Aruldas and Sathyarani, talented artists born in the Ragigudda and Koramangala slums of Bengaluru respectively, epitomise the vibrant cultural creativity thriving in urban slums. Arul, through his powerful poetry, soulful songs, collage-making, and painting, educates children and youth, and also mobilises communities in slums to demand basic services, land rights, and pro-people amendments to slum laws.

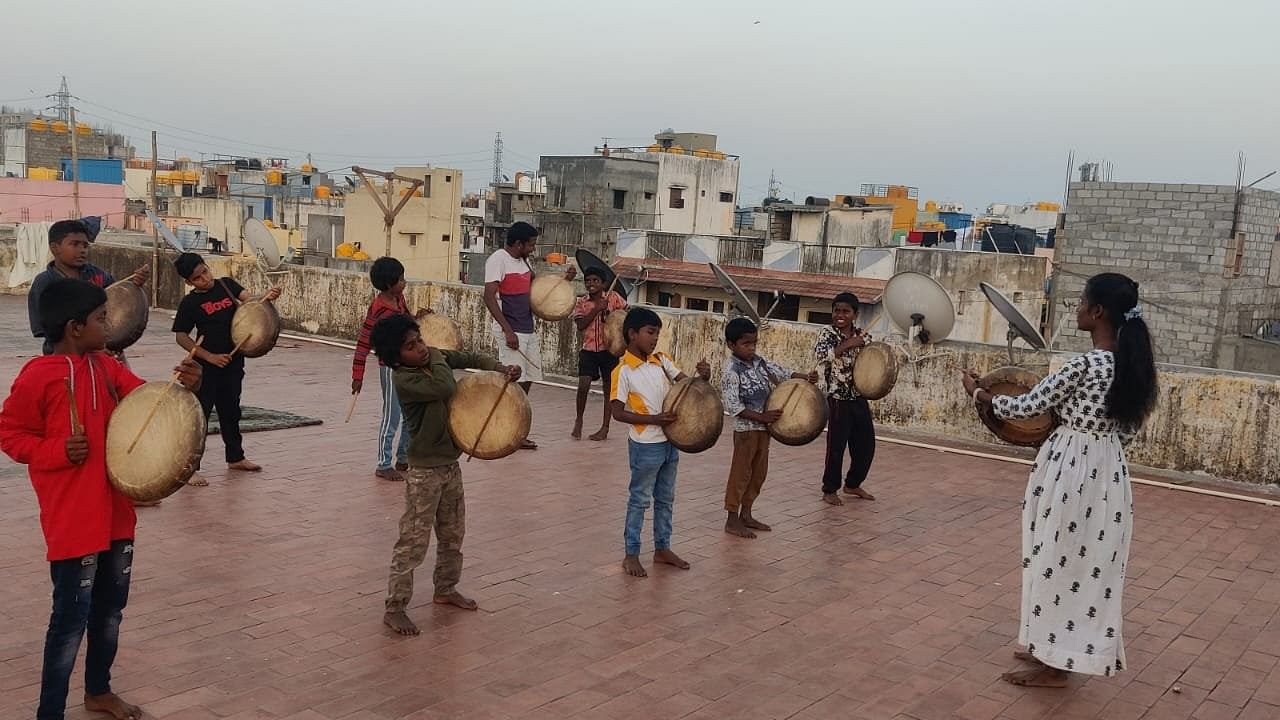

Sathya, the leader of a cultural group named Big Bang, uses art to connect with both local and global audiences, blending traditional South Indian instruments with African beats to create powerful performances. The group functions under Maarga, a community-based organisation that works in slums.

This vibrant cultural atmosphere is not unique to Arul and Sathya’s stories, but is a hallmark of life in slums. Children growing up in slums are constantly exposed to song and dance, with not a single day passing without some cultural event. With this level of vibrancy, slums are bustling hubs of artistic expression, where creativity becomes a tool for advocacy and change.

Aruldas at a performance in Bengaluru.

These urban landscapes showcase rich tapestries of music, dance, art, and storytelling that reflect lived experiences, struggles and aspirations. Slum residents, in many cases, are migrants seeking better opportunities, who face systemic injustice, including a lack of physical security, inadequate housing and basic services, social stigma and economic exploitation. However, they demonstrate a boundless capacity for cultural and social transformation, which deserves recognition as an "urban folk" genre. This classification acknowledges the distinctiveness and significance of their socio-political and cultural realities and highlights the transformative potential of cultural movements for emancipation.

