In a major challenge to the popular “Aryan Invasion” theory, an Indo-US team of researchers on Friday presented scientific evidence from the Harappan era to argue that such a large-scale migration from central Asia to India never happened.

The research – published in Cell, one of the world’s top journals – not only sets aside the Aryan migration theory but also notes that the hunter-gatherers of Southeast Asia changed into farming communities of their own and were the authors of the Harappan civilisation.

The evidence comes from the analysis of DNA samples extracted from the skeleton of a woman buried in Rakhigarhi four to five millenia ago.

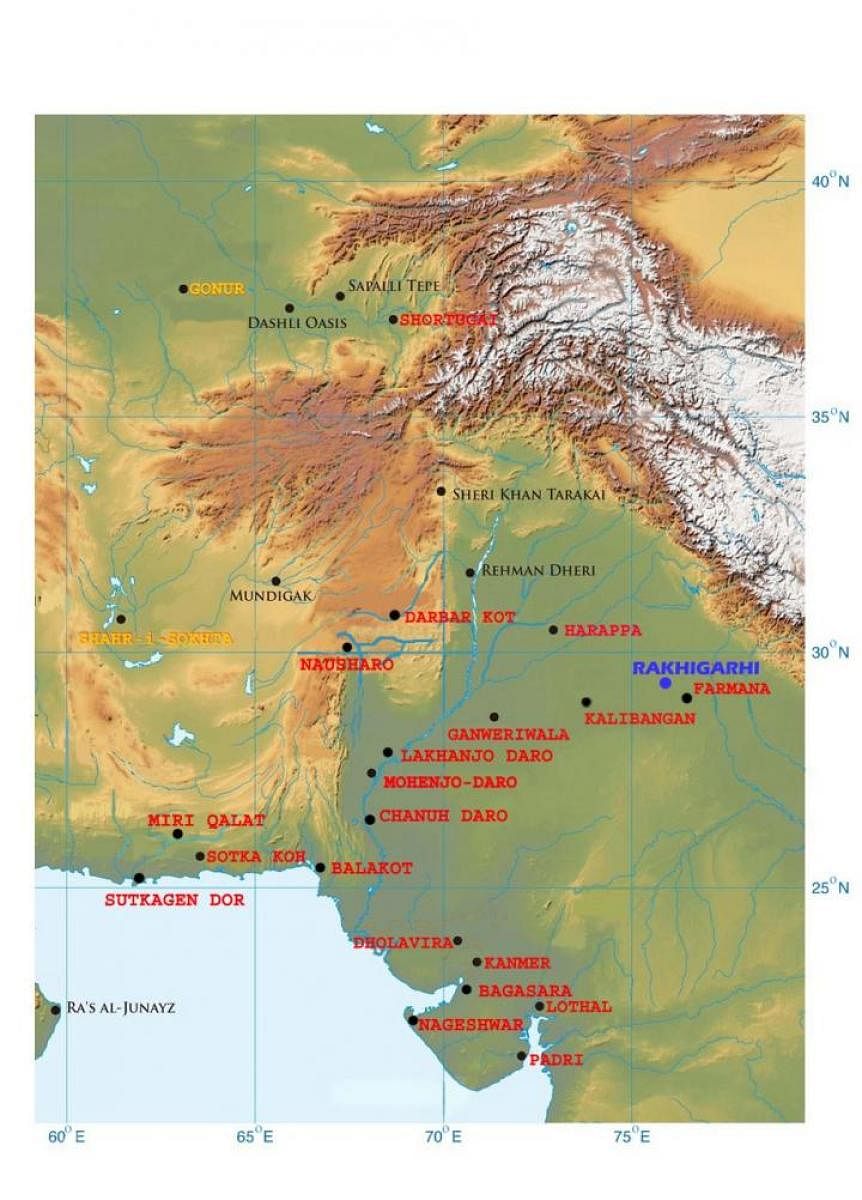

Located near Hisar in Haryana, Rakhigarhi is the largest Indus Valley Civilisation site known so far.

Researchers matched their findings from samples that they collected from 11 other skeletons from around the world and compared them with known scientific data to arrive at a comprehensive picture on a complex migration pattern seen in Asia a few thousand years ago.

“The ancient DNA results completely reject the theory of Steppe pastoral or ancient Iranian farmers as a source of ancestry to the Harappan population. It demolishes the hypothesis about mass human migration during Harappan time from outside south Asia or before,” said V S Shinde, an archaeologist at Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute in Pune and one of the lead authors of the study.

The Rakhigarhi samples do have traces of genes of Iranian lineage. However, the antiquity of such genes is 11,000-12,000 years, way before the Harappan civilisation. Since 7000 BCE, there is no evidence of the South Asian genes being mixed with the central Asian genes.

“Research showed the Vedic culture was developed by indigenous people of South Asia,” Shinde asserted.

The knowledge of agriculture was indigenous as the pre-historic hunter-gatherer learnt how to do farming. “This does not mean that movements of people were unimportant in the introduction of farming economies at a later date,” researchers reported.

Several scholars, however, are not yet ready to bury the Aryan invasion theory for good even though they agree that the study opens up a new avenue for research.

“Rakhigarhi doesn’t really apply to the Aryan period. It’s prior to that,” said an eminent historian not linked to the study, who was not willing to be quoted.

Origin of the Indo-European languages remains the Achilles Heel of the new findings. “Our study debunked the Aryan invasion theory. But language remains an unresolved issue,” Neraj Rai, a scientist at the Birbal Sahani Institute of Paleobotany, Lucknow, and one of the co-authors of the study told DH.

Rai said the research also pointed towards an “Out of India” theory around 2500-3000 BCE. The evidence comes from a related study by the same set of researchers, published simultaneously in the journal Science on Friday.

The Rakhigarhi woman’s genome matched those of 11 other ancient people who lived in what is now Iran and Turkmenistan at sites known to have exchanged objects with the Indus Valley Civilisation. All 12 had a distinctive mix of ancestry, including a lineage related to Southeast Asian hunter-gatherers and an Iranian-related lineage specific to South Asia.

The Indus Valley Civilisation, which at its height from 2600 to 1900 BCE covered a large swath of northwestern South Asia, was one of the world’s first large-scale urban societies. But there are still many unanswered queries on the ancient Indian civilisation.