A remarkable feature of the Vachanakara movement in 12th-century Karnataka was the radical interrogation of gender identity. While most bhakti traditions transgress socially approved gender roles, the Vachanakara movement not only saw the actual participation of women in the socio-cultural, religious movement, but also the composition of poetry by nearly thirty women poets from various locations.

They brought into their vachana poetry the heterogeneity of experiences, attitudes and modes of communication. While Akka Mahadevi is distinguished by unsurpassed lyricism and mastery of imagery and idiom, the other women poets employed a repertoire of styles, tones and rhetorical strategies.

Like their male counterparts, these writers take their images from the professions they practice — from kayaka (work), which was considered sacrosanct. Kadira Remavve describes the parts of her spinning wheel as the gods Brahma, Vishnu and Maheshwara themselves. In her only surviving vachana, Sule Sankavve uses details of prostitution to describe her idea of single-minded devotion to her god.

Lakkamma, the wife of Ayldakki Marayya, chides her husband sternly for collecting more rice than required. She admonishes him that greed is for the kings, not Shiva’s men (devotees). Many of the women poets are sharply critical of men who make a show of their devotion. They wonder if these pretenders are free from lust. Even while composing vachanas using the settled modes of expression, some of them raise radical questions from a woman-centric perspective.

“If a man grows fond of a woman and clutches her, that thing must be seen as another’s property. When a woman desires a man, we should know what to call this,” (from a vachana by Goggavve).

Akka makes a frontal attack on the male gaze which treats her body as merely an object of lust. There are few parallels to match the intensity with which she revolts against such forced imprisonment in the body. At the same time, without any prudery, she offers a full-blooded, fleshly surrender to her god, Channa Mallikarjuna, whom she considered as her spouse.

“If you hug/ a body, bones/ Must crunch and crumble;/ Weld/ The welding must vanish/ Love is then/ Our lord’s love.”

(This is an excerpt from A K Ramanujan’s translation of the vachana ‘Speaking of Siva’)

She warns him that if challenged, she would dress like a woman warrior, and ride a horse, blowing the horn. Elsewhere, tenderly she surrenders herself to her lord who appeared like a mendicant with alluring locks of hair and a toothy smile. She celebrates her self by endlessly reconstructing it to match the myriad forms in which her lord appears.

