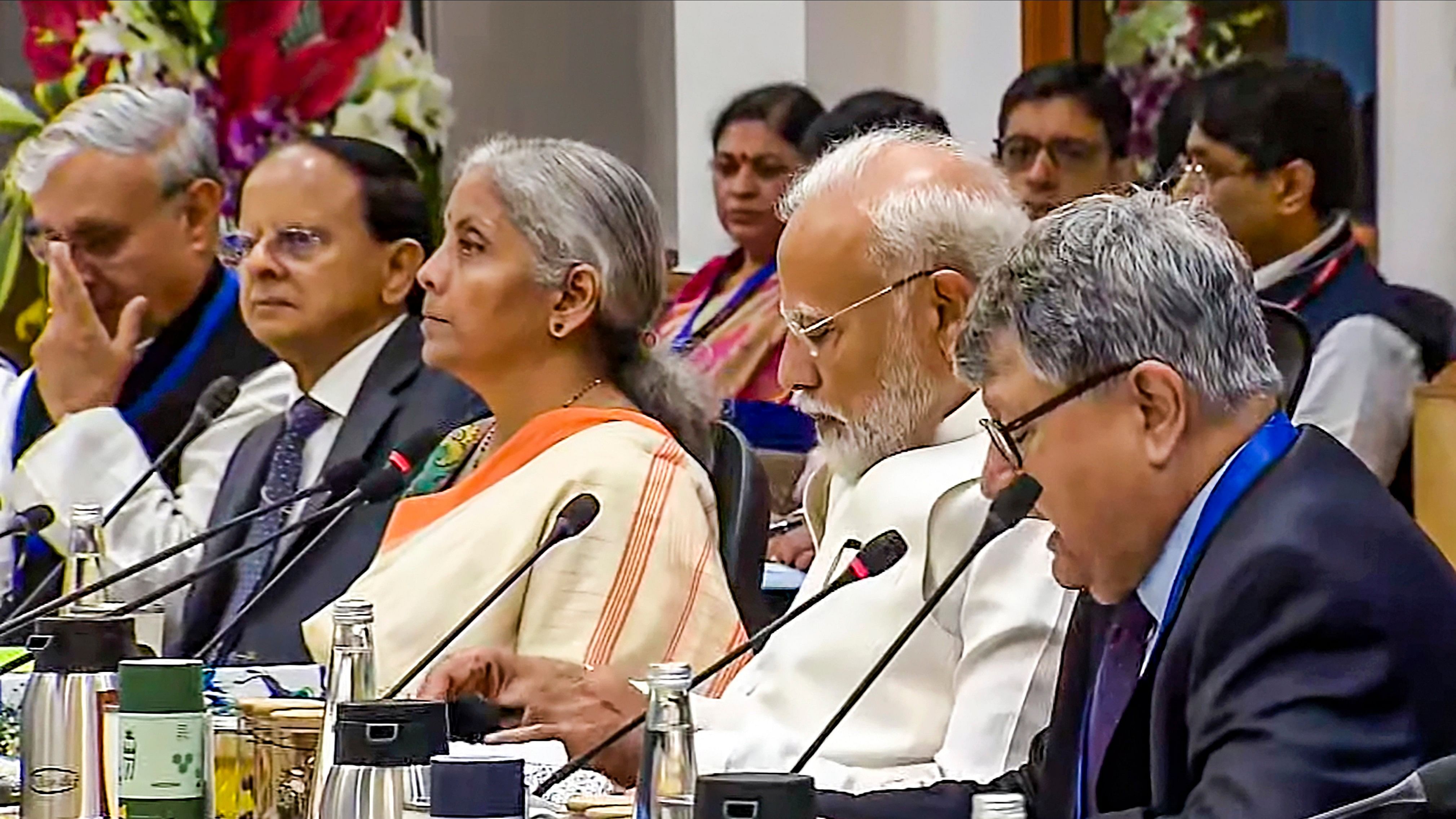

Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman.

Credit: PTI photo

Modi 3.0 will present a full Union Budget on July 23. While there may be some slight tinkering done with fiscal allocations in certain overheads, the macro-fiscal strategy may continue to remain growth-focused.

