The International Institute of Population Sciences (IIPS) is a prestigious deemed Indian university and a pioneering 67-year-old institution known for, among other works, its highly regarded and oft-quoted National Family Health Survey (NFHS) series and attendant reports. The reports analyse mounds of data under NFHS rounds that for the last three decades have provided an independent grassroots view of India’s demographic and health-related information to tell us if the policy directions are translating to change on the ground. The IIPS thus works in a significant space on crucial data that can hold a mirror to the executive and help drive policy actions in the right direction.

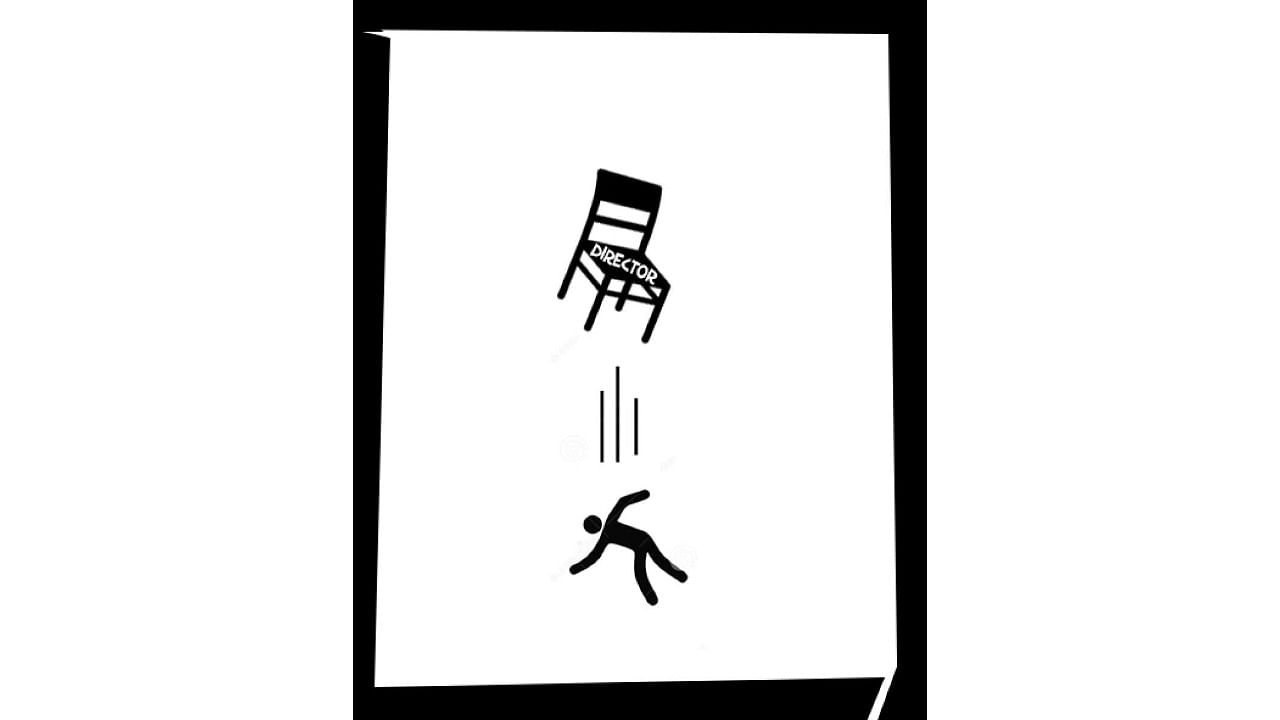

Last week, the director of this valued institution, Professor K S James, a noted demographer, researcher, and former Jawaharlal Nehru University faculty member, was suspended and asked not to leave his headquarters region, which is Mumbai city, pending an inquiry. IIPS faculty and alumni are said to be in shock. The Opposition has criticised the move. Scientists and other faculty members are alarmed. Not much is known about what triggered the suspension, but those in the know say that the suspension order follows other attempts to oust the director. He was apparently asked to resign some months ago. James reportedly refused, saying he had done nothing wrong and wouldn’t leave for no reason.

