It’s a debate that never dies. Reservation, long considered a political hot potato, continues to bring people out on the streets demanding adequate “representation” and more “inclusivity”. Irrespective of the judicial contours of the topic, political parties fashion their quota policies to appease vote banks as they gingerly reassemble caste cards in election years.

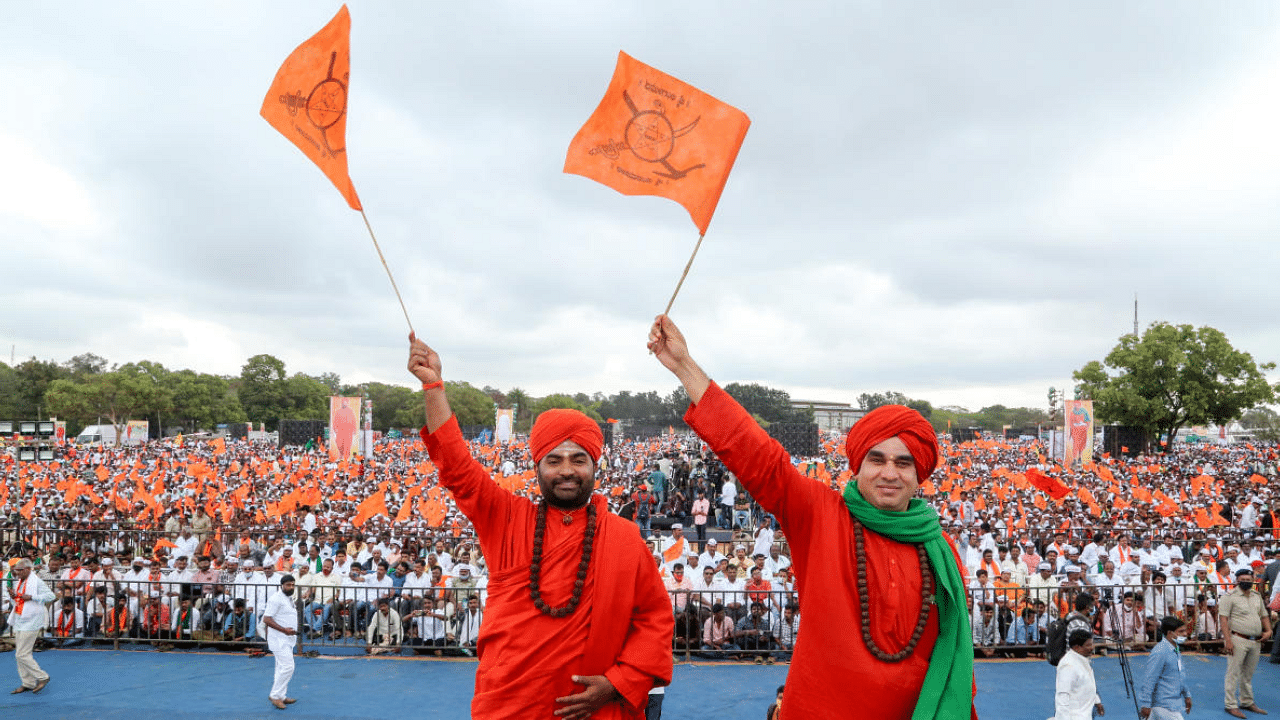

In the recent past, several groups including the Patidars in Gujarat and Jats across North India, violently agitated for inclusion in the OBC (Other Backward Class) category. More recently in Bengaluru, thousands from across Karnataka belonging to the Panchamasali sect within Lingayats rose in protest, demanding separate reservation.

At the same time, the Supreme Court stayed the Maratha reservation in Maharashtra, as it exceeded the 50% limit set in the Indira Sawhney judgement. The court referred the matter to a five-judge bench since a substantial question of law on the powers of the state government to determine socially and educationally backward communities were involved. Accordingly, the larger bench directed all states to submit their responses.

So, who is a “backward class citizen”? The question remains unanswered even decades after Dr B R Ambedkar elaborated on the topic in the Constituent Assembly.

Different communities continue to claim to be backward to corner reservation benefits, and if at all considered, are not satisfied with the quantum of benefits. And regardless of the constitutional underpinnings of the policy, political parties continue to churn out caste-based opinions and extract mileage.

Article 14 of the Constitution commands the State to not deny any person equality before the law and ensure there is equal protection of the law, thereby enunciating the principle of: Equals should be treated equally and unequals unequally.

