The history of our wondrous land is embroidered with unlikely events which really happened. The tale of the Adil Shahis of Karnataka is one of them. It started long, long ago, and very far away.

In the thriving slave markets of Persia, in the distant 15th century, a man named Yusuf was sold to Mahmud Gawan of Bidar. Clearly, he had a natural talent for intrigue and realpolitik. In 1489, he became the first Adil Shahi king of Bijapur (now Vijayapura). More than five centuries later, we drove into this historic town.

Architectural masterpieces

Atop the Serzi Buruj, the Lion Tower, a great canon sat protecting the rich fields and farms below. The composition of its dark-green metal is still a secret. It is rustless, flawless, has a brilliant sheen, and remains cool to the touch even on the hottest days. And when we tapped it with our knuckles, it rang like a gong. Malik-e-Maidan is a great work of art besides being a weapon of mass destruction of the 16th century.

Another masterpiece of Adil Shahi creativity is Ibrahim Adil Shah II’s own mausoleum: the strikingly elegant Ibrahim Roza. Ibrahim’s tomb and a mosque stand facing each other on a high platform accessed through a gate-tower with four minarets. The gazetteer says,

…the front (of the mosque) is further ornamented by hanging stone chains, each carved out of one stone ending in thin carved and elliptical stones.

In the great mosques in Turkey, we have seen similar decorations. We were told that the chains held ostrich eggs because they kept away spiders and their dusty cobwebs.

The most beautiful and abstract murals in Vijayapura also belong to the creative times of Ibrahim II. We got permission from the parish priest to visit the little All Saints Church. Pendants, chains, roundels, medallions and panels glow in brilliant colours from the ceiling and walls of this exquisite church. This Christian place of worship has, very carefully, protected these essentially Islamic art forms when other murals of the Adil Shahi period have been destroyed. This is very reassuring because it shows the faith-bridging sensitivity that has cemented our multi-religious land.

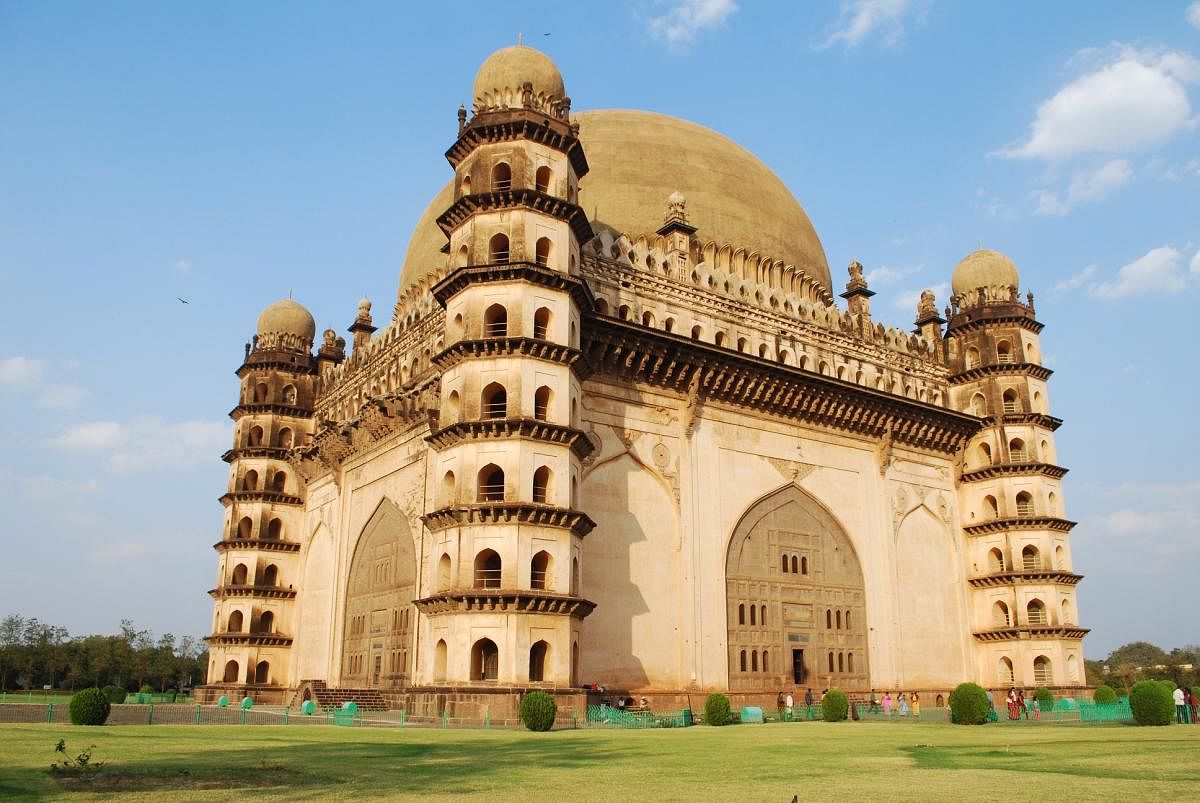

The big dome

Then, on a cool, clear morning, we drove to Vijayapura’s most famous monument: the dominating Gol Gumbaz, the mausoleum of Mohammed Adil Shah. The sheer massiveness of the tomb hit us. It’s enormous. It sits squat and powerful on a flat slab of rock and is a vast cube enclosing a great hall, capped by an unsupported dome. In fact, it is too symmetrical to be appealing. It gave us the overwhelming impression of a formidable defensive structure rather than one designed to hold a tomb.

We trudged up the stone staircase built into one of the towers and then stepped out onto the gallery that encircles the base of the dome. Here, the softest whisper made into the wall curving around the gallery will be heard emerging from the wall at the other end.

Mohammed died in 1636 and was entombed in the Gol Gumbaz. His 18-year-old son, Ali Adil Shah II, succeeded him. He probably realised that the unbending Mughal, Aurangzeb, would do his best to destroy Vijayapura. Uncertain of his future because of the Mughal threat, he started building his own mausoleum virtually as soon as he became the king. He wanted it to be larger and grander than his father’s Gol Gumbaz.

On the evening of our last day in Vijayapura, we visited the unfinished tomb of Ali Adil Shah II, Bara Kaman. From a high plinth, a forest of stone arches emerged, still remarkably intact after three-and-a-half centuries of exposure to the weather. It is roofless and has always been so. People wandered in the striated shadows cast by the pillars, two crows preened their feathers on the false tomb of Ali Adil Shah II, built above his real grave, deep inside the high platform.

It wasn’t the feared Mughals who had killed Ali Adil Shah II. He had managed, by guile and grace, to buy peace, and spent the last years of his reign enjoying the good things of life. He died of paralysis in 1627 and was succeeded by his four-year-old son: the last of the Adil Shahis.

The dynasty had survived for 200 years. It had faced internal and external challenges, changed its borders with the ebb and flow of history, built a vast array of monuments of which we had seen only the most important, had had considerable achievements in arts and architecture to its credit. But, on September 3, 1686, Sikandar Adil Shah surrendered the keys of his citadel to Emperor Aurangzeb, and Vijayapura became a province of the Mughal empire. This was a precursor of events that would overtake the whole of India a little less than two centuries later.