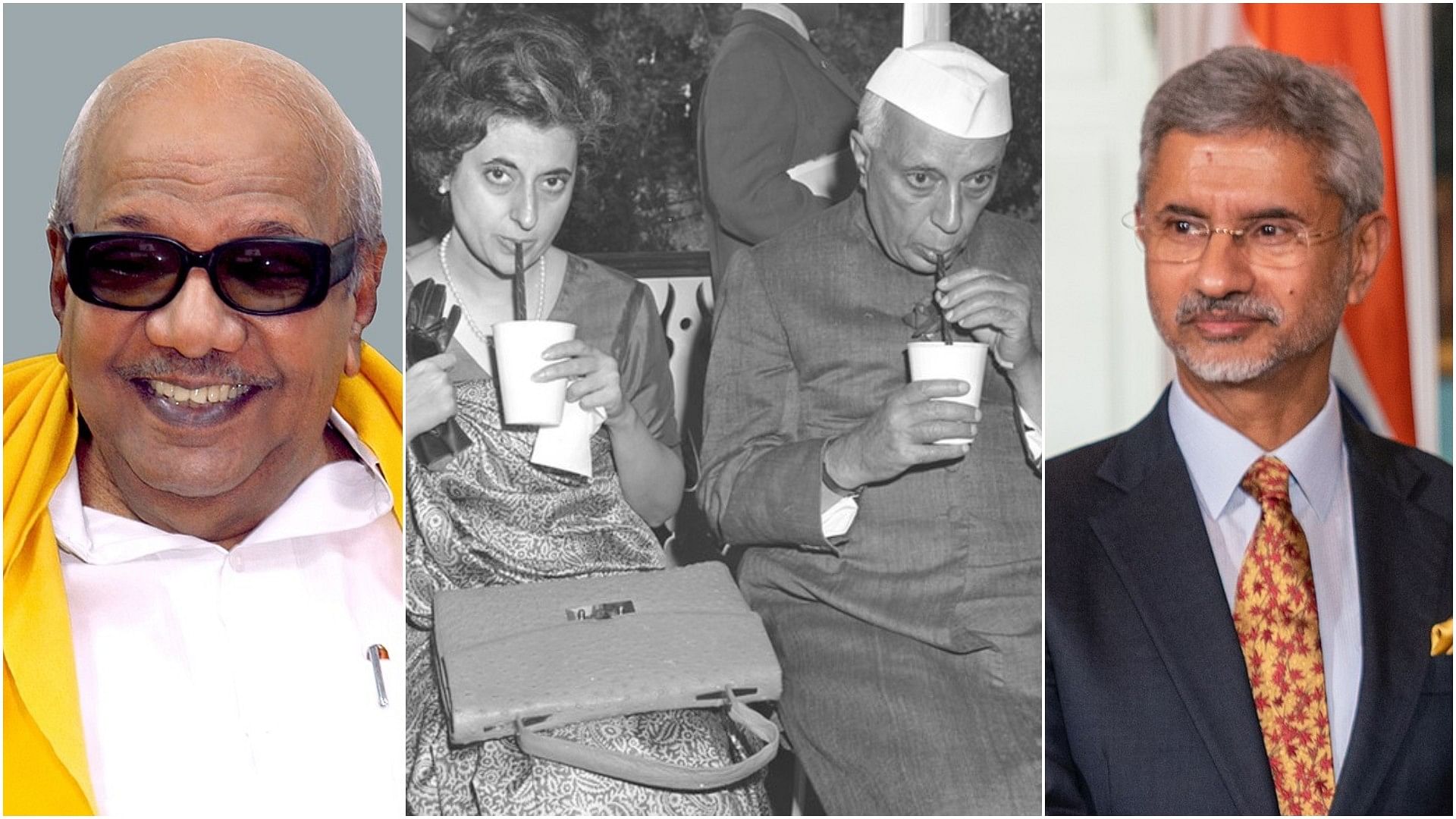

M Karunanidi, Indira Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru and S Jaishankar.

