The Economic Survey 2023-24 proposed that the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) should consider setting its inflation target without factoring in food prices. The main argument is that the food inflation is mainly driven by supply side factors. India has been facing high food inflation for quite some time and it has emerged as a significant concern for both households and policymakers.

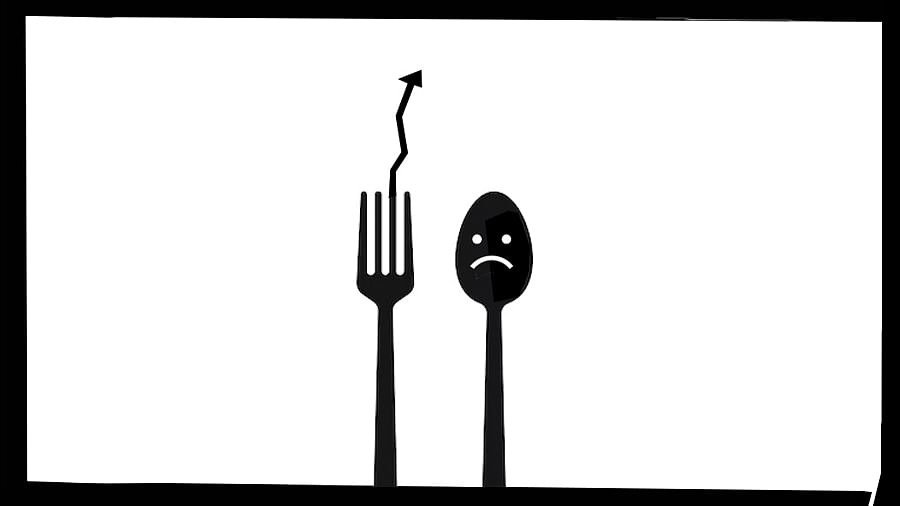

In mid-2023, the Consumer Food Price Index (CFPI) saw a sharp rise, spiking to 11.5 per cent in July from 4.5 per cent in June. This increase was driven by increasing prices of essential commodities like vegetables, cereals, pulses, and milk. Tomato prices skyrocketed by over 400 per cent during the summer months due to supply disruptions caused by erratic weather and logistical issues. For a low-income family, this meant having to make painful choices between buying vegetables and other necessities.

The situation is further complicated by several issues affecting staple crops. Wheat production fell by 3 per cent in 2021-22 due to unseasonal rains and pest infestations. Adding fuel to the fire, fodder prices have doubled over the last two years, rising from Rs 3.5 to Rs 6.5 per kg. This increase has had a direct impact on the cost of milk and other dairy products, with the cost of a packet of Amul milk having risen by Rs 2 since.

It is not just milk that has become more expensive -- paneer, yogurt, and all other dairy-related food items, which are often relied upon as accessible sources of protein, have also seen price hikes. For many families, who are already spending a significant portion of their income on food -- about 46 per cent in rural areas and 39% in urban areas (as per the Household Consumer Expenditure Survey (HCES) 2022-23), these rising costs can be devastating. When food prices increase, low-income families are forced to make difficult choices, cutting back on essential nutrition or other necessary expenses.

A recent report by Michael Patra, Deputy Governor of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), and his co-authors, published by RBI, sheds light on the gravity of this issue. Between 2016 and 2023, food inflation accounted for a staggering 43 per cent of the average headline inflation. What makes food inflation particularly concerning is its ‘sticky’ nature. Unlike other goods, where prices might go up and down, food prices tend to remain high once they go up, largely due to factors like supply chain issues, poor harvests, or rising input costs. This persistence in food inflation does not just affect what we pay at the grocery store, its impact is seen everywhere in the economy.

While core inflation traditionally excludes food prices to focus on more stable trends, the impact of rising food costs cannot be ignored. Higher food prices push up the cost of living, leading workers to demand higher wages. Businesses facing increased costs for agricultural inputs and transportation due to food inflation also raise prices for non-food items. These interconnected effects mean that food inflation indirectly pushes up core inflation as well, creating broader inflationary pressures that affect everything from the cost of everyday goods to long-term economic stability. Furthermore, certain food items such as cereals, milk, pulses, and prepared meals, show a high degree of price persistence. When these prices rise, they tend to stay high, leading to sustained inflationary pressure.

A deeper introspection is needed at this juncture. The proposal to omit food inflation warrants a question: Has monetary policy been effective in keeping core inflation below the target? If one were to examine the last 10 years’ data, except for a few brief periods, it has mostly been above the threshold set by RBI. Therefore, what we require now is a different outlook on this problem. Policymakers must look beyond standard economic models and consider the real consumption patterns and hardships faced by the populace.

Data from the HCES 2022-23 reveals a stark picture: Only 0.2 per cent of the population spends more than Rs 1,000 a day, while about 33.8 per cent of the population spends less than Rs 100 a day. What does Rs 100 buy you today? Perhaps two square meals, if you’re lucky. Rising food prices is not just an economic issue, it is a human issue. For many low-income families, food inflation is not just a minor inconvenience; it can mean the difference between a nutritious meal and going hungry.

According to a report by the IMF, authored by Rahul Anand and Volodymyr Tulin, there is emerging evidence that significant second-round effects (headline inflation feeding into core inflation), are becoming more apparent in emerging economies. This phenomenon is driven by several factors: the high proportion of household expenditure allocated to food, less firmly anchored inflation expectations, and persistent supply shocks.

These factors are particularly evident in India, implying that headline inflation, especially food inflation, feeds into core inflation. Addressing these deep-rooted issues requires more than just adjusting interest rates. It demands a holistic strategy that includes improving agricultural productivity, building robust supply chains, and ensuring equitable access to resources. The effectiveness of monetary policy is often limited in such contexts because it mainly influences demand side factors, while food prices are heavily affected by supply side issues like weather conditions, crop failures, global commodity prices, and logistics.

Therefore, a comprehensive approach that combines monetary policy with targeted fiscal measures, enabling structural reforms to enhance food supply stability is essential. This would help in anchoring inflation expectations and controlling spill-over risks.

Food prices are more than just figures on a chart. They are the very foundation of life for millions of Indians. For many, the cost of food is directly tied to their ability to meet basic needs, making it much more than an economic indicator. This is why it has become a sensitive matter, and a holistic approach that considers both core and headline inflation, most importantly including the impact of food prices, is vital. Such an approach ensures that economic policies are not just technically sound but also fair and considerate of the everyday struggles people face.

(Omkar Patil is a student at T A Pai Management Institute, Manipal;

Dr Vijay Victor is Assistant Professor, IIT Roorkee)