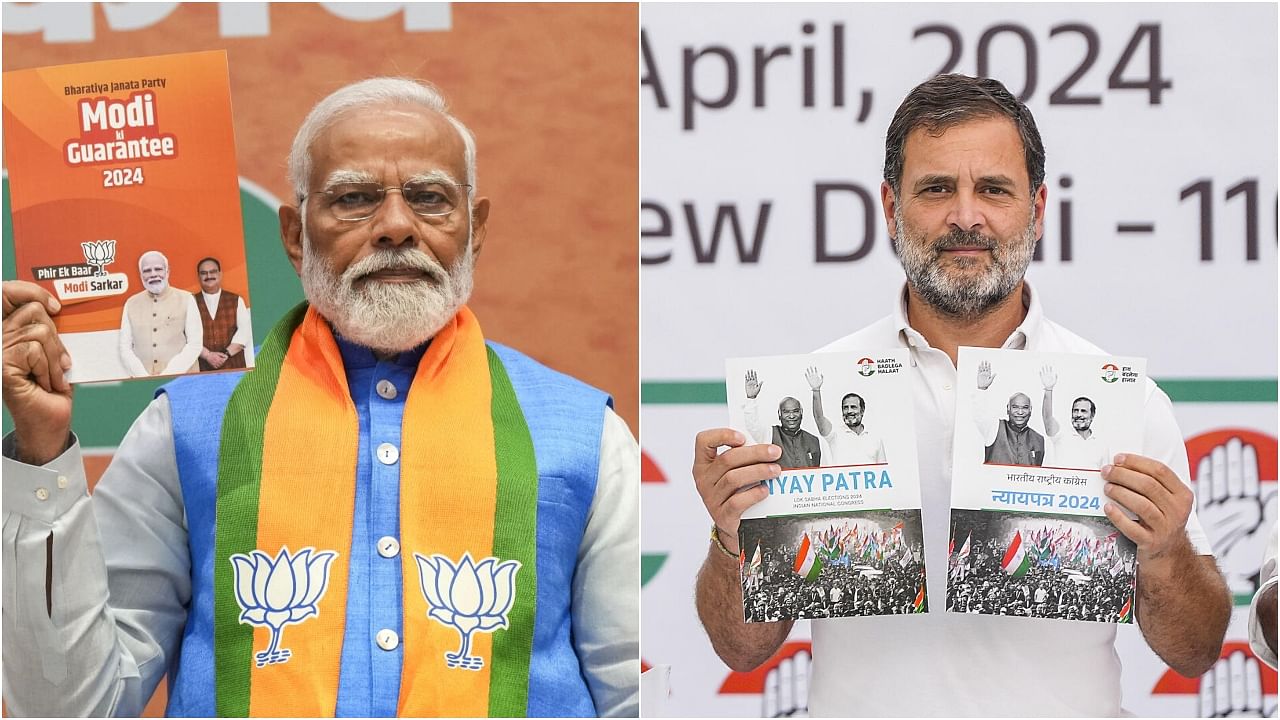

PM Narendra Modi with BJP's poll manifesto (L) and (R) Rahul Gandhi poses with the Congress manifesto for Lok Sabha polls.

Credit: PTI File Photos

The feverish preparations for the 2024 Lok Sabha elections with hectic campaigning, social media outreach, and organised contact with voters, boils down to a deal between the voter and the candidate — a candidate who mostly represents one of many political parties in India’s crowded and intensely competitive elections. Pressing the button on the electronic voting machine (EVM) is an act of faith, because, all that the voter has in exchange is a promissory note, an IOU of what the next five years will give them as listed in a party manifesto.

Manifestos are written to inform voters. In India, voters tend not to read party manifestos. As a civilisation with an oral tradition, voters listen to speeches, which then become the manifesto of the leader and his party.

This election, the manifestos of the two principal contenders, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the Congress, have been weaponised. In a bizarre interpretation of the 2024 Congress manifesto promise of “welfare of the poor will be the first charge on all government resources”, campaigning in Rajasthan’s Banswara, Prime Minister Narendra Modi said "The Congress manifesto says they will calculate the gold with mothers and sisters, get information about it and then distribute that property. “ He spiced it up adding “This urban-naxal mindset, my mothers and sisters, they will not even leave your 'Mangalsutra'. They can go to that level.”

