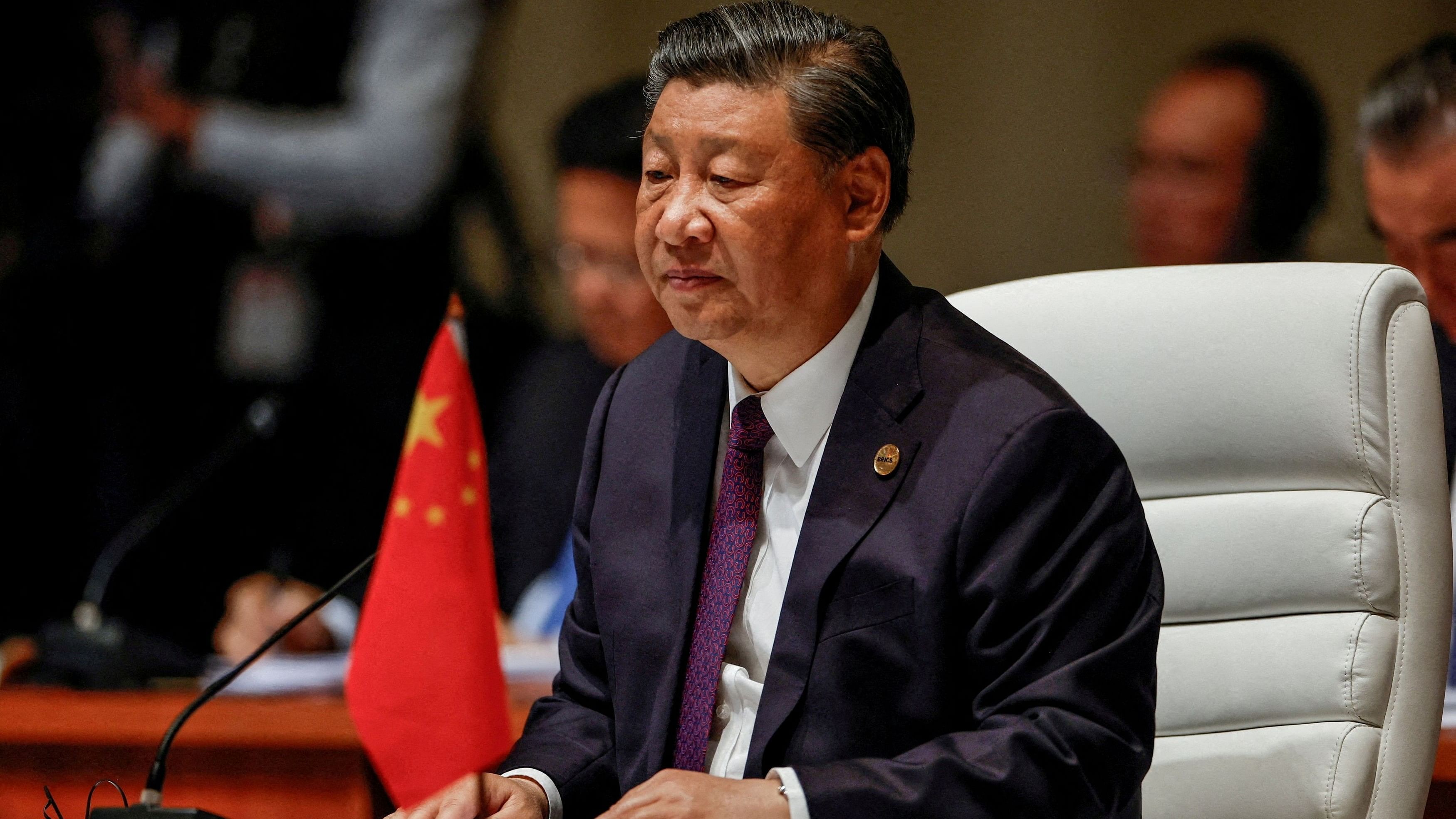

Chinese President Xi Jinping.

