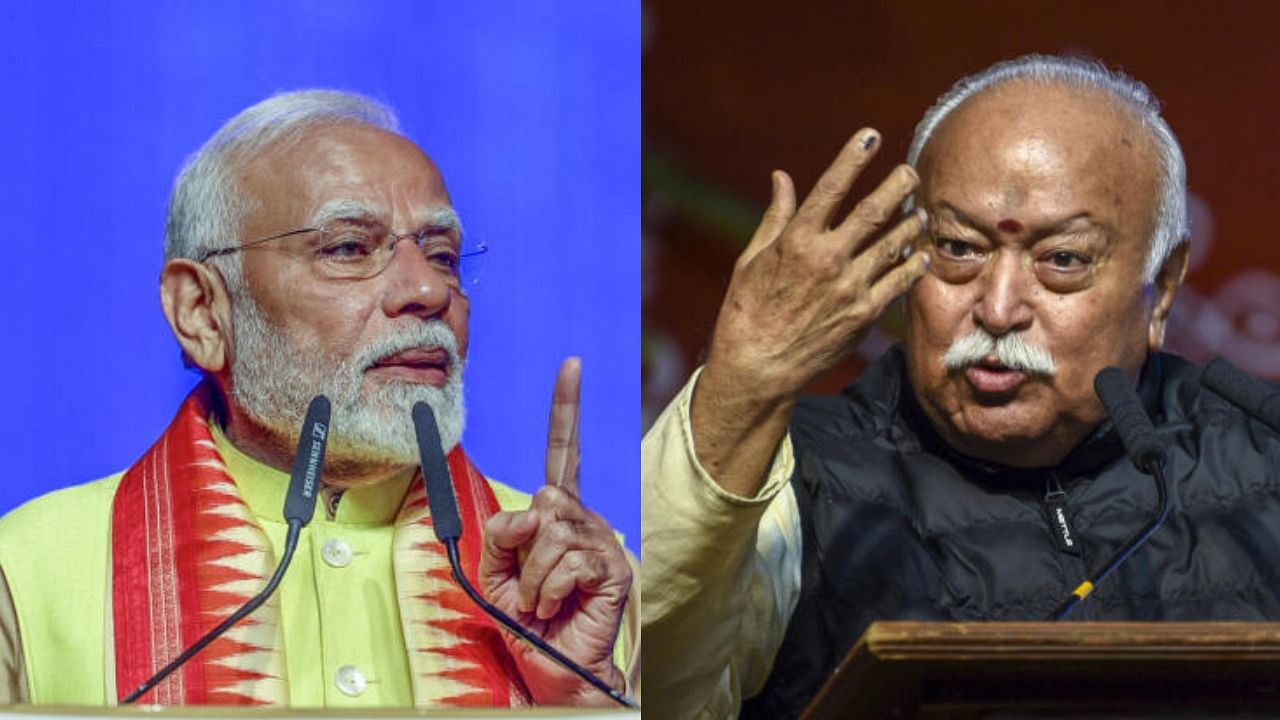

Narendra Modi and Mohan Bhagwat (L-R)

Credit: PTI Photos

The contradictory interplay between vyakti (individual) and the sangathan (organisation) remains an unresolved tangle within the Sangh Parivar, and has repeatedly brought matters to a head, including in the Narendra Modi era after 2014.

The Maharashtra Assembly election verdict seemingly heralds another decisive turn in the often-awkward relationship between the prime minister and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) leadership. Unlike in the past decade, this time, however, on the face of it, the tense phase has eased at a disadvantage to Modi.

To comprehend the current situation, it is necessary to step back into history when Modi first took charge of a public office — of the Gujarat chief minister — in October 2001. Prior to Modi, only a handful of Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) leaders were RSS pracharaks before holding public offices; Atal Bihari Vajpayee, Lal Krishna Advani, Sunder Lal Patwa, and Rajnath Singh were among the handful of such pracharaks.

In the late 1990s, while visiting the United States, Vajpayee famously declared, “once a pracharak, always a pracharak.” Yet, he did not have a very harmonious relationship with the RSS leadership.

Likewise, Modi frequently referred to his not-so-affluent family background and days as an ordinary RSS functionary. He also publicises of being beholden to the organisation for enabling him to learn the basics of governance.

Modi told me when I was researching for his biography that he “learnt from the Sangh the basic skill of running an organisation," and that he picked up the tricks of governance because of being trained "to use manpower resources to the hilt...identifying a team, building it, get the team to do the work.”