All is not fair in the war of words that political campaigns wage against their competitors. The specific reference to Muslims as the prime beneficiaries in distributive justice of the gold, mangalsutras from women is not just a misreading of the manifesto it is a distortion of former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh’s commitment that the Muslim minority “must share equitably” in India’s development for which “they must have the first claim on our resources.” By adding a religious and communal spin to the intentions outlined in the Congress manifesto and Singh’s statement, Modi has opened himself up to attack by the Congress for delivering a ‘hate speech’.

The intensity of the confrontation will doubtless escalate, as the BJP’s discourse shifts from visions of building a wealthy India to the viciousness of social polarisation.

In speeches and a manifesto, the ruling regime is expected to render up an account of what has been achieved and what will be achieved till the next election comes around in five years. Since elections are about choosing the side that the largest number of voters think will most probably meet their expectations from the government — which primarily is an increase in well-being and a better quality of life — poll promises tend to be down-to-earth lists.

When a manifesto is marketed as a leader’s guarantee, as in the ‘Modi ki Guarantee’ or as the Congress hawked its pruned list of guarantees to voters in Karnataka, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, and Chhattisgarh in 2023, the document becomes more than a list of what a regime has done and how a government will function.

As the challenger, the manifestos of the Congress and the manifestos of the partners of the Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance (I.N.D.I.A.) are as important, separately and collectively, as the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)’s manifesto. The otherwise chaotic I.N.D.I.A. looks remarkably unified in the targets the parties have separately identified as priorities for governance in the next five years. Common to them all are specific promises: cancelling the controversial Citizenship Amendment Act and Rules, holding the all India Census, increasing direct cash transfers for women and unemployed youth, creating employment, filling vacancies, increasing public spending and legislating a minimum support price (MSP) for farmers. There are other promises too, on holding a caste census and job reservation for women and in the private sector that some parties have made while others are noncommittal.

The Congress’ manifesto has greater significance as it is the principal challenger to the BJP. Its proposals and promises read like a counter-narrative, a road map with specified milestones and a schedule. The 25 guarantees of the Congress reflect the issues that the party and its I.N.D.I.A. bloc partners have identified as the biggest failures of the Modi regime in its 10 years in power. The Mangalsutra-Muslims and women spin by Modi has diverted voter attention from the Congress alternative into the familiar channels of communal polarisation.

In contrast, the BJP’s manifesto is less specific; it has split its schedule for getting things done in two ways. There is a 100-day timeline and then a timeline that extends into a distant and, therefore, unforeseeable future. As the defending champion for the title of ruling regime for the next five years, Prime Minister Narendra Modi is on record that work has already begun on an action plan for the first 100 days.

The second timeline is complicated; if elected for the third term, the Modi government promises to ‘seek’ getting India accepted as the host for the 2036 Olympic Games. It also promises that India will reach the ‘Viksit’ or fully developed economy stage by 2047. Since the usual term of an elected government is five years, the pledge to make India fully developed is intriguing.

A 100-day schedule is not a road map for five years; it is certainly not a plan for taking the Indian economy to the top in the next 23 years. After serving 10 years in office, it is strange that the prime minister feels compelled to announce that there will be a short-term action plan. The plan is to get to Viksit Bharat by 2047; the road map is currently under preparation, therefore, the specifics are unknown.

Neither the BJP nor Modi are new to running the government. If the BJP and Modi were new to running the government, a stop-gap measure like a 100-day action plan would make sense. After 10 years in power, it is inefficient and disappointing.

Political parties expecting to run governments in India know what needs to be done. So does the voter. The manifestos are a list of priorities. If a manifesto has two sets of timelines — 100 days and 23 years — how can voters decide on what is best for them in the next five years?

Shikha Mukerjee Is a Kolkata-based senior journalist.

Disclaimer: The views expressed above are the author's own. They do not necessarily reflect the views of DH.