The suspension would once again raise fears of a high-handed administration ready to go to any lengths to control institutions and punish those who cannot be reined in. It is true that this is a suspension pending an inquiry, not a punishment already. It is true that the government has a right to investigate on the basis of complaints or information it may have received. But if insider reports are to be believed, it is equally true that the government wanted the director out. If it is a matter of irregularities, then how and why would the director be asked to leave and an inquiry be launched only when he refused to go quietly?

The questions take on a larger significance when one looks at the work of the IIPS and its role in putting out data relating to demographics and (under the NFHS series) key parameters like reproductive and child health, socio-economic indicators, fertility, maternal and child mortality, under-five mortality rate, nutritional status, immunisation reach, water, sanitation, gender violence, and even the spread of modern-day lifestyle diseases like diabetes and blood pressure.

It is the latest release of this NFHS report that has told the nation that 19% of Indian households defecate in the open (NFHS-5, for 2019-2021), an improvement from 39% who were reported practising open defecation in NFHS-4, for 2015-16. For rural India, NFHS-5 said 26% of households still had no access to toilets and so practised open defecation. This is an improvement in numbers over the years, but still (if you like to look at it that way), it punctures the Prime Minister’s sweeping claim that rural India is open defecation-free already, made by Narendra Modi himself in 2019 as part of ongoing programmes to celebrate the 150th birth anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi.

The contradiction between the political claims and the on-ground numbers reinforces the significance of a strong IIPS running an independent NFHS and reporting the numbers freely rather than varnished numbers for the authorities to look at and be pleased with themselves. Though the IIPS is a part of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW), it is an autonomous institution and has never faced questions about its surveys and findings. In fact, the NHFS is a survey that has global standing and works with global partners like the ICF of the US, the United States Agency for International Development, Britain’s Department for International Development, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, UNICEF, UNFPA, and the Indian health ministry.

NFHS-5 (2019–2021) has other statistics that tell us that India is not really doing well. Anaemia, for example, has risen. As many as 67% of children aged six months to five years during NHFS-5 had anaemia (haemoglobin levels below 11.0 g/dl), which is higher than the NFHS-4 estimate of 59%. Anaemia in children leads to slower growth and impacts neurodevelopment.

NHFS-5 reported that 36% of children under age five are stunted (too short for their age), which is only marginally different from the 38% seen in NFHS-4, which is chronic undernutrition. Similarly, 19% of children under age five are wasted (too thin for their height), only slightly down from 21% seen in NHFS-4, a sign of acute undernutrition. And 32% of children are underweight, down from 36% during NHFS-4.

These numbers, in one way, point to challenges before a government that is in a rush to claim success and talk victory in all the battles, schemes, and missions it seeks to highlight. The true story is a little different. There is nothing wrong with accepting the truth, fine-tuning policy, and prioritising spending to reach the desired targets. Empty claims will ring hollow and show the government in a poor light sooner rather than later.

The government cannot build a narrative of an India that is a global giant and has a robust economy with children who are anaemic, wasted, stunted, and undernourished. India cannot be claimed to be cleaner if there are announcements that open defecation persists. Instead, the government can rightfully claim full marks for trying. Even if efforts take longer, that will be a journey well-run. It is good to recall that the rush to announce ‘Mission Accomplished’, with well-set optics aboard a US-Navy aircraft carrier after the Iraq war brought nothing but disaster for the USA under President George Bush. We don’t have to go there. And keeping us honest will be independent reports of the kind the IIPS produces. Disturbing such work by suspending the director may therefore not be the best way to proceed with an agenda of development for the people of India.

(The writer is a journalist and faculty member at SPJIMR. Views are personal) (Through The Billion Press)