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

The 30-minute media briefing by External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar on April 1 regarding the Katchatheevu controversy was an excessive indulgence during the election cycle for the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) to make some inroads into what seems a hopeless situation in Tamil Nadu.

That alone probably explains the minister’s selectivity to edit the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) archives to create a certain narrative and taking care to speak from his party office rather than use his ministry’s opulent infrastructure to conduct public diplomacy and educate the Tamil public opinion on the ‘whole truth’ why Indians cannot catch fish in the troubled waters around Katchatheevu.

Katchatheevu is one of those issues in regional politics and India’s foreign policies where the dialectics of diplomacy and statecraft, hopeless as it is already, are also intertwined with time — time past, time present, and time future. The heart of the matter, succinctly put, is that the Katchatheevu Agreement of 1974 on maritime boundary falls neatly in the ebb and flow of time between the 1964 Sirimavo-Shastri Pact on the status and future of the people of Indian origin in Ceylon and the explosive eruption of the apocalyptic Sri Lankan Civil War in 1984 and India’s wanton interference in it.

The balance of power approach in international relations in South Asia inevitably involved an interplay of variables. In a masterly treatise available in Australian National University archives on this topic written by eminent Sri Lankan scholar-diplomat Shelton Kodikara (who served as Deputy High Commissioner in Madras during 1975-1977) titled Strategic Factors in Interstate Relations in South Asia, he viewed the paradigm through three interdependent variables: India-Pakistan power rivalry, involvement of major powers in the politics of South Asia, and the interaction of small powers in the subcontinent in the context of the other two variables.

Kodikara wrote that “a connection can be established between the central balance of power and the regional balance in South Asia”, and discerned two main considerations — “first, competition among major powers for support-bases among South Asian states in the context of their own global rivalries; second, competition among South Asian states themselves for political, diplomatic, economic or military support from the major powers, which would redress imbalances and inequalities perceived to exist in their mutual interstate relations.” He saw this as particularly relevant to the India-Pakistan situation, and to a lesser extent also to the cases of Sri Lanka and Nepal. This is the first thing.

That apart, Jaishankar should have brought into his analysis the Atal Bihari Vajpayee government as well instead of taking vicarious pleasure in rejecting Jawaharlal Nehru, Indira Gandhi, and M Karunanidhi. After all, what prevented Prime Minister Vajpayee from correcting the ‘indifference’ by Nehru and Indira Gandhi on Katchatheevu during his years in power as Prime Minister and external affairs minister?

Simply put, BJP leaders weren’t traditionally rabble-rousers. Going a step further, it is entirely conceivable that successive Congress governments not only took the DMK into confidence but other political parties as well — informally and off-record, which is not unusual.

It is worth recalling an episode in 1993 when in the aftermath of the destruction of Babri masjid and the riots that followed, then Prime Minister P V Narasimha Rao took a risky political decision to travel to Tehran against the backdrop of the massive uproar in the Muslim world, to seek Iran’s help to defeat a concerted OIC move (backed by western NGOs) at the United Nations regarding Kashmir. Those were days when the Jhelum River had turned red and there was a high probability indeed that the UN file might be reopened.

Rao instructed us that someone from the MEA should visit L K Advani and take him into confidence on the profound calculations necessitating one-on-one meetings with the Iranian leaders at the highest level, lest the BJP create a ruckus in Parliament against his minority government. But in the event, the 15-minute slot allotted to me by the veteran Opposition leader in his modest Pandara Park apartment overran to nearly an hour, as Advani began digging deeper to demand a whole lot of explanations from me.

Well, after listening attentively, he stood up to say something like this with the characteristic twinkle in the eye, ‘What you people are doing is in national interests and you may convey to PM that I am supportive, although we may make some critical remarks.’ Unsurprisingly, Foreign Secretary J N Dixit instructed that I should not keep any record of that meeting.

That was the wonder that was India.

(M K Bhadrakumar is a former diplomat.)

Disclaimer: The views expressed above are the author's own. They do not necessarily reflect the views of DH.