It is expected the government will continue its higher capex-fuelled spending strategy, even though private investment levels haven’t risen over the last few years, done y-o-y at the substitutive cost of revenue expenditure needs.

On issues, this Budget needs to be three-pronged.

Keeping the noise low, the fiscal math needs to be simple on deficit-and-borrowing considerations, while the core fiscal policy compass can be in the direction of addressing higher (food) inflation woes and creating better employment opportunities.

Inflation may be a key theme to focus upon in this Budget, given how high food price inflation continuously remains a thorn in the flesh of the Government of India, and was also a key factor in the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) losing its critical vote share among middle classes, low-income groups and poor, in some key states like Uttar Pradesh, and Rajasthan.

Food inflation is also the primary driver of inflation in India. India’s Consumer Price Index (CPI) in May 2024 rose to 4.75 per cent compared to 4.31 per cent in May 2023. Meanwhile, the Consumer Food Price Index (CFPI) for May 2024 was 8.69 per cent, compared to just 2.96 per cent in May 2023. This was primarily driven by increasing vegetable prices such as those of tomatoes, onions, and potatoes, which was a result of extreme weather including both heatwaves and floods.

In the core constitutive weight of the CPI, food and beverages occupy 45.86 per cent of the overall weight (including prices of vegetables, cereals, pulses, and milk); miscellaneous holds 28.31 per cent of the overall weight (including services such as education, healthcare, and travel); while housing occupies 10.07 per cent (including costs of housing, rent, maintenance, and utilities).

The government’s fiscal agenda, at least for its medium- to long-term strategy, needs to singularly focus on these three weights — because of which CPI has generally remained high.

The temporality and seasonality of price rise surfacing from the food and beverages component (for vegetables, pulses, etc.) warrants more clearly directed cyclical interventions by the government, which it has failed to do so far.

There have been ad hoc bans and restrictions on export-import good movements which have created a negative business sentiment among agri-traders. Buffer stocks have been used for rationing schemes (for electoral reasons) while the management of the (minimum support price (MSP) system for a diversified food basket has been a disaster, often making MSP-dependent farm groups unhappy.

There is a need for the government to change that perception in this Budget. There will be a big spending challenge though given this government has a ‘coalition tax’ to pay for. The National Democratic Alliance (NDA) allies from Bihar and Andhra Pradesh have already stated their spending demands and preferential aid/status needs for assistance from the Government of India.

Both the BJP allies want the government to allow them to borrow more in the states they govern. Fiscal rules, as per reports, stipulate that states limit their borrowing to 3 per cent of the region’s gross domestic product. Bihar has asked for an additional 1 per cent of headroom with no conditions attached, while Andhra Pradesh has requested 0.5 per cent.

This might affect the government’s spending capabilities in an already fiscally tight and debt-expanding government position. So, the vital macro-observatory point here would be to closely monitor the government’s debt and borrowing levels, which have already been tinkering at a dangerous level. Household debt and corporate debt have been on the rise, while the levels of investment and savings have remained low. These are core Keynesian issues waiting to be addressed for far too long.

The third key issue for the government to address would be to more narrowly focus and design a medium-to-long-term approach for creating ‘good’ jobs in the economy while ensuring a job-based social security/safety net. The government has apathetically ignored the nation’s macro employment fault lines for far too long. This was the other key issue which made a significant chunk of the youth-voter base (in states with high unemployment like Haryana, and UP) vote against the BJP.

Areas where vital, well-organised, labour-intensive jobs can be created, while incentivising existing areas where jobs are already being created, require a strategic pivot in industrial policy thinking, which the current government’s macro-policy advisory space either lacks to advise, or probably wields too little influence to make a difference on policy design outcomes.

The big Make in India and manufacturing-led growth push hasn’t created the employment growth story, which the government would have hoped for (in increasing PLI-centred outlays year after year) and in the process what we see is a government that is fiscally strained in not being able to spend enough money in critical job-security areas (for rural population) in the MGNREGA, or an urban-focused version of the NREGA (the demand for which has been stated for a few years now).

(The writer is professor of economics and dean, IDEAS, Office of Inter Disciplinary Studies, OP Jindal Global University)