Psephology is a discipline that does quantitative analysis of elections and the voting behaviour of people. Though like other disciplines it also attempts scientific prediction, it seldom makes an effort to get into the ‘mind’ of the voter, what an average voter thinks when she goes to cast her vote, either by ballot or by the EVM. ‘Undecided’ voters and their last-minute decisions are seen as ‘swing’ in the votes and largely affect the conversion of percentage of votes into the seats won by any political party.

How does an average voter, not loyal to any particular ideology, decide whom to vote for? A complex interplay between an individual’s attitude, social factors, and the campaigning done by political parties and candidates impacts the decision of the voter. Electoral psychology, another emerging discipline, may help us to map, gauge, and predict the voter’s choices and voting patterns. However, some inputs from classical psychology and ‘effects’ propounded also help reflect on the average voting pattern over the last decade. We

are suggesting a perspective from the vantage point of voters making choices for clear majorities and repeating certain governments.

Barnum-Forer Effect

This effect is a fallacy of personal validation. Some Barnum statements that are general characterisations attributed to an individual are perceived to be true for them; they are applicable to almost anyone. These are generally used by astrologers, such as ‘you do not want

to hurt anyone but somehow it happens’ or ‘you believe people and trust them easily and they betray you at the first opportunity’.

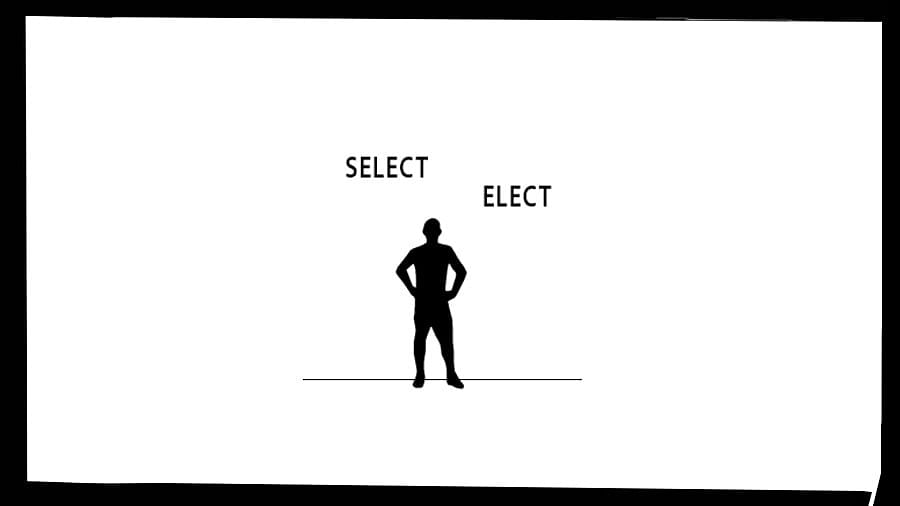

Similar statements are replete in any political leader’s campaign speech. Such as, ‘you are the voter who will chart the destiny of this nation’ or ‘like me, you have been wronged by all others and you must not believe anyone but yourself’, these statements uttered by a politician instantly establish him/her as the very extension of the voter and make the latter to select self rather than to elect.

Confirmation Bias

The three cleavages of religion, gender and class also affect voting patterns and political parties and candidates exploit this to the hilt. From ‘Gareeb ka beta’ to a proud nationalist to someone having the broadest masculine chest again establish an ‘apophenia’ with the voters. Apophenia is a tendency wherein people start to see relationships between unrelated things, such as ‘someone born poor will definitely be honest’ or ‘someone who thumps his chest and proclaims his masculinity will be a decisive leader’. But these are the biases which lead a voter to ‘empathise’ with the speaker, and again, the voter selects a leader or contestant who confirms her own prejudices and biases.

This is also the case when a candidate says things that a voter also believes to be true. For example, if a candidate says that ‘my God, say God A, is better than the Gods of others, say God B and God C’. In this case, all the voters who believe in God A will most likely select this candidate as he is confirming what they already believe. This is a clear and obvious reason why politicians use or focus on religion or faith on many occasions, in many countries. It has also been found that such voters often experience heartbreak as politicians fake religious positions and values just to lure voters to their side.

The Placebo Effect

The placebo effect is when a person’s physical or mental health appears to improve after taking a placebo or ‘dummy’ treatment. Placebo is Latin for ‘I will please’ and refers to a treatment that appears real but does not have any therapeutic benefit. In elections, it may be understood as the selection of a person who is ‘new’ in appearance, ideology or promises. People often get bored and dissatisfied with the present set of people and ideas in government. If some new person looks different and makes interesting promises, he or she may be selected by people just to try something new. When it happens to a good number of people, it may cause political upsets.

Hawthorne Effect

This effect explains how people modify their behaviour when they think or know that they are being ‘observed’. Despite the ‘closed’ space of a balloting area, people have been given the idea by 24X7 news channels, internet, social media platforms that they are being observed, and no one wants to be identified as a ‘black sheep’. This was exploited a few decades ago to target a voter who wanted to select a communal ideology. Now, the same has been flipped to target people for not selecting ‘nationalist’, ‘honest’, ‘charismatic’ leaders or for selecting someone else.

The above effects can be produced and generated by the media and social media in the 21st century, when elections are not fought out in the field but rather ‘selections’ are made based on available options projected in the blue light of TV and mobile screens. It is for this situation for which the French sociologist Jean Baudrillard said that it is these simulations that create a ‘simulacra’, where representations are created that do not refer to any original reality. It is in these times that we mistake demagogues as democrats, authoritarians as decisive leaders, and imperialists as nationalists.

Though absolute democracy sounds hypothetical, it is in this form only that the interests of the majority get prioritised while the needs and rights of the marginal and the minorities suffer. The tyranny of the majority is the highest cost of democracy, but if we persevere to be rational, we may be able to differentiate between ‘selecting’ and ‘electing’ a ‘government of the people, by the people, for the people.’ Democracy will survive only when we elect rather than select.

(Sharma teaches at the Central University of Himachal Pradesh; Singh teaches at MJP Rohilkhand University)