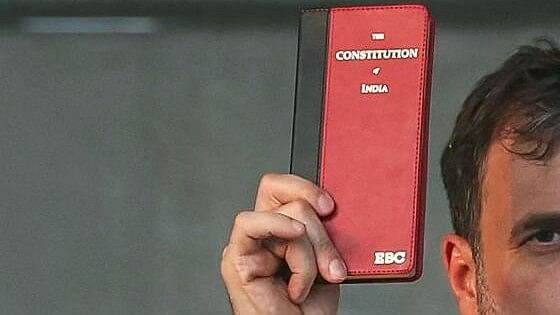

The Constitution of India.

Credit: PTI Photo

The Constitution is widely being debated in the ongoing general elections. A few politicians publicly appealed for votes to change the Constitution. On the other hand, the Opposition has been arguing against changing the Constitution; rather, to safeguard it.

The campaign and counter-campaign around the Constitution have deep connections with the rights of citizens. Reports from the ground indicate a concern among the marginalised about their future as they link the Constitution with the possible affirmative action as well as a safeguard, howsoever weak, from oppressive social structure.

The legal system derives its legitimacy indirectly from people in India, through elections, and it enforces laws through “the threat of state sanctions” as Jürgen Habermas says. The popular consciousness, in this process of creating the law and implementing it, does not necessarily play a significant role. It, however, has historically played an important role when social movements led to new legislation or amendments. The organic connection of people with the Constitution seems lost. The hard work of the Opposition is a testimony to this as they try hard to conscientise masses about the possibilities of the future.

People grow with the idea that they have certain rights and expectations from the State. These ideas are further strengthened by different kinds of ideological apparatuses. There have been mobilisations and movements that strive towards legislative inclusions to improve the condition of people at the margins. There have been also contesting ideas that have legally ensured the withdrawal of the State from its responsibilities.

The debate around the Constitution during the ongoing elections tends to invoke these aspects of contesting political ideas. The political class that seeks full control over the legal-judicial process has started questioning the autonomy of the legal-judicial process to implement whatever policies and ideas it wants. On the other hand, those who want to safeguard this autonomy of the legal-judicial process seek to protect the Constitution. Their intention, if their past is an indicator, may not be for actual social control over institutions, but their ongoing battle cry could establish an organic linkage between the people and the Constitution.

The law-politics relationship has always been there, as indicated by the debates in the Constituent Assembly. This relationship was more an ideological question at the level of what motivates the making of the law and its implementation dealt among the legislators rather than with the masses. Jedediah Britton-Purdy of Duke University School of Law says about the law-politics relationship that we need to “admit the possibility that politics really does come first, that the question is not for or against politicization, but what kind of politicization.”

The post-Independence conscientisation of the masses at the margins and the gradual realisation of a huge section that their rights are being curtailed rekindled the debates on the politics-law relationship. The marginalised section developed a general sense of the Constitution as a protector of provisions of affirmative action and of the rights of the downtrodden. Movements played an important role in this process. There have been numerous occasions when courts have been approached for violations in the implementation of affirmative action, atrocities against the Dalits or freedom of speech among, other things. Judgments may not have been favourable and have raised questions of the law-politics relationship.

Modern law followed the ideas of the liberal revolution of equality, liberty, and fraternity, and included them in its fold. Differences in contexts, defined by the historical circumstances, determined the framing of constitutions. Modern law tries to demonstrate its commitment to equality, and claims to be value-neutral. However, this has been exposed through judges claiming to be members of Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) or contesting elections after resignations or being appointed to various government positions.

The Weberian idea of rational authority under capitalism has been exposed multiple times. Even the law has come under criticisms for being biased and for siding with particular ideologies and socio-economic interests. The supposed rational authority of the judiciary and legal processes has been exposed most recently by open criticism of the judicial process by ministers and even the vice-president. These criticisms did three things: One, established that the judiciary is not beyond politics; two, legal systems are shaped and reshaped by the political establishment; and three, raised valid questions about the legitimacy of legal processes pushing them more within the political domain.

These three elements can be seen at play in the 2024 general elections. As the Constitution becomes a political issue overtly, it also, in turn, finds itself, for the first time, amidst people. The unfortunate part is that electoral processes may not be dictated by rational-legal authority as foreseen by the likes of Weber, and, hence, the Constitution to become a living object might have to struggle.

The onus lies on those who are trying to defend it on grounds of safeguarding its principles of liberty, equality, and justice. Can they push it more as an object that needs popular attention and reflection? Can a sense of ownership towards the Constitution be developed among the masses? Or can the Constitution become a document that constantly speaks to the masses? While the politics has been energised by bringing the document to the masses, it remains whether this politics can make it into an organic document of the masses.

(Ravi Kumar is Associate Professor, Department of Sociology, South Asian University. X: @74kravi)

Disclaimer: The views expressed above are the author's own. They do not necessarily reflect the views of DH.