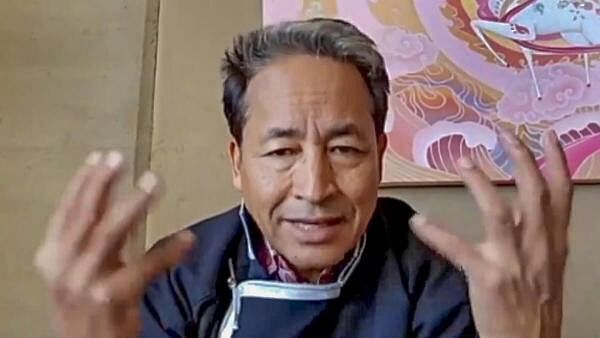

Education reformist Sonam Wangchuk.

Credit: PTI Photo

Innovator and education reformer Sonam Wangchuk is on a mission to ensure that the ecologically-sensitive Ladakh region, known as the Third Pole, is protected under the Sixth Schedule of the Constitution. Through a hunger strike, he has drawn international attention on the impact of indiscriminate exploitation and climate change on the fragile biomes of the Himalayas. With the glacier receding and weather patterns shifting, the protest is as much about safeguarding an ecosystem and its culture as it is about ensuring the survival of more than two billion people who are dependent on the Himalayas, says the Magsaysay awardee, in an interview with DH’s Anitha Pailoor. It is time voters make a green impact on electoral politics visible, he says, as he prepares for the Pashmina March on April 7.

How do you see the rest of India responding to the crisis in the Himalayas?

It was touching and moving to see that the nation, as I hoped and expected, responding (to the crisis). They did not see Ladakh or the Himalayas as this far-off place that does not bother or affect them. They see it as a part of the bigger system that the nation depends on, and for its (Himalayas) own sake. I think this is how it should be.

Unless we as a nation make our wishes clear, politicians will always be swayed by immediate, instant gains over long-term losses, and long-term gains if they do things well. The strength of democracy is that people can participate and influence people in power. The weakness is that the leaders we elect think of five years and not beyond that. If people have that farsightedness and base their vote on visionary leadership, then leaders will be forced to honour the aspirations and expectations of the people. And that is what I see happening, at least at the beginning stage.

I appreciate the student solidarity with us in the mountains. Now, I am urging them to look around and showcase what is happening in their own areas — forests are being cut off for small gains meant for a few people. All such things we should bring to light. A green impact on electoral politics should be visible. Even if we do not have a green party, the colour should be speaking through the mood of the nation.

By not bringing Ladakh under the Sixth Schedule of the Constitution, people have inferred that the government intends to bring in industries. What changes with regard to corporate developments have you already started noticing?

We have not yet started noticing only because our fate is not decided. All these industrial lobbies are sitting on the fence, the Himalayan fence, to see whether it will be protected, in which case, they will withdraw. Or if the fence is left open, they will pounce. We have only seen the introduction of the least harmful ones like solar energy parks. These parks are huge. Although these are good for the nation, they should be done in consultation with the local people who live with the consequences. That is exactly what the Sixth Schedule (of the Constitution) gives and without that, our land will be taken away without even an explanation. Why only pastureland and not some waste land? So all that will come if there is some restriction on what we call growth. For Ladakh, there is already this provision of the Sixth Schedule. We should definitely get that. In other parts of the Himalayas too, there should be new mechanisms of safeguarding for tomorrow.

The Sixth Schedule was designed to safeguard both nature and culture. Of course, each of these industries, when they come, will bring hundreds of thousands of people and these will be people who are not used to living in a different geography. So, we cannot have huge influxes of people who do not know the art of living in such terrains. That will be the destruction of this culture that has evolved over thousands of years, which respects nature, which respects simplicity. Suddenly, if you replace it, it will be a disaster for everyone — for those who come and for those who live here.

How do people's lifestyles, both near and far, impact the fragile ecosystems of the Himalayas?

There are various levels of that. First one that everyone now has heard of is global warming and climate change. However, that is a bit too removed from people’s own lives. Somebody in Beijing or Paris will not be able to see how their lifestyles affects glaciers in the Andes or the Himalayas. Here, people are aware but are not moved into doing anything. We should ensure they are sensitised to act — from children in schools to grown-ups in their jobs, to live lightly and sensibly on this planet.

Secondly, new research shows that local lifestyles are also harmful. For example, the lifestyles of people, the burning of the stubble, industrial smoke and vehicular traffic in the foothills of the Himalayas — from Chandigarh to Delhi; from NCR to the Gangetic plains — are rendering the glaciers ‘black’ (due to carbon deposits) in the high Himalayas. This accelerates the melting of glaciers. As you go higher into the hills, whether it is Dehradun, Kashmir or Shimla, these effects worsen. Even in Ladakh, heavy tourism, unbridled diesel cars, etc. carry smoke to the glaciers. It is a national issue.

What is your take on the employment/livelihoods vs environment debate? Do you see the need for a new development paradigm?

The whole world should redefine development and what they call growth. Because it should not be at the cost of your tomorrow. Today’s growth at the cost of tomorrow is the stupidest thing we could do. After having evolved so much, in science, technology and spirituality, if we do such things in the name of development, it will be as though we cut through a branch that we were sitting on.

We are making a joke of ourselves if we just look at jobs and employment. These are expectations and aspirations from the 19th and 20th centuries. Realities are very different. That’s when we were ignorant. We did not know there were limits to growth and development. Now we know better. So, we better learn to live simpler lives and enjoy the depth of life rather than the peak.

Why did you choose to fast as a way of protest? Do you think protests have the intended impact in current times?

We chose fast because that is the best we can do. We can inflict pain on ourselves, we do not want to inflict it on others. We wanted to do it differently and in the way that Mahatma Gandhi did for India. Sooner rather than later it will have an impact. It may not have an immediate outcome. Sometimes governments are stubborn but as people’s engagement grows, they will be forced into shape or they will be put out of power if people become aware and empowered.

What is your view on India's stance on climate justice for the global south?

India should seek (climate justice), but I do not like the argument that you have already polluted, it is our turn to pollute. We have to show better ways, we should not follow the example of the West and do as bad as they did. We should make them realise that their rise was destructive but India’s rise is peaceful and positive.

How is climate action linked with gender and social justice?

Ladakh doesn’t have too many gender issues. It is quite an equal society. But I do see new, undesirable ways getting adopted. For example, even if society and life are equal, politics and political leadership are male-dominated and that is very sad.

In the past, you have discussed how other creatures of nature need representation as well in a democracy. Why do you see the need for this?

Everything we do is so human-centred. We think of only the growth of human beings, we do not see the destruction of the rest of our siblings on this planet. As I said earlier, 59% of our wildlife is wiped out. By now some 63% or so. We do not even talk about it. We only talk about 7% and 9% growth. Future generations will laugh at us for calling this ‘development’.

You have shown through your work that solutions to climate change need not be complex. How can this be replicated?

The answer lies in simplicity. And in reducing desires, and increasing happiness and contentment. That is the oldest technology that India can pride itself on and it can teach the world. So you don’t have a bottomless bucket that you try to fill with all your technology, cars and rockets, but rather a bucket with a bottom that fills easily and people are happy. After all, we are not chasing technologies, we are chasing happiness. Education at wider levels has a role to play as well.