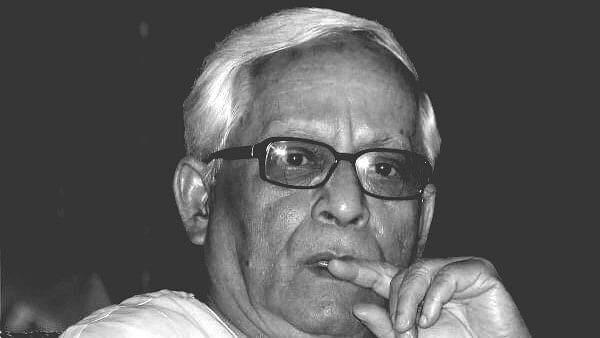

Former West Bengal chief minister Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee.

Credit: PTI Photo

New Delhi: Former West Bengal Chief Minister Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee, a Marxist veteran and one of the last few dhoti-clad quintessential Bhadralok politicians, died in Kolkata on Thursday. He was 80 and is survived by his wife and son.

Bhattacharjee, who was the Bengal chief minister for 11 years between November 2000 and May 2011, was unwell for quite some time because of his persistent lung problems, thanks to years of chain-smoking.

Last year he was put on life support after he contracted pneumonia but was discharged from hospital after 12 days.

The young generation will remember him as someone who had a dream of bringing back the industry in the eastern state but stumbled on the land acquisition process, a flaw that was encashed by then opposition leader Mamata Banerjee to defeat him in 2011 riding high on the success of the Singur and Nandigram movements.

In the Jyoti Basu cabinet since 1977, Bhattacharjee first became a Deputy Chief Minister for two years between 1999 and 2000 before he replaced an ailing Jyoti Babu and successfully led the Left front in two elections in 2001 (199 seats) and emphatically in 2006 when the communists won 235 out of 294 seats in the assembly.

The suave and smiling Bhattacharjee wanted to change West Bengal’s notorious anti-industry image as he realised stopping the flight of the capital is the only way to grow as agriculture alone would not be sufficient to meet people’s aspirations.

Capitalising on 'Brand Buddha', he pushed hard to woo the industry to promote industrialisation to breathe new life into Bengal's moribund economy. His strong public criticism of CITU’s (CPM trade union) militant tactics to drive away the industry earned him massive public support.

But he underestimated the damaging potential of the agitation by a motley group of farmers, who objected to the forceful land acquisition at Singur for Tata’s small car factory. “We are 235, they are 35. What can they do,” he famously said, describing the protests at Singur and at Nandigram (for a SEZ) as blips to his industrialisation roadmap. The rest, as they say, is history.

One of the young Turks of the CPM picked up by the communist stalwart Pramod Das Gupta in the 1960s, Bhattacharjee came from a literary family. He was a distant nephew of the renowned Bengali poet Sukanta Bhattacharya, who played a significant role in modern Bengali poetry.

Outside politics, he was well known in the world of literature and culture, having translated Gabriela Garcia Marquez and Mayakovsky in Bengali and penning other literary works besides realising Nandan, a state government owned film and cultural centre in Kolkata.

With his strong ideological moorings, habit of quoting Rabindranath Tagore, and love for cricket, cinema, literature and afternoon siesta, he was one of the last few intellectual politicians, who are a dying breed nowadays.

It was not a surprise when in true communist tradition he refused to accept the Padma Vibhushan, offered by the Narendra Modi government, in 2022.

But ironically despite all the positives, the incorruptible Bhattacharjee will always be associated with the fall of three decades of communist rule in Bengal even though he read the writings on the wall in advance and tried to change the narrative.