Credit: Reuters File Photo

China’s rise as a global power has been accompanied by a distinct expansionist strategy, of which the map recently released by China’s Ministry of Natural Resources is a reminder. China employs several strategies to satisfy its expansionist urge, such as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), debt-trap diplomacy, salami slicing, cabbage-wrapping, and the string of pearls. These strategies show China’s ambition to reshape and restructure the global order.

At the heart of China’s expansionism lies Xi Jinping’s pet project, the BRI. An ambitious infrastructure project aimed at reviving the ancient Silk Route connecting Asia, Europe, Africa and Australia, the BRI has garnered participation from over 100 countries, making it one of the largest development initiatives in history. Its primary goal is to enhance China’s economic and political influence by creating a vast network of railways, energy pipelines, highways, and ports, thereby facilitating trade and connectivity across continents.

BRI is a tool to expand the Chinese sphere of influence and obtain leverage over countries that can be exploited for geopolitical gains.

China’s BRI and debt-trap diplomacy go hand in hand. By providing soft loans and financing for projects in developing countries, China can exert influence over them to fulfil its expansionist ambitions. Countries like Sri Lanka and Pakistan have experienced debt-trap diplomacy. In Sri Lanka, the inability to repay loans for the Hambantota Port project resulted in China taking possession of the port on a 99-year lease, raising concerns over Sri Lanka’s national sovereignty. Similarly, in Pakistan, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor has led to a significant increase in debt, raising questions about the long-term implications for Pakistan’s economic independence and strategic autonomy.

China’s salami-slicing strategy is another key part of its expansionist strategy. Beijing uses incremental territorial advancements through small, seemingly insignificant, actions that, when combined, result in strategic gains. By avoiding confrontation and operating below the threshold of armed conflict, China gradually expands its control over disputed territories without triggering a strong response from its adversaries.

According to Brahma Chellaney, the countries who are victims of China’s salami slicing are presented with a Hobson’s choice, either to silently suffer small incursions or risk an expensive and dangerous war with China. Beijing has used salami slicing in Aksai Chin against India, and in the South China Sea to acquire Paracel Islands, Mischief Reef, Johnson Reef and Scarborough Shoal. This strategy has generated tensions with India, Vietnam, the Philippines and Malaysia, as well as drawn the attention of the US to China’s desire for dominance in the region.

‘Cabbage-wrapping’ is a variation of salami slicing that involves surrounding a contested area with a multitude of vessels, effectively enveloping it in layers akin to cabbage leaves. This strategy aims to create a physical and psychological barrier, making it difficult for opposing forces to access or challenge the disputed territory. China’s use of cabbage-wrapping has been most evident in the East China Sea in its territorial dispute with Japan over the Senkaku Islands. China has also used cabbage-wrapping over Pagasa Islands, Ayungin Island and Scarborough Reef (previously under the Philippines).

The ‘string of pearls’ is a term used to describe China’s efforts to establish a network of strategic maritime outposts across the Indian Ocean to protect its trade interest and establish dominance in the region. These outposts, which include ports, naval bases, and facilities for refuelling and resupply, serve as potential logistic hubs for China’s naval operations and enhance its ability to project power far beyond its shores.

China’s strategic investments in ports such as Gwadar in Pakistan, Hambantota in Sri Lanka, and Djibouti in the Horn of Africa, have raised concerns in India, the US and others. With its ‘string of pearls of port projects and naval bases, China is seen to have encircled India in the Indian Ocean region. These facilities could provide China a way to neutralise India’s military advantage in the region as well as extend its influence.

China’s expansionism threatens the current global order. Its assertiveness in territorial disputes, use of debt-trap diplomacy, and establishment of strategic outposts raise concerns about the erosion of sovereignty, the potential for military conflict, and the shifting balance of power in critical regions. This expansionist strategy by China represents a multifaceted approach aimed at establishing China as a global power. Understanding the intricacies of this strategy is crucial to efforts to maintain a stable, rules-based international order in the face of the Chinese challenge to it. India will need to strengthen its military capabilities, regional cooperation, and alliances and partnerships to counter China’s aggressive expansionism.

(Lalitha is postgraduate student, Central University of Kerala; Kumar is Head, Department of International Relations, Peace and Public Policy, St Joseph’s University)