Similarly, Article 16 was added to ensure equality of opportunities in employment. It also gave power to the State to provide reservation benefits to backward classes who are not adequately represented in State services.

The introduction of Article 16 brought about questions in the Constituent Assembly as to who constitute “backward class citizens”. What was the need for such a special provision, and if at all required, what should be the quantum of such benefits? Ambedkar, in response, stated that it was agreed in principle that there should be “equality of opportunity, without any hindrance”; it is also equally important that there should be a “provision made for entry of certain communities, which have been outside the administration — due to historical reasons — which has been controlled by one community or a few communities”. In the absence of such a provision, the principle of “equality of opportunity is destroyed”.

Ambedkar said, “A backward community is a community which is backward in the opinion of the government.”

For more specific answers, we can refer to Article 340 which empowers the President to appoint a commission to investigate the conditions of backward classes, especially socially and educationally backward classes. Furthermore, with respect to the quantum of reservation, there was no specific percentage laid down, but benefits “must be confined to a minority of seats”.

The concerns raised in the Constituent Assembly seemed to have been settled at that point in time, but for generations to come, those confusions remained.

The Indra Sawhney case

The Supreme Court came to the rescue in the Indra Sawhney case (1993) while upholding the recommendations of the Mandal Commission. The court held that caste can be a base to determine backwardness. But it rejected economic criteria alone as a base for backwardness. The court also set a limit of 50% reservation benefits, but in extreme situations, it can be relaxed.

While thus stood the law, in 2019, the Modi government, in deviation from this judgement, introduced Articles 15(6) and 16(6) to the Constitution, creating an ‘Economically Weaker Sections' (EWSs) category, enabling the State to provide the benefits of 10% reservation based on economic criteria alone. However, the objective behind introducing such a provision seems to be to corner the votes of forwarding communities, which became evident in Karnataka when several Brahmin community members approached Chief Minister Yediyurappa for EWS benefits.

Similarly, dominant caste groups like the Patidars, Gujjars, Jats and Marathas, who, irrespective of being majority land-holding communities, continue to demand reservation due to a perception that economic power is increasingly shifting from rural areas to big corporations.

Political parties capitalise on such apprehensions. For instance, the Devendra Fadnavis government used Maratha reservation in excess of a 50% limit to gain the trust of the community. The Jat community has also been victims of vote bank politics under the UPA as well as NDA governments. The UPA tried to please them by including them in the OBC list, while the National Commission for Backward Class had in fact declared them as not socially backward. The decision came to be struck down by the Supreme court in 2015.

Closer home in Karnataka, Yediyurappa has constituted a three-member high-powered committee to look into the demands of the Panchamasali community, as well as that of Kurubas and Valmikis, while the fact remains that some of them are already enjoying the benefits of reservation.

Voice of dissatisfaction

The demand for reservation, regardless of how effective it may be in the context of shrinking jobs in the state sector, has become the voice of dissatisfaction with the options available to youth.

Vote bank politics that polarises communities defeats the purpose of inclusive policy. The introduction of reservation as a constitutional provision was to ensure that caste identity withers away by guaranteeing representation of competent members from marginalised communities in State administration. However, over a period of time, the reservation has become part of the grammar of Indian politics and has deviated from the objective of redressing historic discrimination to becoming a way to garner votes. This has led to the entrenching of caste divisions, without redressing real inequality.

Moreover, the emergence of the private sector, where reservation policy does not apply, has led to a downsising of government departments, cutting down the prospects of public employment.

While resources continue to be monopolised and inequality is rampant in administration, the need to increase the 50% cap or expand the benefits to others will only make the caste identity stronger and the hostility bitter.

The tragedy of course is that reservation has not been implemented effectively, yet it remains the calling card of not only those who were discriminated against but of even those communities which were relatively better off.

The government has failed to address the unequal distribution of existing reservation among castes. The demand for ‘internal reservation’ with groups like the Madigas in Andhra Pradesh, Telangana and Karnataka indicate the failure of the reservation to cater equally to all sections.

The only solution put forward by courts has been to limit the policy by excluding the “creamy layer” — a socially and economically advanced group among the backward class.

There is a need to expand employment avenues, provide better education facilities for students among Dalit communities and ensure that the State plays a proactive role so that reservation reaches all those who have been denied its benefits. But that’s a long way to go, considering the present state of affairs.

(The author is an advocate with the Alternative Law Forum, Bengaluru)