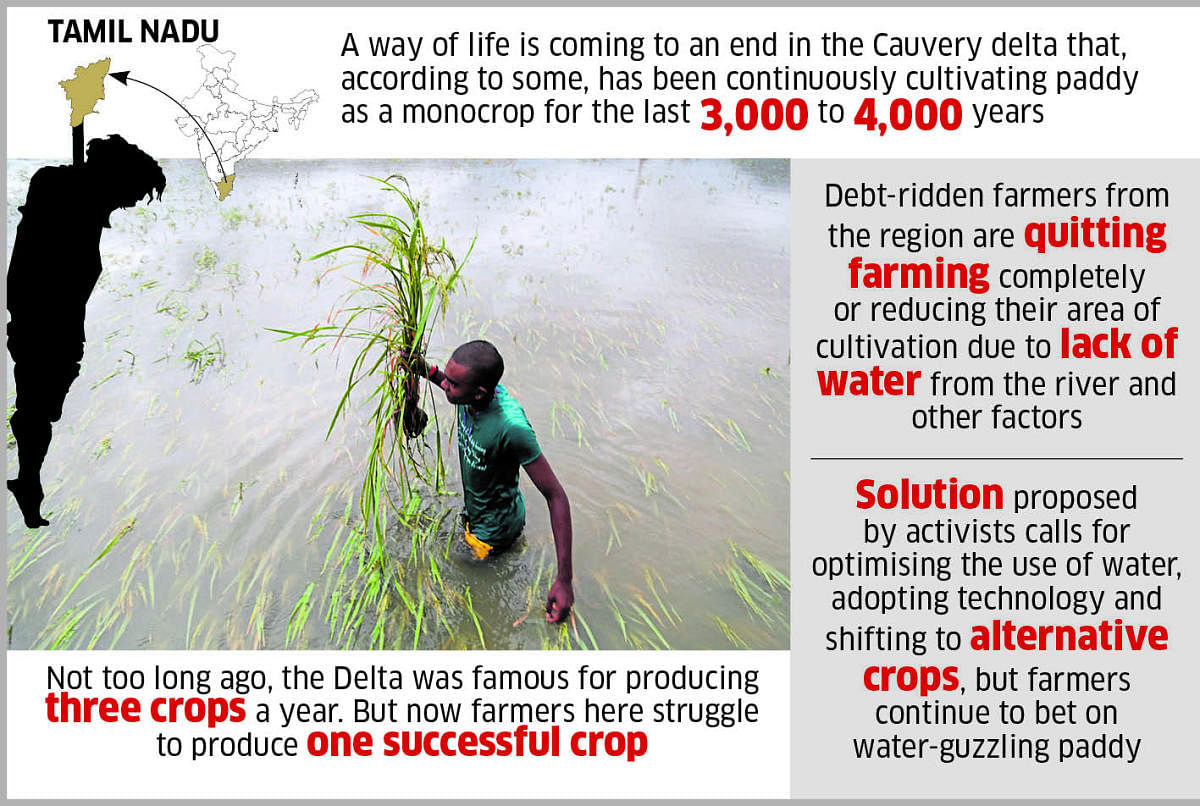

Agriculture has flourished in Tamil Nadu’s Cauvery Delta for thousands of years. But with a large number of farmers from the region now immersed in debts, many quitting farming completely and others reducing their area of cultivation due to lack of water, what is unfolding is not a mere agricultural crisis. A way of life is coming to an end.

The Delta – comprising Thanjavur, Thiruvarur, Nagapattinam and parts of Pudukkottai districts – with its alluvial soil, was famous for producing three crops a year not too long ago. But much of it now struggles with producing one successful crop. The region, covering 11.35 lakh hectares of farmland with rice occupying 61% of the net irrigated area, has a history of continuously cultivating paddy as a monocrop that goes back 3,000 to 4,000 years according to some. But from being a symbol of plenitude and pride, it has now been reduced to a symbol of perennial want.

A combination of factors have led to the situation: the row over sharing of Cauvery waters between Tamil Nadu and Karnataka has meant uncertainty and non-release of waters during drought years, impacting sowing; the plundering of natural resources by Tamil Nadu government that allows rampant sand mining along the Cauvery bed and its tributaries has adversely affected the health of the river; and exploitation of groundwater by farmers through bore wells has meant that water has gone down to between 400 and 500 feet in most parts of the Delta.

However, the basic issue has to do with the lack of availability of water. “First of all, one needs to understand that Cauvery is a deficit river. The total water demand exceeds the total water available in the Cauvery basin and that is the primary reason for the crisis during distress and drought years,” said Mannargudi S Ranganathan, general secretary of the Cauvery Delta Farmers Association.

For farmers who have cultivated their crop here for generations, this explanation makes little sense.

“We keep harvesting paddy every year in the hope that we will get good returns only to end up disappointing ourselves. We make a good yield once in 10 years and that satisfaction of having produced successful crop encourages us to do farming for the remaining nine years. That’s how difficult or tragic a farmer’s life is,” said R Vedamurthy, who cultivates paddy in his 15-acre field in Killukudi village in Nagapattinam district.

Many in the Delta now also hold the view that only those with “back-up money or resources” can sustain for long in agriculture in the current scenario. “If we depend only on our farms to sustain in this field, we will find ourselves immersed in deep debt. Only with some outside backing, we can continue in this field,” said Indira Mohan, a farmer in Paravakottai, Thiruvarur district. But farmers too are to be blamed to an extent for refusing to come out of water-guzzling paddy and experiment with alternative crops.

Ranganathan, the first to take the Cauvery water sharing issue to the Supreme Court, held that by optimising the use of water, adopting technology and shifting to alternative crops, farmers could regain their past glory.

However, farmers continue to swear by paddy.

They blame the “non-profitable” Minimum Support Price mechanism, non-availability of labour and rising input costs for the crisis. “Only when we get the right price for our produce will we be able to make profits. Else we will only be practising agriculture because we don’t know any other profession,” said ‘Cauvery’ S Dhanapalan, general secretary of Cauvery Farmers Protection Association.