments. Haadina Venkamma, who was in her teens when Bal Gangadhar Tilak was jailed, wrote a poem praying for his release.

Nanjangud Tirumalamba, who was widowed in her teens, took to writing. She went to Delhi and stood in the crowd of women who hailed B R Ambedkar when he walked towards Parliament to present the Hindu Code Bill. She waited on the lawns of Parliament, and wept when Ambedkar announced his resignation as the Bill to provide property rights to Hindu women was rejected.

In post-independent Karnataka, women’s literature has often defined the idea of freedom as the freedom to rebel, to question, to resist, to emancipate, to choose and so on.

Siddalingaiah, the pioneer of Dalit poetry, wrote Freedom of 1947, a poem that spelt out where ‘freedom’ came, and to whom: To the pockets of billionaires, boots of the police, whip of the landlord and bullets in the gun. Echoing Siddalingaiah’s ire, the Dalit Sangharsha Samithi observed Independence Day as ‘Black Day’. Dalit activists held marches carrying burning torches at midnight on August 15 in the ‘80s.

Bandaya poetry examined post-independent India quite critically. Towards the end of the 20th century too, novelists invoked the spirit of the freedom movement. Balasaheb Lokapur drew metaphors from the movement, while Nagaveni’s novel Gandhi Banda (Gandhi arrived) examined from a feminist angle the churning that Gandhi’s arrival heralded in the closed societies of Dakshina Kannada. Bolwar Muhammad Kui’s Swatantryada Ota revisited the freedom movement in the 21st century, while B L Venu’s novel, Durgada Bedara Dange (2021), narrates the revolt of soldiers of the Beda tribe in Karnataka, which happened much before the sepoy mutiny.

Kannada intelligentsia critically examines the idea of nationalism. D R Nagaraj and Banjagere Jayaprakash have critiqued the rhetoric of nationalism and demonstrated how Kannada culture evolved an inclusive nationalism. The freedom movement and the freedom metaphor continue to inspire and ignite the imagination of the Kannada writer even today.

(The author is a short story writer, playwright and a cultural critic)