But Modi has not chosen to follow all lessons learnt — most importantly to underplay the individual and promote the organisation, party or government.

Modi assumed the CM’s office after the party leadership directed Keshubhai Patel to resign. He knew the routine within the Parivar — even Vajpayee failed to have his way in 1998 and include Jaswant Singh and Pramod Mahajan in the first NDA government because they lost from the Lok Sabha constituencies they contested.

The RSS leadership did not wish to set a precedent of appointing defeated leaders as ministers. This message was not sent discreetly, but done in public glare. A senior RSS functionary, K S Sudarshan, later the sarsanghchalak, visited Vajpayee with the diktat to make Yashwant Sinha finance minister and drop the defeated duo from the list of leaders, scheduled to take oath as ministers the next morning.

With this as the backdrop, senior RSS functionaries in Ahmedabad, expected Modi to visit and consult them on governance and policies.

However, he ran the state unilaterally and with time consolidated all decision-making powers in the Chief Minister’s Office. He followed a similar practice after becoming the PM, although initially, Union ministers were ‘invited’ by the RSS for consultative meetings.

With time, he began referring to the government as ‘Modi Sarkar’, a phrase he dropped after June 4, and began terming it ‘NDA Sarkar’.

The RSS played a major role in the BJP’s failure to secure majority for the third consecutive election. For most of the decade after 2014, the RSS brass was uncomfortable about Modi’s style of working, but looked the other way because he remained ideological committed and implemented the Hindutva agenda squarely.

In complete personalisation of elections and politics, the slogan — ‘Modi ki Guarantee’ proved too much. Not paying scant regard to suggestions during candidate selections also majorly led to the Sangh’s aloofness during campaigning.

Yet, he remained overconfident that his objective of an NDA tally of 400+ would be met. In a move that further antagonised the RSS, BJP president J P Nadda declared — presumably with the approval of Modi and Amit Shah — that the party had outgrown the need for the RSS and that it was now “competent”.

The juxtaposition of the verdicts of June 4 and November 23 underscores the electoral capacity of the RSS, not just in terms of the spectacular change in the tally of the BJP and its allies in Maharashtra, and previously in Haryana, but also that these results were achieved without intensive campaigning by Modi.

Crucially, assertions in late October, by RSS sarkaryavah Dattatreya Hosabale, after an important meeting of a decision-making body of the RSS in Mathura, provided indication of change in the Modi-RSS narrative.

His statement heralded scaling down of an acerbic phase of relationship between the two, during which sarsanghchalak Mohan Bhagwat made several scathing diatribes, which left little to imagination, although he did not name anyone.

The first sign that the BJP still ‘required’ the RSS came when Nadda attended the first RSS co-ordination meeting in Palakkad, Kerala, after the Lok Sabha polls. Hosabale mentioned to the media that Nadda’s statement had been duly noted by the RSS and that, “There is no tension. If something happens within the organisation, we know how to fix it.”

This ‘fixing’ was done by RSS extending unqualified support to Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath, who is certainly not among Modi’s aides.

After the Lok Sabha verdict, the Modi-Shah duo tried affixing responsibility on the party’s poor performance in UP on Adityanath and replace him. The party’s excellent performance in Assembly bypolls with Adityanath in charge is a snub to Modi.

Furthermore, the RSS endorsed a controversial statement — ‘Batenge to katenge’ (will be slaughtered if we are disunited) made in the context of Bangladesh by Adityanath.

This led to various BJP leaders, including Modi, rephrasing the assertion and converting it into the majoritarian slogan that became the cornerstone of the BJP’s campaign in Maharashtra, as well as Jharkhand.

The RSS factor was again evident in the central role played by Devendra Fadnavis during the Maharashtra campaign. The RSS factor is also likely to be unmistakable when selecting the next BJP president. It is doubtful if a choice can be made by Modi and his aides, without consulting the RSS.

Till the end of 2023, it was often said that Modi was weakening the RSS and that the one-time Big Brother had ceased being one. While Nagpur-based leaders may not have regained their dominant position, in the months ahead, Modi’s unilateralism should be now a trait of the past.

From being a ‘settled’ issue with the RSS in the backseat, developments in the recent months will require close tracking of this uneasy relationship.

(Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay, a Delhi-based journalist, is author of 'The Demolition, The Verdict and The Temple: The Definitive Book on the Ram Mandir Project'. X: @NilanjanUdwin.)

Disclaimer: The views expressed above are the author's own. They do not necessarily reflect the views of DH.