Gender fluidity

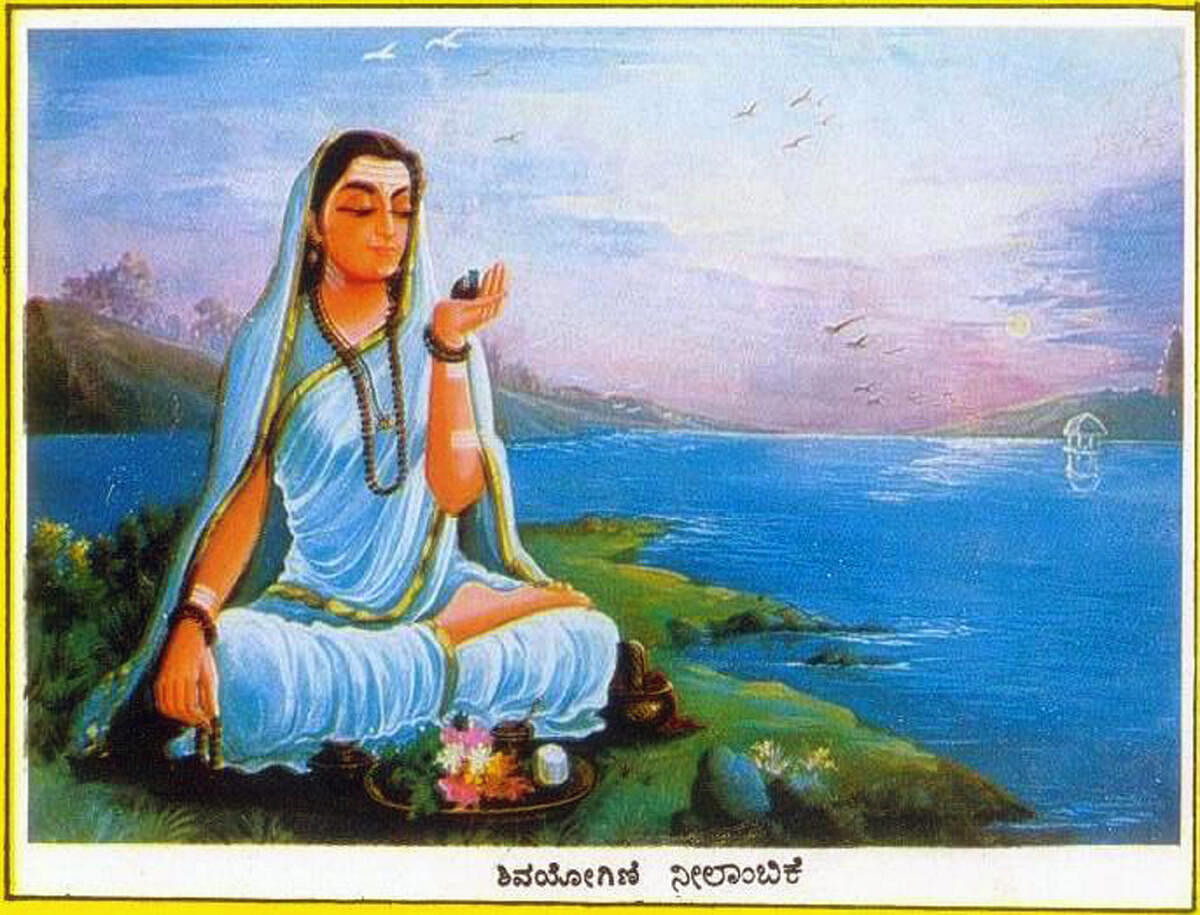

Nilambike has written remarkably about the fluidity of gender in intimate relationships. She writes: “I can’t be called Basava’s wife/ Neither can Basava be called my man/ Tearing apart the kinship of two-ness/ I became Basava’s infant/ And Basava, my infant.” (From H S Shivaprakash’s translation, ‘I keep vigil of Rudra’).

This matches with Basava’s view of gender roles when he says in a vachana: “Look here fellow, since you ask, I say I am a man. Otherwise, sometimes I am a man and sometimes a woman.”

At the same time, carnal love in a marital relationship was welcome. The religion of the Vachanakaras did not subscribe to forced celibacy and renunciation of the world. As Akka Mahadevi says and women poets agree, if you can keep desire under a leash, a self-punishing renunciation is unnecessary.

Akka Mahadevi writes: “If a female remains a female/ The male is a pollution/ If the male remains a male/The female is a pollution./ When the mind’s pollution sinks away/ Where is space for the body’s pollution.”

A desired ideal

However, emancipation from socially reinforced gender roles was not the ultimate objective. The desired ideal was conjugal love, companionship and devotion to kayaka and the community. From the 1,000 vachanas written by 33 women poets collected by the late M M Kalburgi, it appears that the women in the Vachanakara movement were not confined to the domestic world. They were active participants in the religious philosophical debates and were passionately involved in shaping the radically new religion. Their poetry reveals familiarity with the repertoire of myths, legends, religious rituals and social customs — the same from which the male poets drew.

If ‘Anubhava Mantapa’, the great assembly of the sharanas was a historical reality, then women were its articulate and independent-minded members. The evidence is found in many of the argumentative, rhetorical vachanas which possess the tone of a public debate.

The philosophical debate between Allama and Muktayakka as narrated in the Shunyasampadane (a work that compiled the vachanas and placed them in an imaginative context in which they are ‘spoken’) is among the most sophisticated debate on truth, language and silence.

Mystical experience

The vachanas of Muktayakka are a testimony to the depth of her metaphysical enquiry into the problems of representing mystical experience in language. She argues that the experience of the self uniting with the supreme reality should be like ‘the dream of an infant’ which cannot be described in language.

The women poets share the egalitarian philosophy of the movement and protest against the varna system and caste discrimination. Bontha Devi asks whether there is a Brahmin space inside the village and an untouchable space outside the village. Space (bayalu) is one and immutable. There are many women poets from the oppressed castes of the 12th-century society and they speak of the joy of transcending caste barriers. Interestingly, some of them wrote vachanas in the bedagu style. The bedagu mode of writing deals with mystical experiences using a somewhat dense allegorical or metaphysical register. This is close to the Ulatbhashi or Sandhyabhash mystical style employed by bhakti poets in other linguistic devotional traditions.

As Girish Karnad said, Kannada sensibility returns to the enthusiasm of the Vachanakara age just as the tongue returns to the aching tooth. In the process, one can also listen to the authentic voices of women poets who saw the turbulent society of their times from a woman-centric perspective.