It is important to distinguish between Brahminism and casteism. Else we will be barking up the wrong tree and not address the actual problems of casteism in today’s India.

It is widely accepted in sociology and anthropology that “caste system” means a set of groups whose entry is determined by descent and marriage regulations, whose members are said to have a traditional occupation, and who have an ideology of hierarchy where some are considered superior or inferior to others. Caste is not limited to India and is found in regions as diverse as Japan and Yemen.

The popular belief that caste means the Varna scheme—that society is divided into a ranked order of Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas, and Sudras—is not fully correct. The Varna scheme and its putative hierarchy do not match the contemporary social reality in several regions. GS Ghurye is one of the early scholars who said that to get a more accurate picture of the caste system, one must look at the relative power and social status of Jatis and not Varnas.

Jatis are endogamous units and include the families within which marriages can, in principle, be accepted. As B R Ambedkar pointed out, Jati membership shapes one’s social networks, determining whom one supports and helps and who is excluded. People place Jatis higher or lower in the Varna scheme, with several Jatis making up one Varna in a region. The Jatis within a particular Varna may vary across different regions. The Varna of a Jati can change with the community’s fortunes. There are a number of Jatis whose Varna location changed as a result of a war or other misfortune. Similarly, there are many Jatis that begin to declare a higher Varna location after getting more land or political power.

M N Srinivas popularised the concept of the “dominant caste” as a way to understand the caste system in different parts of India. For example, in many parts of Punjab, Haryana, and western UP, we find that the caste system has the Jutts and the Jats as the dominant castes in the political, economic, and social structures. When the dominant castes use the symbolism of Brahmins to justify their higher status and power, that can be called a Brahminical system. The symbols of Brahminism have changed over the millennia. Nowadays, prominent among them is to consider meat-eating and the consumption of alcohol as impure and low acts. These do not make up the regional cultural hierarchy in several parts of India. In Punjab, most Jutts would disagree that the Brahmins deserve any respect, whereas in several parts of Haryana and UP, the Jats may concede only ritual respect to them.

What we see in these regions is a caste system because resources are controlled by groups that use endogamy and ideologies of identity to protect their privileges and struggle for more economic, political, and social power. Not just the dominant Jatis, but also the less powerful Jatis, use identity and endogamy to consolidate their strength and resist the depredations of the more powerful. These are flexible processes. People can use marriages and the fusing of identities to strike new alliances when they are beneficial. Since Brahmins are not essential to such a system, it is better to call it casteism rather than Brahminism. Of course, there are other processes like class, gender, religion, and so on that work to shape social inequality, too.

Jatis, which consider themselves Brahmins may be the dominant caste in regions like Pune or parts of eastern UP and Bihar. But in places like Punjab, where Brahmins are largely among the educated, the most powerful set of Jatis are the landed Jutts, followed by the trading Jatis like the Aroras, Khatris, and Baniyas. This domination has a symbolic dimension as well, with many of the Jutts, for example, holding other Jatis in contempt and being unwilling to marry a daughter into them. This is casteism, and it makes little sense to call it Brahminism.

Social exclusion occurs in casteism through the control of resources, power, and culture. The exact structure of social groups practising this varies from place to place. In north-central Karnataka, the most intense use of caste to control, dominate, and oppress is done by the Lingayats, who are the dominant caste there. In the south of Karnataka, this is done by the Vokkaligas.

One argument in favour of calling this a Brahminical system is that in many places, casteism is legitimised by certain Hindu scriptures that place the Brahmins at the top of society. This creates an ideology of hierarchy that defends social exclusion. However, Richard Burghart has pointed out that there exist not one but at least three ideologies of hierarchy in India: that of the Brahmins, that of the Rajputs, who believe themselves to be higher than the Brahmins (“we are manly, and we feed them!”), and that of the ascetics, who believe themselves to be distinct from and superior to the rest.

