Since the pandemic was declared, there have been reports on the dismal state of health infrastructure and lack of protection for health workers as we take on this crisis. Almost two months later, the situation has not improved, and it appears that we have collectively, as a society, turned away from this harsh reality. Our doctors and nurses are not going to be saved by clanging pots or paeans of praise that can hardly compensate for the trauma of having to stand on duty on the front line of this war against COVID-19 with inadequate personal protective equipment (PPE).

Among other gaps and deficiencies encountered as we face this health challenge, this shortfall of protective gear was flagged urgently and repeatedly. It was endorsed as a critical need in all policy documents and guidelines from WHO to the Union Health Ministry and right down to the level of hospitals and fever clinics. At this point, meagre supplies are running out and replacements have not arrived, leaving the hospitals with a secondary crisis: either close down or expose their doctors to risk. While the former would be catastrophic, the other option is equally unjust. There have been suggestions to improvise, create reusable gowns and masks, homespun visors, and other makeshift solutions until stocks arrive. This is severely testing the resolve of even the most dedicated doctors, and their duty to care.

This careless attitude is an assault on the dignity of the profession; one that is still reeling from the abuse and violence targeted against it by frustrated and angry patients, themselves victims of a broken system, with no recourse to assistance. This pandemic is hurtling towards another confrontation, as doctors find themselves abandoned in this war against a virus that can threaten their health, and through them, their families and other patients.

The reference to war and frontline is not accidental. As a society, we fully support our jawans and battalions protecting our borders and defending us from external danger. It would be unacceptable if they did not have protective clothing and gear to survive on the Siachen glacier, or were expected to face an encounter without helmets, tanks or weaponry. Now, the threat is within our borders, invisible yet potentially devastating, bringing the entire country to a grinding halt, and we appear content to have a different standard for our health professionals fighting for lives at the frontline of this crisis. The expenditure of the government on defence is more than three times its outlay on health. Over time, this has led to the neglect of the health sector, and denial of access to care for millions.

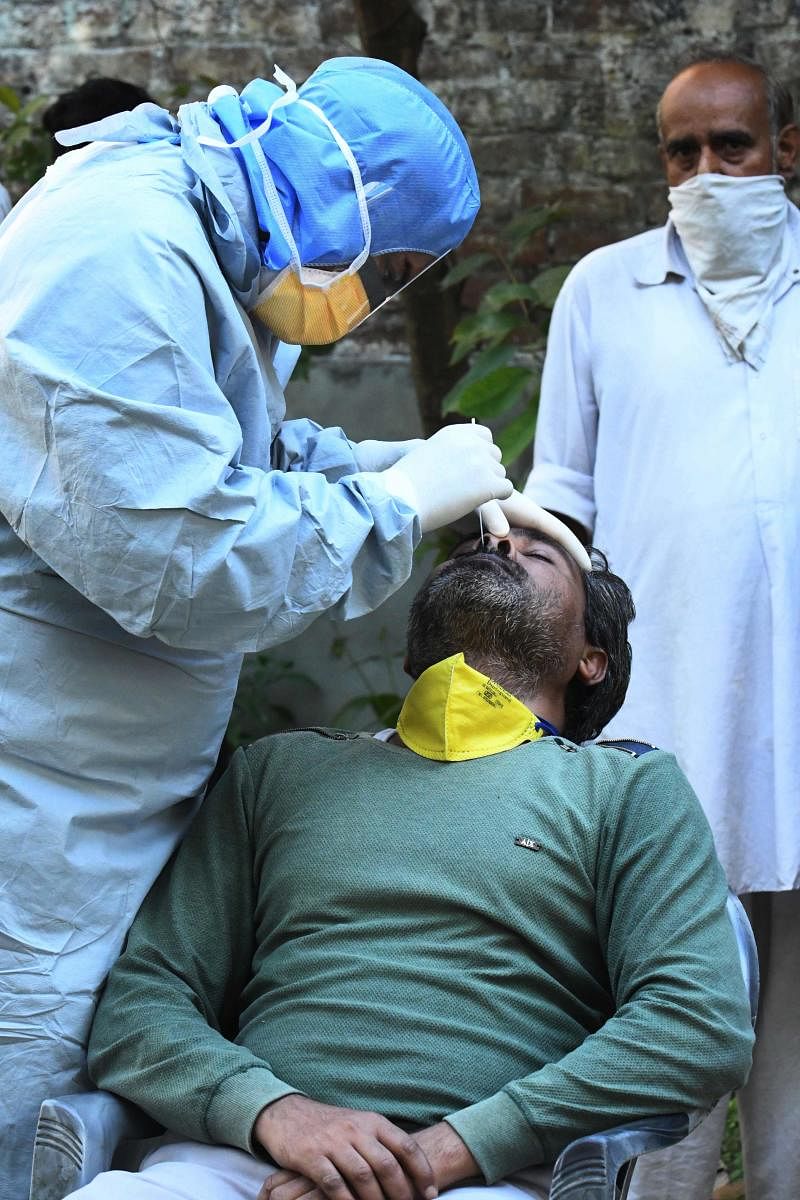

The Covid-19 crisis has confronted us with the painful reality of our inadequate health infrastructure. If healthcare is an essential service, then health professionals are an essential element to be protected. Is this not the duty of the government in the case of public hospitals, and of the management of private hospitals? Can they be held responsible? While doctors have been holding the line so far, it will not be in the best interest of patients to put this sense of duty to the test. Scores of doctors and nurses are falling ill and the death count has begun. We need the best-trained in the ICU, OT and emergency room as triage and allocation of resources requires expertise. Protective equipment has been prioritised to this high-risk segment where exposure is highest. Scarcity has led to the exposure of ancillary health workers, cleaners and helpers to risk, as limited equipment is reserved for doctors. This inequitable treatment of health workers should not be allowed.

This has not been the experience in other Asian countries. China ramped up its production capacity of PPE 20 times over in one month; now, it is even able to export to other countries. There has been no coherent plan here for either manufacture or import of PPE, sanitisers or masks, and it is now obvious that health workers have to fend for themselves in most cases.

The impact on medical care and professionals is undeniable. Doctors need PPE to feel safe and remain effective under crisis conditions. Working overtime in hazardous conditions has led to exhaustion and stress. At a time when patients with symptoms are afraid and anxious, they need a professional presence and reassurance to overcome this illness. The quality of attention and medical care can be severely compromised if the health worker is afraid of infection and has to work with inadequate supplies and protection.

Faced with a chronic shortfall in quality and access to health services, we have become numb to the appalling conditions under which our doctors are practising in many parts of the country. The question is, for how long are we willing to accept this, and if we pass this opportunity to set things right, will it be at our own peril? A recent poll of young doctors and medical students revealed that 65% felt it was not wrong to refuse to work if adequate PPE is not available. Should doctors have to face such a dilemma during this crisis? It is not hard to imagine that we might lose our doctors to countries that promise better working conditions, and the medical profession itself could lose its sheen as a career choice.

(The writer is Adjunct Faculty, Division of Health and Humanities, St John’s Research Institute, Bengaluru)