Credit: DH Illustration/Deepak Harichandan

By Andreea Papuc

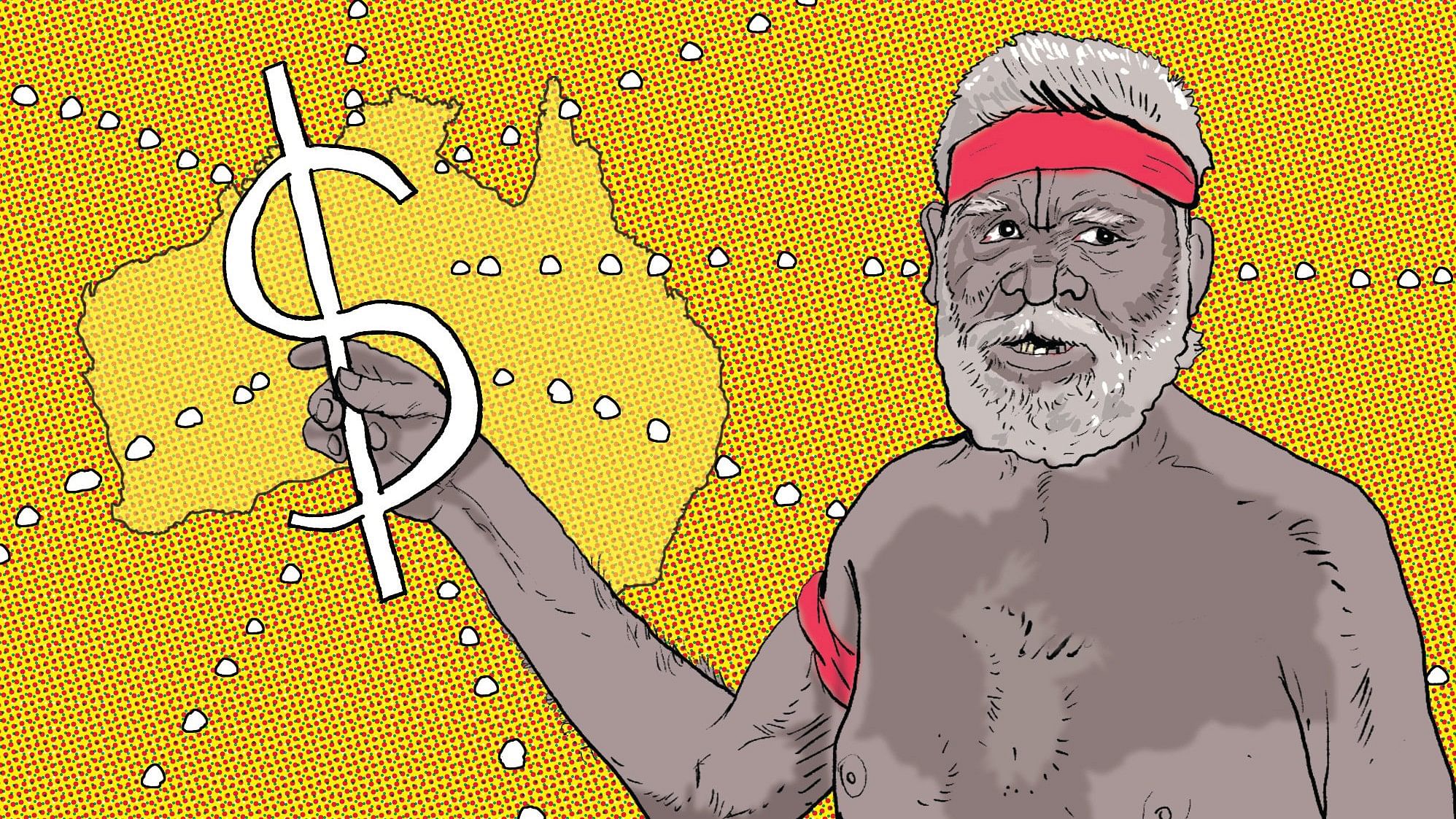

Ten months after a stinging rejection to recognise Indigenous Australians in the constitution, the wounds still run deep. So does the desire to move forward.

Traditional owners of the land want action. That was the message to the country’s premier Indigenous gathering involving 2,000-plus First Nations leaders, politicians, academics and business people who met this month on an escarpment overlooking the Gulf of Carpentaria in northeast Arnhem Land, a remote part of the Northern Territory. The theme of the 2024 Garma Festival was “Fire. Strength. Renewal.”

It’s not easy. The challenge for Australia’s Indigenous communities that dot a harsh, sprawling landmass is how to mesh 60,000 years of cultural traditions that guide everyday life with today’s economic realities. How do you move some of the world’s most disadvantaged and secluded communities off welfare to become economically empowered? How do you take their unique knowledge and develop policies based on mainstream economics?

Bipartisan government support is lacking as politicians bicker, while the conservative opposition coalition needs to find a way to re-engage with Indigenous Australians. Plus, negotiating with a complex web of clan structures rooted in tens of thousands of years of history is delicate and requires sensitivity. But you have to begin somewhere. “These two cultures need to come together. Make a fresh start where everyone walks together,” said Tobias Nganbe, a Murrinhpatha traditional owner.