Veena Das, and others argue that there may actually be several symbolic hierarchies other than the well-known Brahminical one. In Punjab, for example, many Jutts firmly assert that their own cultural practices of eating chicken and consuming alcohol are far superior to “effeminate” practices like vegetarianism. The ideology of hierarchy here is based on the Jutt culture, not the Brahmin culture.

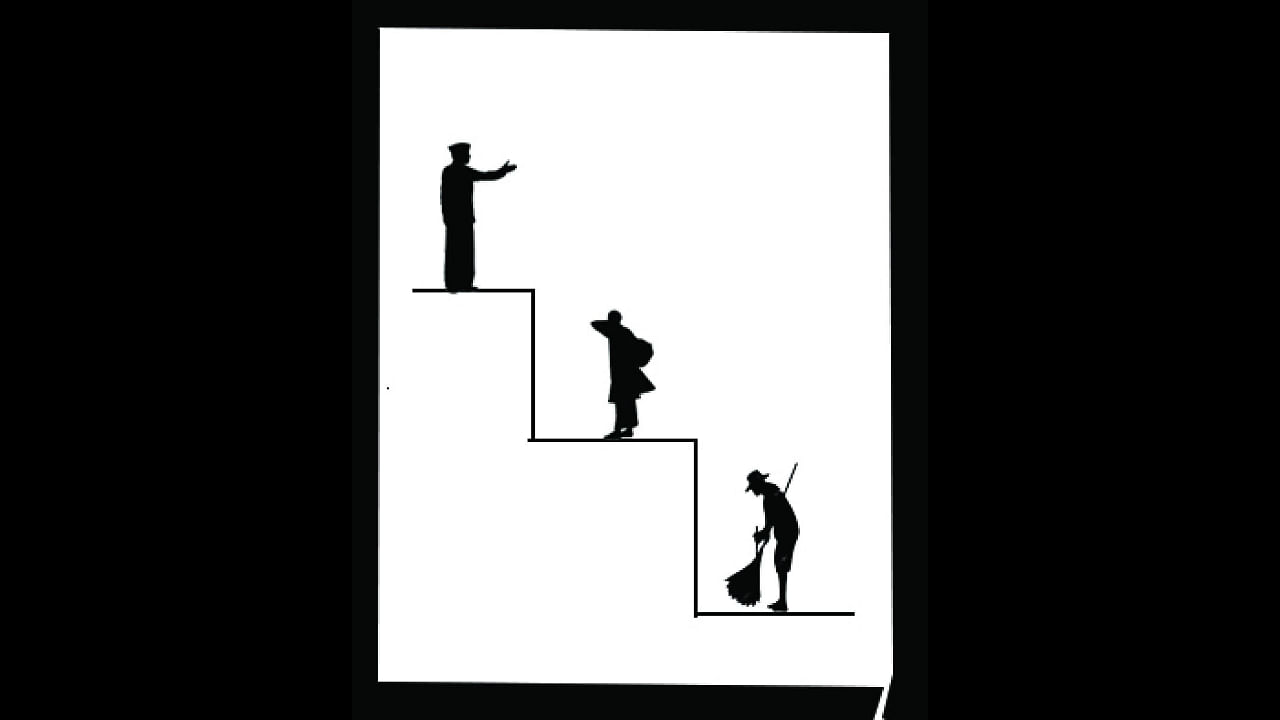

It can be argued that the core of casteism is power, not symbolic hierarchy. Casteism is much bigger than Brahminism. As a system of social closure through marriage restrictions and ideologies of hierarchy, it flourishes wherever it gives political, economic, and symbolic advantages. When practiced by the powerful, it further aids their domination; when practised by the weak, it strengthens their resistance against domination.

Casteism clashes with the needs of a complex industrial society where people must cooperate and work together by going beyond their older identities. It goes against the ideas of freedom and equality, which are needed for people to work together with mutual respect. In today’s times, the forms of caste are changing, and its effects often operate behind the scenes through social networks and cultural domination. Brahminism is only one of the several forms it may take. Ignoring its many other forms prevents us from strengthening human dignity and well-being.

(The writer teaches at Azim Premji University)