Defining an ‘urban folk’

Rural folk and urban folk, while sharing core characteristics of communal creativity, spontaneity and reflection of lived experiences, differ significantly in their environments and expressions. Rural folk culture is deeply rooted in traditional, agrarian lifestyles, passed down through generations in stable, close-knit settings. In contrast, urban folk culture emerges from the dynamic, diverse, and often harsh realities of urban slums. It is a product of rapid urbanisation, displacement, economic necessity and the melting pot of various migrant backgrounds. Urban folk forms are marked by their adaptability and innovation, reflecting the fluidity and resilience of slum communities amidst systemic neglect and social stigma.

Urban folk includes rhythms, beats and mixed sensibilities of the diverse communities in slums. Take, for instance, Gaana, a genre of music that originated in the ‘backstreets’ of Chennai, and saw an increase in popularity when featured in mainstream Tamil cinema.

Urban folk comprises not just songs, but also dance, painting and stand-up comedy, with performances bringing the genre to new audiences, and the content aiming at social activism, especially against caste discrimination. Cultural activists in slums often express that formal spaces created by the government, like the Ravindra Kalakshetra in Bengaluru, for example, are inaccessible to them. “This is an institutionalised form of discrimination against Dalits and others in slums,” says Arul.

He feels that even traditional rural folk, which prides itself on being more people-oriented compared to classical genres, is averse to emerging art forms. For urban folk from slums and deprived urban locations, the ready embrace of international art forms like Zumba, hip-hop, rap and freestyle is not just a significant divergence from rural folk, it is also a deliberate attempt to bypass the formal spaces and reach out to an international audience.

“For us, art is a means of connecting to the world when even the ruling class in our own spaces ostracises us,” says Arul. This perspective aligns with Ambedkar’s view that “lost rights are never regained by appeals to the conscience of the usurpers, but by relentless struggle.” Urban folk is hence a powerful part of the struggle of marginalised communities in India.

Common features

Like traditional folk forms, urban folk culture is inherently community-based. It is created, performed and enjoyed by the community, often in informal settings. Street performances, community festivals and local gatherings are common venues for these expressions.

Urban folk culture is also marked by its spontaneity, distancing itself from the structured and formalised nature of classical forms. This spontaneity makes it more accessible and relatable to the everyday experiences of slum dwellers. It holds up a mirror to the lives of slum dwellers, capturing their joys, sorrows, struggles, and aspirations. It serves as a means of preserving collective memory and identity, offering a sense of continuity and belonging.

Arul's journey exemplifies the potential of urban folk culture. After dropping out of high school due to financial constraints, he was recognised by a local NGO for his artistic talent. With their support and training, he became an active leader in his community, using art and culture to mobilise children and adults to advocate for socio-economic and political mobility.

For Arul, bypassing local discriminatory structures and reaching out to a larger global audience is about self-respect. “An exceptional few like P A Ranjit, the Tamil film director, have the ability to use mainstream media to propagate subaltern ideas. We use other cultural forms and try to make them popular through sustained events and programs,” he says.

Cultural groups in slums from various cities in India have been connecting and hosting events. There are frequent meetings of such groups in Chennai, Bengaluru, Mumbai and Hyderabad, says Arul.

Transformative power

Urban folk sends a message that everyone can sing, dance, or paint to express themselves. “Even social media and AI are being used as channels of expression, and we are open to the new opportunities they create for us,” says Arul.

Sathya highlights the ‘tectonic theory’, explaining the “natural connection between Africa and Dalits and other deprived communities in slums of South India.” She explains how they use the tamate, a hand-held drum from South Karnataka, along with the djembe, a percussion instrument from Western Africa.

“We dance Tapanguchi for a hip-hop song sung in the vernacular, with djembe beats,” says Sathya. This blending of cultural forms underscores the vibrant, inclusive, and dynamic nature of urban folk. The parent genre of urban cultural expressions is often rap and reggae. Rap is especially popular among children to narrate their own stories of deprivation and aspirations, as well as rightful demands. Stand-up comedy performances on street corners in slums are fast emerging as a creative form of self-expression, she adds.

There have been cases when children have been able to overcome drug addiction, having found a vibrant alternative world of opportunities through these expressions.

Performances by slum groups go far beyond what meets the eye. They are deeply introspective, drawing on the messages of social reformers like Basavanna, Kabir, Shishunala Sharifa, and Mante Swamy, while also exploring contemporary liberative theories.

According to noted sociologist Kalpana Kannabiran, rupturing caste formations requires engaging with the politics of becoming and challenging traditional notions of the self. This involves de-schooling and politicising the self in new ways.

For many youth, urban folk forms are also about impacting others in the city of their existence and about reiterating their progressive identities. “Our continued existence in the Ragigudda slum as a secular and progressive community in the midst of a conservative Jayanagar in Bengaluru is proof of our resilience,” says Arul. “Our dynamic cultural forms strengthen our commitment to constitutional values of equality and justice,” he says.