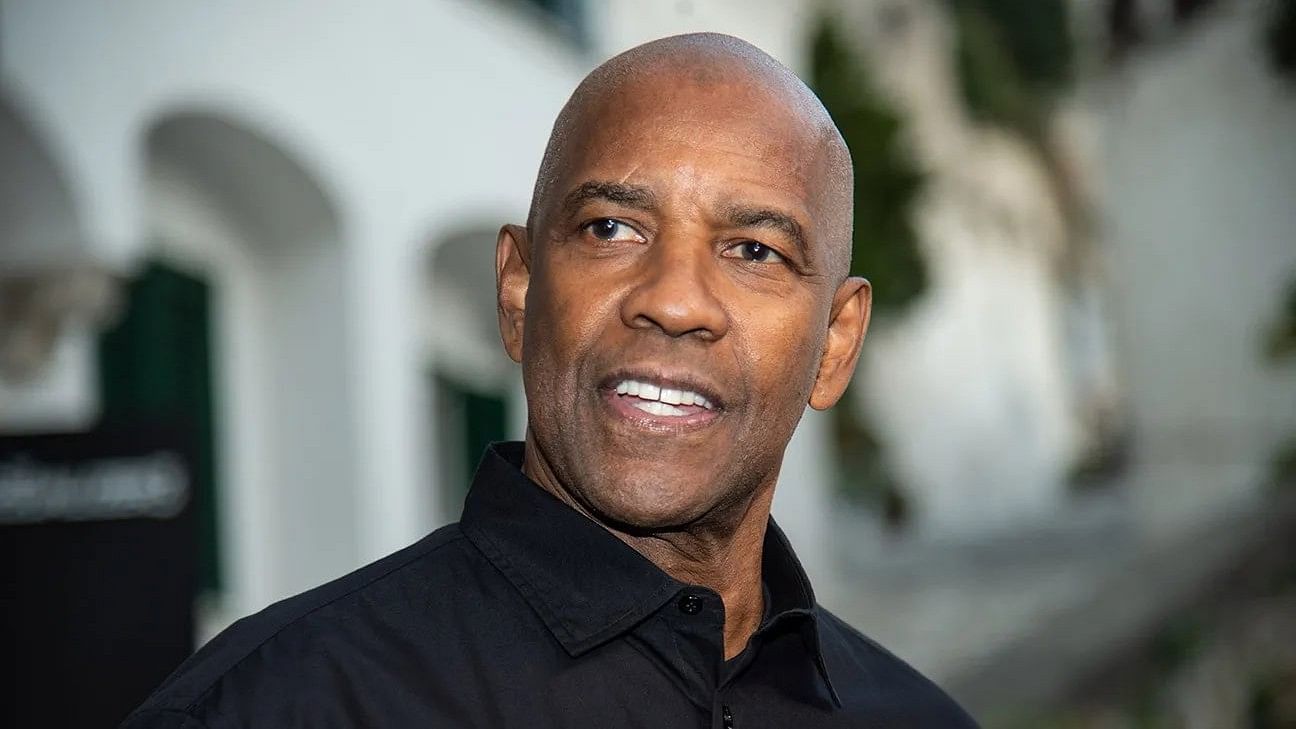

Actor Denzel Washington

Credit: X/@AfricaFactsZone

By Bobby Ghosh

“I carry 23 great wounds, all got in battle; 75 men have I killed with my own hands, in battle. I scatter, I burn my enemies’ tents. I take away their flocks and herds. The Turks pay me a golden treasure, yet I am poor! Because I am a river to my people!”

Anthony Quinn’s blood-and-thunder turn as Auda Abu Tayi in Lawrence of Arabia is one of my oldest memories: I must have been five or six years old when I first saw David Lean’s 1962 masterpiece. For years thereafter I entertained my parents and their friends by declaiming Auda’s soliloquy, one of the finest ever committed to celluloid.

It would take many more viewings over many more years before I became aware of the absurdity of some of Lean’s casting choices for the film’s major Arab characters, Auda, a legendary Huwaitat chieftain is played by Quinn, an American of Mexican and Irish ancestry, and Englishman Alec Guinness portrays Prince Faisal of the Hejaz.