Yet how the traditional owners of the land in this largely untouched corner of Australia — there are about 16,000 people in Arnhem Land, an area roughly the size of South Korea — are running businesses while preserving their culture offers some hope.

You can’t miss the name Gumatj Corporation. The 100% Indigenous-owned business was set up to foster sustainable economic and social growth for the Yolngu people. Its board includes senior members of the prominent Yunupingu family of the Gumatj clan. Its interests span timber, construction, real estate, and mining (Gulkula Mining is the first Indigenous-owned and operated mine in the country).

There is much angst in the local community about dwindling employment. Rio Tinto Group is decommissioning the bauxite plant that has been the lifeblood of this area since the 1960s, and will be gone in about three years. Australia’s wealth is underground and royalties have sustained the region — the main town, Nhulunbuy, was established as mining took off.

Klaus Helms, Gumatj Corporation’s chief executive officer who has lived on the Gove Peninsula for almost seven decades, has the task to chart a course for when the mining royalties dry up. He is confident the area can reach economic independence. “We are small, but we take the risks and say ‘let’s try,’” he said during a panel discussion with

Rio Tinto’s chief executive for Australia, Kellie Parker.

Helms sees opportunities in agriculture, developing the deepwater port, seafood production, timber harvesting and cattle, among others. Gumatj Corporation was involved in the establishment of the Arnhem Space Centre, one of Australia’s first commercial space launch facilities.

I later bump into Helms in the Garma festival grounds, where reddish pellets of bauxite crunched beneath our feet. “To have real independence you cannot rely on welfare,” he says, though some government support is needed. There is also a role for the nation’s corporates, because they can open the doors to negotiate with the politicians in Canberra.

With the referendum in the rear-view mirror, this is the time for Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s government to turn its focus on stimulating economic development to lift the living standards for Indigenous Australians. It has a massive role to play in providing infrastructure, health and education in impoverished and disempowered remote regions.

Very few Australians have or will ever visit this part of the country. Arnhem Land’s vastness is bewildering: almost 100,000 square kilometres (37,000 square miles) of sparsely populated land owned by Indigenous communities under native title acts. You need a permit to enter. It’s roughly a 12-hour plane trip from Sydney via Darwin, about as long as it would take to fly to Dubai. To drive from Darwin — Northern Territory’s

capital — would take equally as long via mostly unsealed roads. Flying out of the local Gove Airport at night, you don’t see a single light below.

To understand its significance, you need to look at how the history of a region that is closer to Indonesia and Asia than to Sydney or Melbourne, helped hone an entrepreneurial bent, and became the birthplace of the land-rights movement.

Way before British colonisation in 1788, its Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples traded with the Macassans of Sulawesi, who sought the highly prized sea cucumbers (trepang) found in the coastal waters, which they exchanged for goods such as cloth, tobacco and metal. This trade changed the life of the Yolngu, and the cultural connections continue to be celebrated in local dances and language (White people are called balanda, an alteration of Hollander, which refers to a Dutchman).

The trepang trade dwindled by the end of the 19th century. Then came the Methodist missions that were established from the early 1920s to 1970, built with Yolngu labour. During World War II, the Allies set up air force bases across the Arnhem region; Yolngu provided services during the war in a specially created reconnaissance unit to monitor the coast for Japanese intrusions.

For now, investment from the top end of town is unlikely to flood into remote Indigenous communities. Returns would be extremely difficult outside of mining. But there are other avenues that

could empower First Peoples and improve their wellbeing.

Already disproportionately exposed to a range of extreme weather, Indigenous Australians could play a greater role in combating climate change. There are 39 Indigenous owned and operated carbon farming projects across the country, according to the Indigenous Carbon Industry Network. Not only do these businesses provide economic empowerment, employment and training in isolated regions where jobs are scarce, but they also draw on Indigenous expertise, such as fire management, while applying a Western market system.

The development of nature and ecosystem service markets have significant potential, notes Kobad Bhavnagri, global head of strategy at BloombergNEF, who was also at Garma this year. It “will then help to plug a hole in our social system — our failure to value the knowledge and labour of indigenous peoples who have responsibly managed natural assets for thousands of years.”

The majority of Australians live along the east coast. But Sydney and Melbourne are not the only Australia. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders in faraway areas might make up a fraction of the population; however, their contributions, traditions and knowledge have been underestimated and dismissed for far too long. If there was one message out of Garma it was that it’s time they have a seat at the table.

Stephina Salee, a proud Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander from the Kaantju tribe in Cape York, Argun clan in Badu Island and Tharbu clan in Saibai Island, is the CEO of the Dhimurru Aboriginal Corporation, whose rangers manage 550,000 hectares of land and sea on behalf of the Yolngu. She perhaps summed it up best: “We’ve been engaged for

too long. Now we want to get married. It’s not about collaboration anymore, it’s about coexistence.”

Like any marriage, this is involves compromise and a genuine desire to forge a long-lasting and successful partnership based on mutual respect and trust.