Back then, casting Westerners in big-budget epics about nonwhite historical figures was unremarkable for Hollywood. The excuse usually trotted out was that A-list stars, who were for the most part White, sold more tickets. Easily the most egregious examples of this tendency are 1956’s The Conqueror, in which John Wayne plays Genghis Khan, the mighty Mongol, and 1966’s Khartoum, featuring Laurence Olivier as Muhammad Ahmad, the Sudanese Mahdi.

Quinn himself would develop a fine sideline playing historical Arab heroes, in films like 1978’s The Message, as the Prophet Muhammad’s uncle Hamza, and 1980’s The Lion of the Desert, as Omar al-Mukhtar, the legendary Libyan freedom fighter.

Filmmakers could play faster and looser with fictional characters: To limit ourselves to the cast of Lawrence of Arabia alone, Lean had Egyptian star Omar Sharif portray the Russian lead in 1965’s Doctor Zhivago, and Guinness, again in brownface, as a high-caste Hindu in 1984’s A Passage to India.

But by then, Hollywood was taking greater care in casting nonfictional non-White heroes, acknowledging the importance of some ethnic and/or racial authenticity. Ben Kingsley is unlikely to have been picked for 1982’s Gandhi if he didn’t have Indian ancestry. And happily, blackface had become a thing of the past by the time the studios began to make biopics of great African American figures.

This coincided with the rise of Denzel Washington as a major movie star, whose filmography includes memorable portrayals of Steve Biko, the South African anti-Apartheid activist; Malcolm X, the American civil-rights activist; Rubin “Hurricane” Carter, the boxer wrongfully convicted for murder; Herman Boone, the American football coach; and Melvin B. Tolson, the poet and educator.

So it is doubly disappointing to learn that, in an upcoming Netflix biopic directed by Antoine Fuqua, Washington will play Hannibal, the great general and military genius of Carthage — the area around modern Tunis. The logline, or summary, of the film says it will cover the crucial battles between Carthage and Rome during what is known as the Second Punic War, comprising a series of battles from 218 BC to 201 BC.

Never mind that Hannibal was in his 30s and 40s during that campaign; perhaps some smart makeup and a little artful CGI will cover for Washington’s age, 68. But the inconvenient facts of Hannibal’s race can hardly be hidden. The general was not black African but Semitic. Carthage was founded by the Phoenicians, who came from the eastern Mediterranean coast, roughly corresponding to modern Lebanon, Syria and Israel.

Inevitably, the casting of Washington for the part has roused hackles in Hannibal’s birthplace. It was brought up in the Tunisian parliament by Yassine Mami, president of the committee on tourism, culture and services. The culture minister, he said, “should take a position on the subject. This is about defending Tunisian identity and listening to the reactions of civil society.”

The minister, Hayet Ketat Guermazi, took a more realistic view. “Hannibal is a historical figure, even if we’re all proud that he [was] Tunisian… what could we do?” she said. “What matters to me is that they shoot even one sequence in Tunisia and mention it.”

Her pragmatism stems from the knowledge that Tunisia, with just 12 million people, is unlikely to get much traction with the panjandrums of Hollywood. A studio wouldn’t dare cast, say, Matt Damon to play the Qianlong Emperor, one of China’s greatest leaders, or Jamie Foxx as Ashoka the Great of India. The Chinese and Indian markets are too large and lucrative to risk giving offense.

But when it comes to smaller markets, filmmakers know they can get away with lazy or stunt casting. Netflix has priors on this, having ignored Egyptians protests to cast a Black actress as Cleopatra. Although ancient Egypt was a melting pot of races and ethnicities, Zahi Hawass, the country’s preeminent archeologist, and other historians say the queen was very likely Macedonian Greek.

Can Netflix, Fuqua and Washington get away with fudging history? And will history, in turn, forgive them for it? It’s useful to remember that A Passage To India, David Lean’s last film, was a critical and commercial success, but is today remembered mostly for the miscasting of Guinness and arguably the actor’s worst performance ever.

History can be a harsh critic.